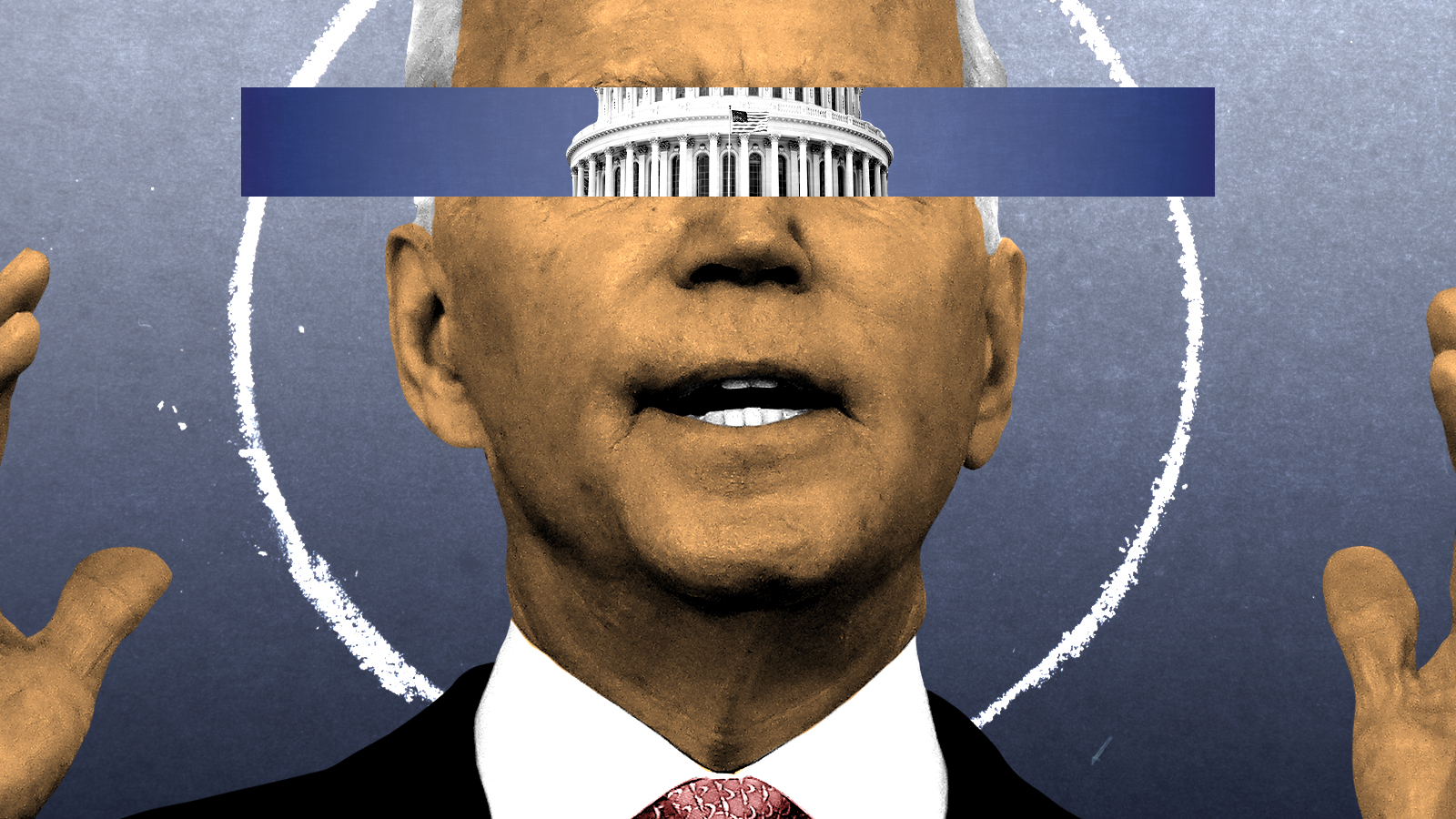

Democrats' problem is Congress itself

Democrats want Congress to operate like a European parliament. It can't happen.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

President Biden's agenda is in trouble.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) told her caucus Monday she would decouple the $1 trillion infrastructure bill already passed by the Senate from more controversial and costly social spending. The same day, Republican senators blocked a bill already passed by the House that would have raised the debt ceiling and provided funding to prevent a government shutdown before December. Democrats could get around that decision by modifying the pending budget resolution, but that would complicate ongoing efforts to reach a bipartisan deal over its other contents. The upshot: The country faces a government shutdown on Friday and unprecedented default on federal debts in October, and Biden seems powerless to help.

Democrats agree this is no way to govern, but the party is fighting over where responsibility lies. Moderates are frustrated with progressives. Progressives are mad at moderates. Backbenchers are angry with the leadership. The leaders blame Republicans. Republicans, meanwhile, can barely conceal their delight. Some analysts are already talking about a failed presidency.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There's plenty of blame to go around, but the real problem lies in the institution of Congress itself. Frustrated by their slim majorities — but with ambitions undiminished — Democrats want Congress to operate like a European parliament in which the majority rules until voters change their minds. Internal rules, constitutional constraints, and geographic polarization make that impossible.

