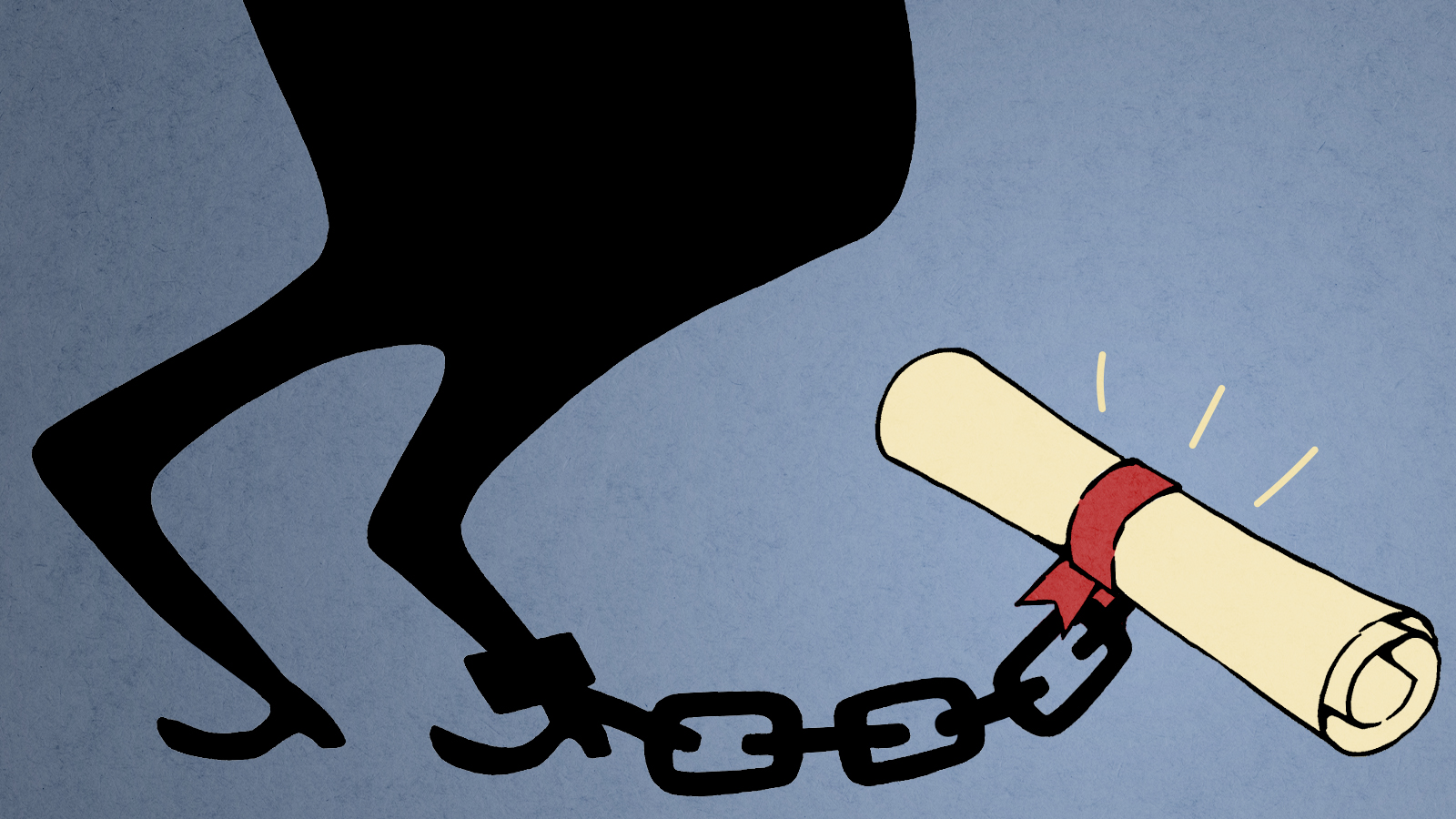

How needless regulations are driving people into student debt and out of work

Lessons in forced schooling from a D.C. daycare provider

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Immigrant Ilumi Sanchez appreciates the value of education. Before coming to the United States in 1995, she earned a law degree in her native Dominican Republic and worked as an attorney.

Her two children also graduated from college, and Sanchez helped support them with income from a home-based daycare she operates in Washington, D.C. Her husband, a doorman, also contributed, and collectively, the family has made education a lifelong priority. Yet Sanchez understands formal education is not the only path to knowledge.

Universities, colleges, and vocational schools serve a purpose, but some occupations can be learned other ways. So Sanchez fought back when Washington passed rules in 2016 requiring daycare providers to earn an associate's degree in early childhood development or a closely related field.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The new regulation, which has not yet taken effect, would force people like Sanchez to go back to school or risk having their businesses shut down. Rather than accept the violation of her right to earn an honest living, Sanchez sued to stop the rollout, and our public interest law firm, the Institute for Justice, represents her.

If Sanchez fails, a degree requirement inevitably would mean fewer daycare providers, and fewer providers would mean higher prices. Washington already has the nation's highest child-care costs. Among other unintended consequences, the mandate would pressure daycare providers to take student loans they cannot always afford — trapping them in debt against their will — to learn skills they do not always need.

Sanchez proves the point. She has worked with children for more than 25 years and already has credentials from a private accrediting agency. More important, her clients love her. If she lacked competence, problems would have surfaced long ago.

Regulators in Washington and beyond don't care. Nationwide, mandatory education requirements have multiplied in recent decades. About one in 20 U.S. workers needed an occupational license to earn income in 1950. Today the rate is about one in four, and many licenses include educational components.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Pennsylvania and Vermont, for example, require college for daycare staff. Florida, Louisiana, Nevada, and Washington, D.C. require college for interior designers. And Georgia attempted to impose a college requirement on lactation consultants until the Institute for Justice fought off the legislation in court on last month.

States also mandate vocational schooling, especially in the beauty industry. Wyoming, Hawaii, New Mexico, and Montana even require African-style hair braiders to earn cosmetology diplomas — though beauty schools rarely teach the skill. Idaho braiders faced the same hurdle until March 28, when lawmakers passed emergency reforms in response to an Institute for Justice lawsuit.

Regulators claim good intentions when they impose these requirements, but the mandates reflect a type of elitism. Many lawmakers and government officials have college degrees. Higher education is part of their identity — a rite of passage — so they assume others need the same experience.

What regulators overlook is the value of diversity. Decisions about education are deeply personal, and one size does not fit all. People should be free to choose for themselves how much schooling they want.

Aspiring chefs, mechanics, artists, musicians, journalists, entrepreneurs, and business managers already have choice. Programs are available for all these pursuits, but enrollment is voluntary. Ironically, not even college professors face government-imposed education requirements. If Sanchez wanted to teach early childhood development and found a college willing to hire her, regulators would have nothing to say.

Coercion never should be part of the equation unless regulators can show the hurdle is necessary and the least restrictive option available to protect public health and safety. Unfortunately, policymakers often act to protect special interests instead. An Institute for Justice report, published Feb. 24, finds that at least 83 percent of requests for new regulations come from occupational and professional associations — that is, lobbyists, not consumers.

This is what happened in Georgia with the decision to force lactation consultants to go to college. The lobbying group behind the law was the U.S. Lactation Consultant Association, which stood to benefit if the law had taken effect, because many of its members' competitors would have been banned from their field.

Mandatory degrees and diplomas rarely make objective sense. In states that take the time to conduct independent reviews, auditors decline to recommend occupational licensing about 80 percent of the time. Forced schooling falls apart under scrutiny.

States widen opportunity gaps when they ignore the evidence. Regulatory regimes often target higher-income fields like medicine and law, but doctors and attorneys have resources to absorb costs. Workers in lower-income occupations do not. Women, minorities, immigrants, former inmates, and other marginalized workers suffer disproportionately.

Going back to school is simply not feasible for Sanchez. She would be nearly 60 by the time she graduates, giving her a small window to repay loans. And passing courses in her non-native English would present challenges.

She believes in education. But formal schooling is not the right answer for everyone.

Daryl James is a writer at the Institute for Justice, where he focuses on economic liberty, property rights, police reform, free speech and educational choice. His articles have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, New York Daily News and dozens of regional and local news outlets across the United States. He enjoys world travel and has visited 25 countries. He currently lives in Taiwan.

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred