The birth of impressionism

Now iconic, the style of art characterised by airy colors and undefined brushstrokes was criticised in its early days

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The 15 April 1874 has a good claim to be the founding moment of modern art. A group of 31 artists, who'd often been rejected by the official Paris Salon, had decided to stage their own show at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, a photographers' studio. They included Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley, all of whom were regarded as part of the "avant-garde" (a military term that had only recently acquired its modern meaning). The show had some 3,500 paying visitors (400,000 visited the Salon) and it made a loss. Most of the reviews were negative. But it launched impressionism as a movement.

How did it get the name "impressionism"?

The word wasn't coined by the artists (they billed themselves as the "Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers, etc"). It was originally a term of abuse. The journalist Louis Leroy wrote a review in Le Charivari – a 19th century French equivalent of Private Eye – mocking the exhibition. "An impression indeed!" he wrote of Monet's Impression, Sunrise (1872). "Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape." By the established standards of the day, Monet's painting of the Le Havre docks at sunrise was less a painting than an oil sketch. Leroy's sneering label, though, captured the snapshot-like quality of impressionist works – the emphasis on the way light and colour hit the eye. These seemed shocking to critics at the time: Le Figaro called the show "a frightful spectacle of human vanity straying into dementia".

Why was the art felt to be so novel and shocking?

For most of the 19th century, the French art world was dominated by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, a national institution that saw painting as a science, and promoted a rigid hierarchy of techniques and genres. Precise perspective, careful drawing, theatrical lighting effects, smoothly mixed colours and invisible brushwork were the hallmarks of what's now known, disparagingly, as "academic art". Large-scale depictions of scenes from history and classical literature were seen as the highest form of painting. Landscapes, still lifes and scenes from everyday life – the impressionists' specialities – ranked much lower. As a result, their work struck critics as flouting the rules on every front. Their seemingly unfinished daubs, with lowstatus subject matter, added up to "a war on beauty", one wrote.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Did the critics matter?

Critical standards did: the Académie's jurors dictated who gained entry to the annual Salon, which could make or break careers. "In Paris there are scarcely 15 art lovers capable of liking a painter who doesn't show at the Salon," Renoir complained – and that greatly affected sales. But the old system was creaking. Complaints about their conservative tastes had been mounting; the jurors also exercised political censorship, especially during the reign of Napoleon III (1852- 1870). There had been protests in 1863 when the Salon rejected two-thirds of the works submitted, including paintings by Édouard Manet and Pissarro. Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863) was the centrepiece of a "Salon des Refusés" that year. Manet later became the elder statesman of the impressionists.

Did impressionism change the rules?

Not in the short term. Even when the impressionists' paintings began to sell, the Académie's values still affected prices. In the 1870s, you could buy a landscape by Cézanne for a fraction of the price of a ballet dancer by Degas, because paintings of figures came higher in the official hierarchy. It took another 20 years for the impressionists' prices to reach the level of Académieapproved art. By then, though, opinion was turning decisively in their favour. Their optimistic, light-filled paintings were popular; there were seven subsequent shows. "The public is cheerful, people have a good time with us," the painter Gustave Caillebotte reported during the successful fourth impressionist exhibition in 1879. They were promoted by influential admirers, such as the novelist Émile Zola, a schoolfriend of Cézanne's. Monet and Renoir became rich, famous and respected all over Europe.

What made the impressionists "modern"?

They answered the poet Charles Baudelaire's call for an "art of modern life". They painted images of the modern city, middleclass pastimes and industrial landscapes. Academic painting emphasised idealisation and polish; the impressionists valued freedom of technique, a personal rather than a conventional approach to subject matter, and the truthful reproduction of nature. Impressionism also depended on modern technologies: its signature move – painting outdoors, in natural light, instead of in a studio – was possible thanks to the invention, mid-century, of premixed paint in portable tubes. And it was, in part, a reaction to photography. Illustrative, realistic painting, as promoted by the Académie, couldn't compete with photos. Paintings concerned with subjective perception could.

What is their legacy?

By the mid-1880s, the impressionists began to dissolve, as several of the group went in different directions. Impressionism provided a technical starting point for many successive modern art movements – starting, obviously, with the postimpressionism of Degas, Cézanne, Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, but spreading further afield. When Wassily Kandinsky saw a Monet haystack for the first time in Moscow in the 1890s, he began to conceive of abstraction: "objects were discredited as an essential element", he noted with excitement. Many US abstract expressionists acknowledged their impressionist precursors. This legacy is being celebrated in France this year with a blockbuster exhibition at the Musée d'Orsay, and with events in Normandy, Bordeaux and elsewhere.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Quiet divorce is sneaking up on older couples

Quiet divorce is sneaking up on older couplesThe explainer Checking out; not blowing up

-

Admin night: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a party

Admin night: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a partyThe Explainer Grab your friends and make a night of tackling the most boring tasks

-

7 hotels known for impeccable service

7 hotels known for impeccable serviceThe Week Recommends Your wish is their command

-

More than a zipper: Young Black men embrace the ‘quarter-zip movement’

