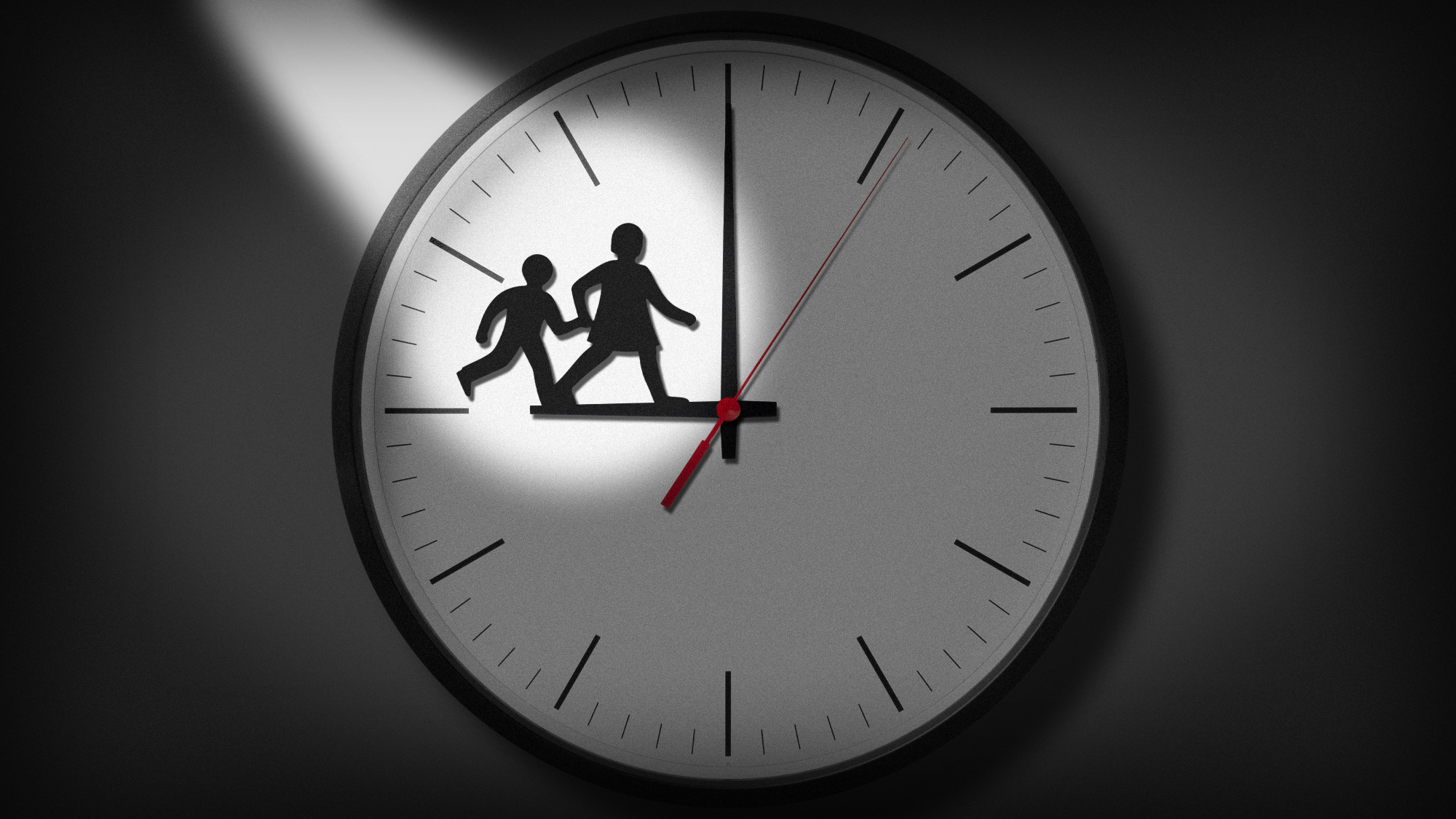

Do youth curfews work?

Banning unaccompanied children from towns and cities is popular with some voters but is contentious politically

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Several southern French cities are imposing night-time curfews on unaccompanied children to reduce youth violence.

The right-wing mayor of Béziers this week banned any unsupervised under-13s on the streets of three districts between 11pm and 6am. Robert Ménard said his move was a response to the "increasing number of young minors left to their own devices" and a rise in "urban violence" – although, as The Independent pointed out, the mayor provided no figures to support this.

