Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious – an 'enchanting' show

Exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery shines spotlight on artist whose reputation was eclipsed by her husband

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tirzah Garwood is an artist who has been ill-served by posterity, said Laura Freeman in The Times. Although a highly accomplished draughtsman and engraver in her own right, she is invariably remembered as "Mrs Eric Ravilious": Garwood (1908-1951), who married the great painter of interwar England in 1930, saw her reputation eclipsed by that of her husband even before his "hero's death" in 1942, when he was lost in a seaplane over the Arctic. And while Ravilious's posthumous fame has never diminished, Garwood, who died from cancer aged just 42, has been all but forgotten.

Now, at long last, a new exhibition has put her in the spotlight. Bringing together more than 80 of her works, it reveals her talent for producing scenes of nature and everyday life that were "part Victoriana, part surrealism" – possessed of "a fairy-tale quality" but never "sweet" or "twee". When the Dulwich Picture Gallery mounted a show devoted to Ravilious in 2015, it was "a huge hit". Can this event replicate its success?

Early in her career, Garwood excelled at wood engraving, said Florence Hallett on the i news site. She "mastered" the "notoriously difficult medium" under the tutelage of Ravilious, whom she met when he taught her at Eastbourne School of Art. Her engravings, as seen in her 1929 series "Relations", are full of "humour" and "astutely observed" characters. A "wonderful" picture from the series depicting shoppers on Kensington High Street is a fine bit of social comedy. Garwood's "redoubtable" aunt is seen stepping into the path of a horse, while the "subdued" figure of the artist herself follows meekly. She excelled in other forms, too, creating "odd, unsettling" paintings that distorted scale and viewpoint. "Etna", for instance, has a toy train seemingly traversing a real landscape.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

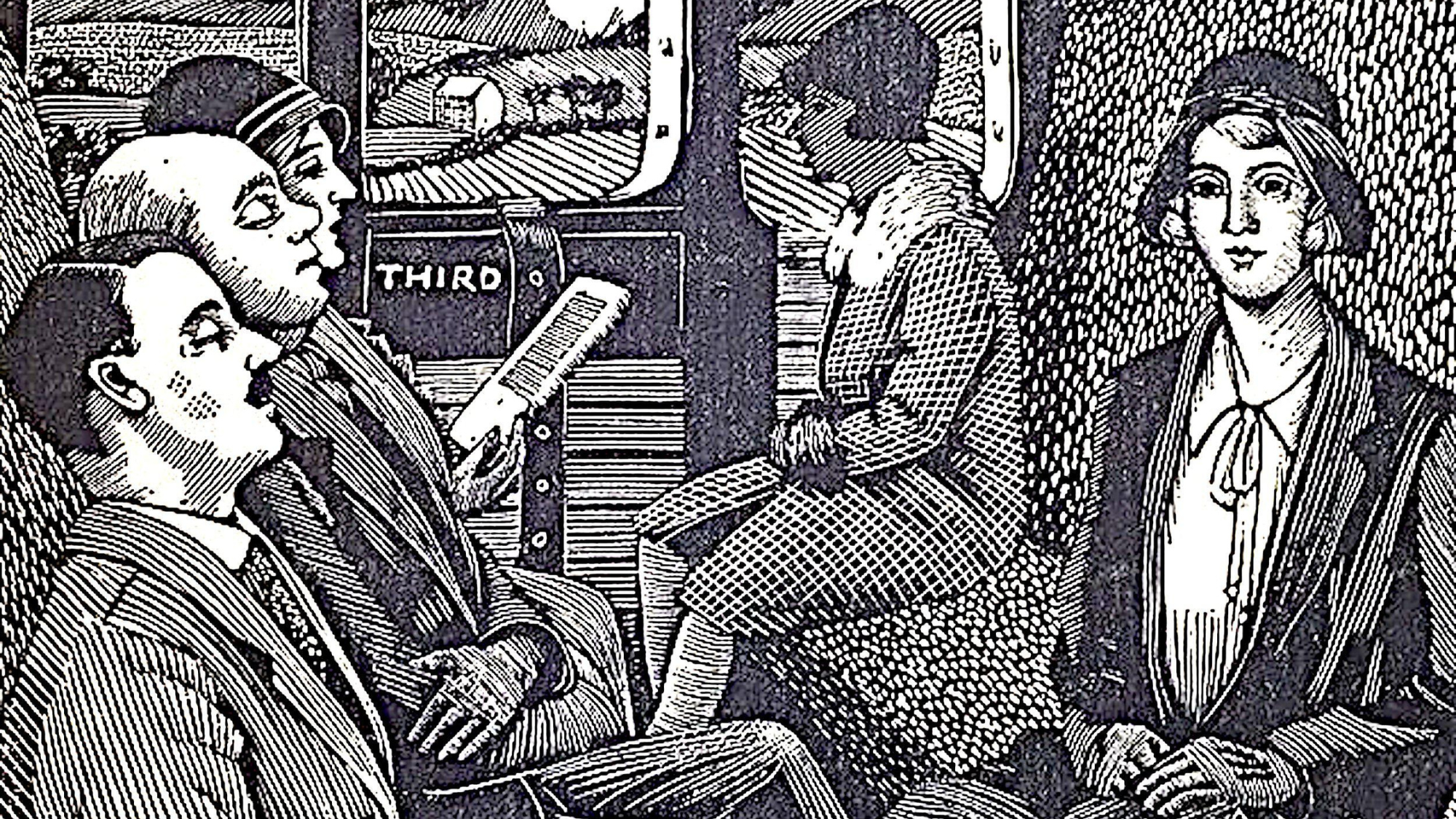

Garwood was truly "original", said Laura Cumming in The Observer. She had "an extraordinary gift for texture and tone", perhaps best demonstrated by a woodcut of the interior of a railway carriage. She captures the "scratchy horsehair seats", "stiff leather gloves" and "the oddly irregular sheen of prewar silk stockings" with remarkable precision. Yet following the birth of her three children, lack of time forced her to turn to less demanding work, not least some unusual and "compelling" models of building facades – "a village shop, a Methodist chapel, a semi-detached house" – boxed inside frames. They are "unique hybrids of mid-century watercolour and doll's house". Her final paintings, produced as she lay dying in a nursing home, are "wild and spry" and "self-reflective": most touching is a painting of a "pale, long-necked" ceramic figure gazing up into a starry sky. If it is in part a self-portrait, it contains "no self-pity". It's a lovely coda to an "enchanting" show that is "a bright surprise from first to last".

Dulwich Picture Gallery, London SE21. Until 26 May

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com