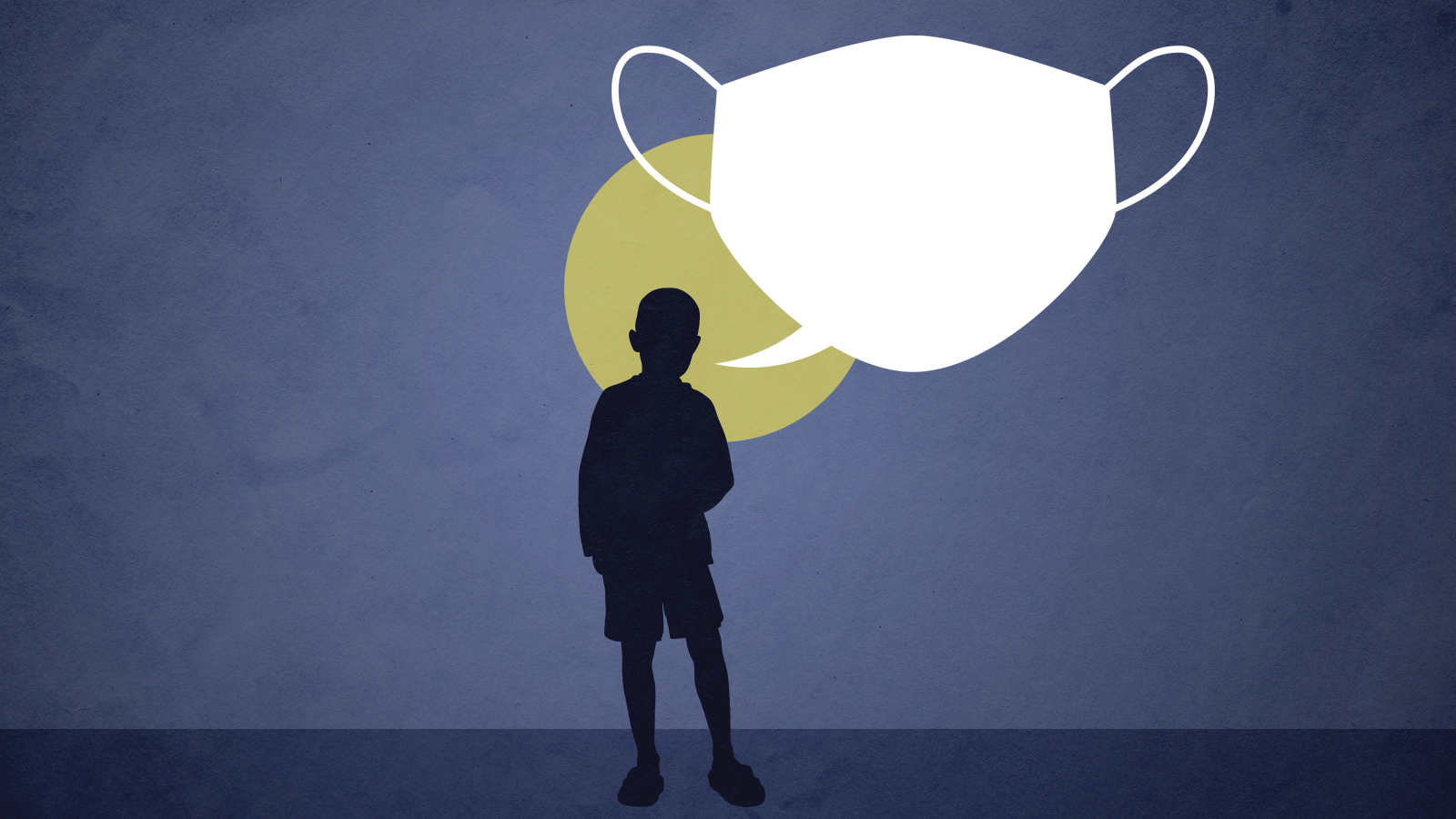

How good sense fell victim to good intentions with mask mandates and speech therapy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I won't use my son's name here, but suffice it to say, it has an R in it. He's had trouble with Rs since he first learned to speak, and at 8-years-old, he still pronounces them as Ws. His Ls are often swallowed, and he has a slight lisp. It's not the end of the world, but he sometimes has to repeat himself three or even four times to be understood, even by me.

My son was making headway on his speech in kindergarten when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. We'd gotten him speech therapy through his public school, and he was being taken out of the classroom once a week for 45 minutes. Progress was meh, but there was some.

COVID-19 put a stop to that, as it did the rest of the world, but my son was luckier than almost any other kid I know. He was back in class by November 2020. He'd pointlessly been doing his speech therapy over Zoom for a month and a half, but then he went back to real people with real lips.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Except he couldn't see them. He was wearing a mask, and so was the therapist.

That's why this Thursday article by The Week contributor Stephanie H. Murray in The Atlantic hit home. I've excerpted it here in part, but the full thing is well worth reading:

[W]hen in-person therapy resumed, masking requirements made it difficult. Some of the dozen-plus speech and language therapists I spoke with said children found the masks distracting. More important, masks hide the mouth from view, which the therapists said is disruptive to some forms of therapy, especially those that target motor speech and motor planning — "anything having to do with actual speech that comes out of your mouth," said Alexandria Zachos, an Illinois-based pathologist. For "that type of therapy, you absolutely need to see the speech therapist's mouth and they need to see yours," Zachos said. [The Atlantic]

My family is fortunate in that my son's pronunciation does, slowly, seem to be improving, but, as Murray notes, speech delays also affect reading and other language skills, like spelling. We're dealing with that now in second grade.

Clearly, this is a case where good sense fell victim to good intentions. And even if the mask mandates end today, nothing will make up for years of lost progress.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jason Fields is a writer, editor, podcaster, and photographer who has worked at Reuters, The New York Times, The Associated Press, and The Washington Post. He hosts the Angry Planet podcast and is the author of the historical mystery "Death in Twilight."