Similar curfews have been imposed in other French towns and cities including Nice, and in the most crime-ridden areas of the French-governed Caribbean archipelago, Guadeloupe. Many towns in the Northern Territory of Australia are also considering such measures, after authorities in Alice Springs introduced a two-week curfew following "unprecedented unrest" last month, said ABC News.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But civic leaders and legal experts across the world are divided on the merits of a curfew, and "how it would actually play out".

What did the commentators say?

Emmanuel Macron's centrist government has "hardened its stance on youth violence", said The Times, to try to avert a "humiliating defeat" by Marine Le Pen's right-wing National Rally in European Parliament elections in June. Many left-wing French politicians and human rights advocates oppose curfews, but the right is "convinced" that the measures work.

France does have a problem with young people, said Jonathan Miller in The Spectator. "Grim housing estates" that surround most French cities are "infested with drugs, gangs and unemployment", wrote Miller, author of the book "France: a Nation on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown". But right-wing mayors are "desperately" resorting to curfews. Enforcement "seems likely to be problematic". Who will be accompanying these youths? Will young people respect the curfew? And are they even the main problem?

Last year in France, under-13s accounted for only 2% of those accused of attacking people, compared with 36% aged 30 to 44, according to the Ministry of the Interior.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Béziers curfew is "an experiment", said Ménard. But a similar curfew that he imposed in 2014 was overruled by a court because he failed to prove the existence of particular risks relating to children under 13.

In the US, old curfew laws in more than 400 towns "have long gone unenforced", said The Economist. But last year, many US cities – including Birmingham, Chicago and New Orleans – began "tightening their grip", while others introduced new measures.

There is, however, "little evidence that curfews curtail crime". A meta-analysis by the Campbell Collaboration research network in 2016 found that curfews do not reduce crime, or juvenile victimisation.

In fact, during curfew hours, with fewer people on the street, crime "flourished", said The Economist. Curfews also "unduly penalise" parents who work night shifts, while shutting children inside could increase the risk of abuse.

Youth curfews don't keep "the neglected, the peer-pressured, the ain't-got-nothing-to-lose kids off the street", said Theresa Vargas in The Washington Post. But they do "increase tensions between law enforcement and young people" – especially young people of colour, because by nature, curfews "involve profiling".

They also don't tackle the causes of children being out at night to commit crime, said Aboriginal Legal Service director Peter Collins. Many poorer homes are "dilapidated and overcrowded". There is often drunkenness, mental illness or serious violence, and an absence of caregivers.

"All of these issues are a product of the chronic, long-standing Aboriginal disadvantage and marginalisation" in Australia, he said. Curfews do nothing to tackle them, but are "emblematic of a government which is bereft of ideas".

What next?

Curfews are "more symbolic than effective", said Miller. They are popular with voters – 67% of French people believe a curfew should be introduced for minors all over the country, according to a recent poll.

But while curfews may make politicians look tough on crime, enforcing them could even "distract police from more pressing matters", said The Economist.

Ultimately, they should be treated as a short-term solution, a "circuit breaker", Rick Sarre, a law and criminal justice professor at the University of South Australia, told ABC News.

But look at the evidence, Alain Bauer, a professor of criminology, told The Times. If violence in the streets dies down after curfews are introduced then, logically, "they can be considered successful".

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?Today’s Big Question There could be more to the story than politics

-

Demands for accountability mount in Alex Pretti killing

Demands for accountability mount in Alex Pretti killingSpeed Read Pretti was shot numerous times by an ICE agent in Minneapolis

-

FBI bars Minnesota from ICE killing investigation

FBI bars Minnesota from ICE killing investigationSpeed Read The FBI had initially agreed to work with local officials

-

ICE kills woman during Minneapolis protest

ICE kills woman during Minneapolis protestSpeed Read The 37-year-old woman appeared to be driving away when she was shot

-

Campus security is under scrutiny again after the Brown shooting

Campus security is under scrutiny again after the Brown shootingTalking Points Questions surround a federal law called the Clery Act

-

How the Bondi massacre unfolded

How the Bondi massacre unfoldedIn Depth Deadly terrorist attack during Hanukkah celebration in Sydney prompts review of Australia’s gun control laws and reckoning over global rise in antisemitism

-

Who is fuelling the flames of antisemitism in Australia?

Who is fuelling the flames of antisemitism in Australia?Today’s Big Question Deadly Bondi Beach attack the result of ‘permissive environment’ where warning signs were ‘too often left unchecked’

-

Executions are on the rise in the US after years of decline

Executions are on the rise in the US after years of declineThe Explainer This year has brought the highest number of executions in a decade