More than a zipper: Young Black men embrace the ‘quarter-zip movement’The Explainer More than a zipper: Young Black men embrace the ‘quarter-zip movement‘

-

David Hockney at Annely Juda: an ‘eye-popping’ exhibition

David Hockney at Annely Juda: an ‘eye-popping’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends ‘Some Very, Very, Very New Paintings Not Yet Shown in Paris’ testifies to the artist’s ‘extraordinary vitality’ and ‘childlike curiosity’

-

Broadway actors and musicians are on the brink of a strike

Broadway actors and musicians are on the brink of a strikeThe explainer The show, it turns out, may not go on

-

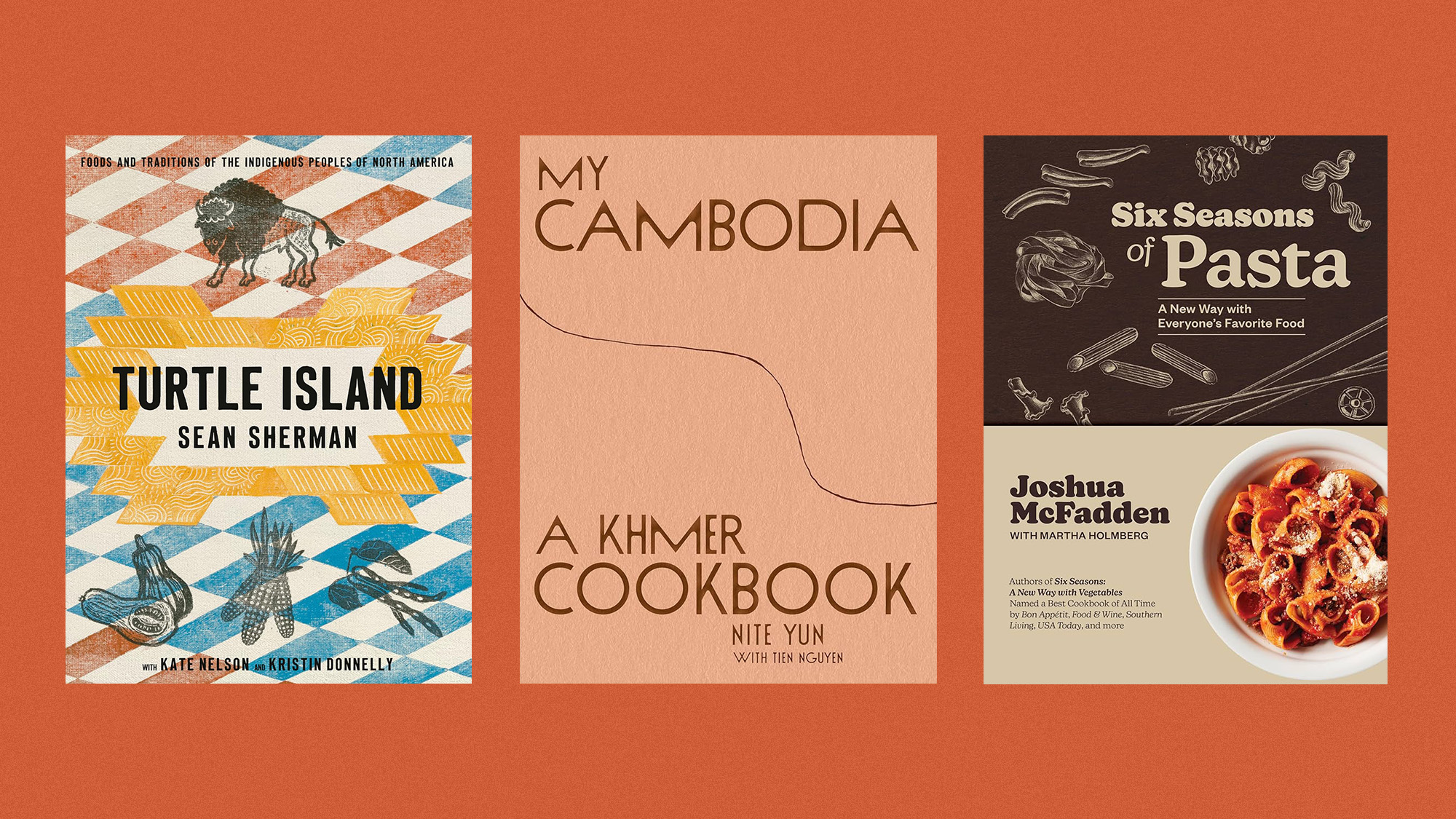

Projects and pantry staples: Fall’s new cookbooks are primed to help you achieve all sorts of deliciousness

Projects and pantry staples: Fall’s new cookbooks are primed to help you achieve all sorts of deliciousnessThe Week Recommends Starring new releases from celebri-cooks Samin Nosrat and Alison Roman

-

Trouble on the seas as cruise ship crime rates rise

Trouble on the seas as cruise ship crime rates riseThe Explainer Crimes on ships reached nearly a two-year high in 2025