Some of the turmoil we see is theater that satisfies media demands for constant drama. Rather than providing an undistorted glimpse of congressional sausage-making, short-term coverage relies heavily on conventional wisdom, performative quotes, and carefully coordinated leaks. When we find out what really happened in legislative negotiation, it's usually much later and much different from what the public believed at the time. Nearly half a century after the fact, for example, Robert Caro was still able to rewrite the story of President Lyndon Johnson's role in passing civil rights laws.

But the procedural challenges are real, the filibuster included. By raising the threshold for most measures to 60 votes in the Senate, the threat of filibuster promotes arcane procedural maneuvers to ensure bills can pass with simple majorities. Because it can be used only once per fiscal year, this "reconciliation" process encourages the majority party to load up its entire policy wishlist into a single bill. That's one reason Democrats have found it so difficult to settle on the details of their amorphous $3.5 trillion spending package.

Reconciliation also elevates the hitherto obscure Senate parliamentarian into a major player. Last week, for example, Parliamentarian Elizabeth Macdonough ruled Democrats couldn't include immigration reform in their fiscal proposal. Although Democrats complained she was usurping the prerogatives of elected representatives, that may have been a blessing in disguise. With the Biden administration floundering at the border, a vote on de facto amnesty could have further splintered the party and imperiled the bill.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

These challenges to legislation are exacerbated by historically slim majorities. Having dreamt of an FDR- or LBJ-style majority, Democrats don't seem to accept to the reality of an evenly divided Senate and tiny House majority. When every vote is crucial, marginal voters have enormous leverage over the rest of the party. That's why activists frustrated by his opposition to massive social spending are staking out Sen. Joe Manchin's (D-W.Va.) houseboat.

But as much as Democrats might wish otherwise, this tenuous grasp on power is more the rule in Washington than the exception. Filibuster-proof Senate majorities are historically rare, and the rural bias created by equal representation for each state currently favors Republicans (in the past, it benefitted Democrats).

That reality leads some progressives to attack the Senate's very existence, while others prefer to balance their disadvantage with new, presumably Democrat-leaning states in the District of Columbia or Puerto Rico.

Such efforts are wishful thinking. The Constitution explicitly prohibits depriving any state of equal representation without its consent, making abolition of the Senate a fantasy. Adding new states doesn't face that obstacle, but it would require the kind of overwhelming majority Democrats have struggled to win.

Winning a larger majority, in turn, requires the kind of moderate agenda that appeals to swing voters. But the concentration of Democratic support in urban areas of the most populous states makes that difficult. Ensconced in safe seats in blue states, the party's left wing can demand sweeping changes that hold little appeal to centrists in purple states who elect lawmakers like Manchin. Senators from moderate states also have every reason to support the filibuster because it forces party leadership to court their vote for every major bill.

None of this is news to people who work on Capitol Hill, where cold electoral calculation is more important than colorful personalities or ideological consistency. For that reason, it's too soon to write off the Biden agenda as dead on arrival despite its present obstacles, but the significance of success shouldn't be overstated. Democrats still wouldn't have FDR- or LBJ-style power — for one thing, FDR and LBJ never struggled to keep government lights on.

Moreover, even a successful piece of social legislation is compatible with huge losses in the midterm elections. The Biden administration evidently hoped economic recovery, public health improvements, and a clean exit from Afghanistan would buck the historical pattern of the incumbent party losing congressional seats. None of that happened, leaving Democrats with dim prospects for 2022 however the legislative session turns out. And even if Democrats hang onto their majorities, Congress still won't be a European parliament. All the same constraints will remain.

If Democrats have any consolation, it's that Republicans are just as constrained, just as impotent, even in pursuit of their own greatest priorities. That's why we're observing the 10th anniversary of ObamaCare this year.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the deep of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

‘My donation felt like a rejection of the day’s politics’

‘My donation felt like a rejection of the day’s politics’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?Today's Big Question Could political pressure overcome legal obstacles and force either man to give evidence over their relationship with Jeffrey Epstein?

-

Rep. Ilhan Omar attacked with unknown liquid

Rep. Ilhan Omar attacked with unknown liquidSpeed Read This ‘small agitator isn’t going to intimidate me from doing my work’

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help Democrats

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help DemocratsThe Explainer Some Democrats are embracing crasser rhetoric, respectability be damned

-

Can anyone stop Donald Trump?

Can anyone stop Donald Trump?Today's Big Question US president ‘no longer cares what anybody thinks’ so how to counter his global strongman stance?

-

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Schumer is growing bullish on his party’s odds in November — is it typical partisan optimism, or something more?

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency