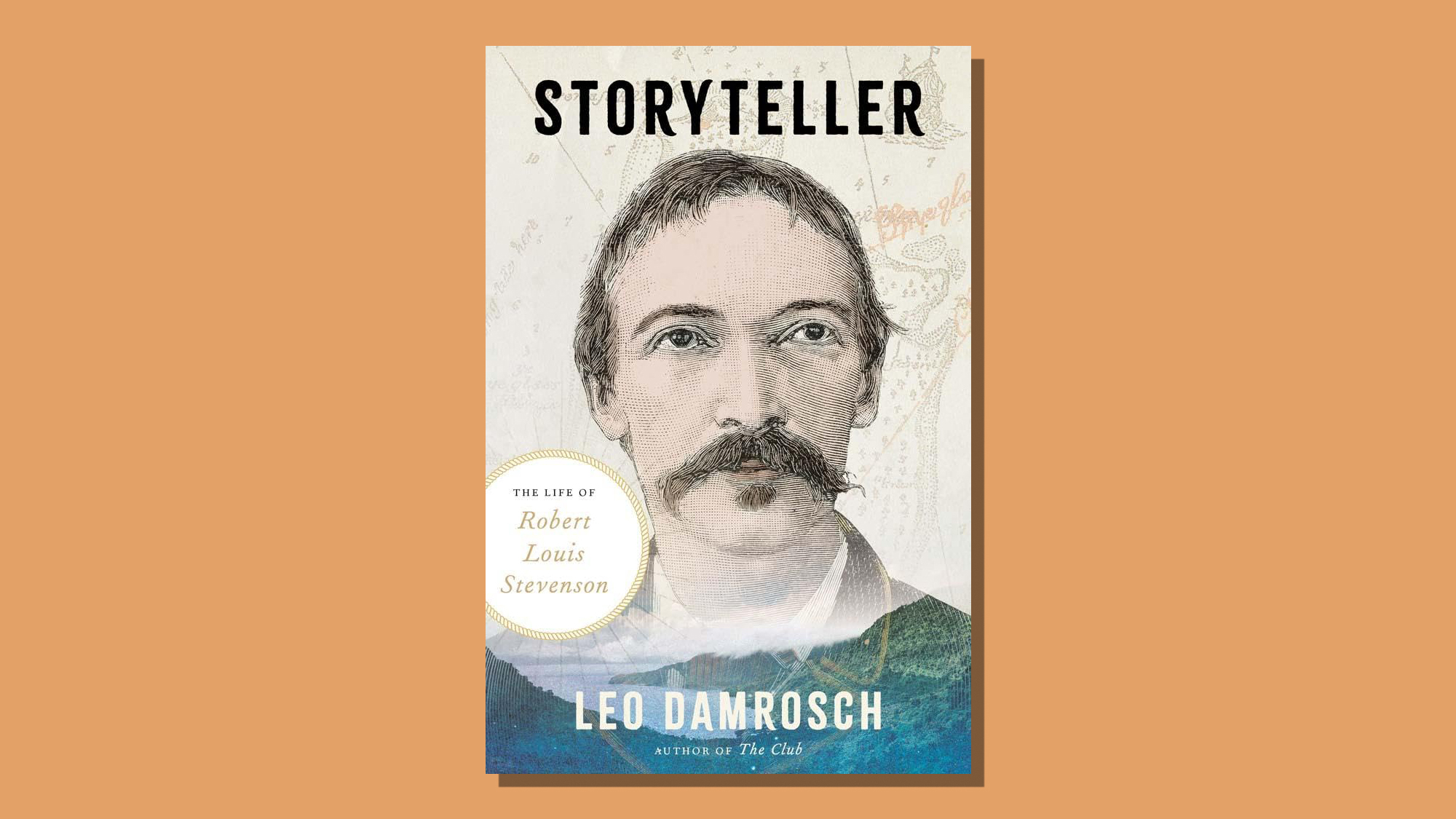

Storyteller: a ‘fitting tribute’ to Robert Louis Stevenson

Leo Damrosch’s ‘valuable’ biography of the man behind Treasure Island

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Since his death, aged 44, in 1894, Robert Louis Stevenson has had a “distinctly mixed” literary reputation, said Andrew Motion in The New Statesman.

To many modernists, and especially the Bloomsbury Group, his adventure-filled novels – among them “Treasure Island”, “Kidnapped” and “Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde” – “looked old hat”. Like Kipling, he has sometimes seemed to be “on the wrong side of history”, and has been dismissed as a mere children’s writer. Yet he hasn’t lacked for heavyweight admirers – Jorge Luis Borges, Vladimir Nabokov, Hilary Mantel – and has remained popular with general readers.

In his “sensible, sympathetic and thorough” biography, the American scholar Leo Damrosch chronicles Stevenson’s “fascinating” life and offers “wise” judgements about his work. “Stevenson was a wonderful man and at his best a great writer”: this “valuable book” captures those qualities.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Born in Edinburgh in 1850, “Stevenson was not supposed to be a writer”, said Meghan Cox Gurdon in The Wall Street Journal. His grandfather and father were civil engineers, responsible for many of Scotland’s earliest lighthouses, and they expected him to enter the family business.

But the “sickly” young man – who was plagued all his life by “bad lungs” – was drawn instead to a bohemian milieu. A “stupendous conversationalist”, who wore “velvet jackets and flamboyant sashes”, Stevenson fitted in easily: he befriended writers such as Edmund Gosse and Henry James (as well as the one-legged poet and editor William Ernest Henley, who helped inspire Long John Silver) and began publishing essays and travel articles. “Much to the grief of his Presbyterian parents”, he also declared himself an atheist.

In 1876, while in France, Stevenson “fell completely” for Fanny Osbourne, an American 10 years his senior with an estranged husband back in California, said David Mills in The Sunday Times. He followed her to America (though the journey “nearly killed him”) and they married in 1880. They settled in Bournemouth, but later moved to America, and “ultimately on to Samoa where, in 1894, Stevenson died of a stroke”.

Although Stevenson is a riveting subject, Damrosch’s ignorance of Britain leads to some errors – as when he claims that “Cockfield in Sussex” lies “40 miles east of Cambridge”. But this is, overall, a “generous and capacious account”, marked by “satisfying touches of offhand laconic wit”, said Margaret Drabble in the TLS. As such, it’s a “fitting tribute” to a “master storyteller”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipe

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipeThe Week Recommends This traditional, rustic dish is a French classic

-

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriors

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriorsThe Week Recommends British Museum show offers a ‘scintillating journey’ through ‘a world of gore, power and artistic beauty’

-

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brand

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brandThe Week Recommends The electric SUV promises a ‘great balance between ride comfort and driving fun’

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ love letter to Lagos

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ love letter to LagosThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria