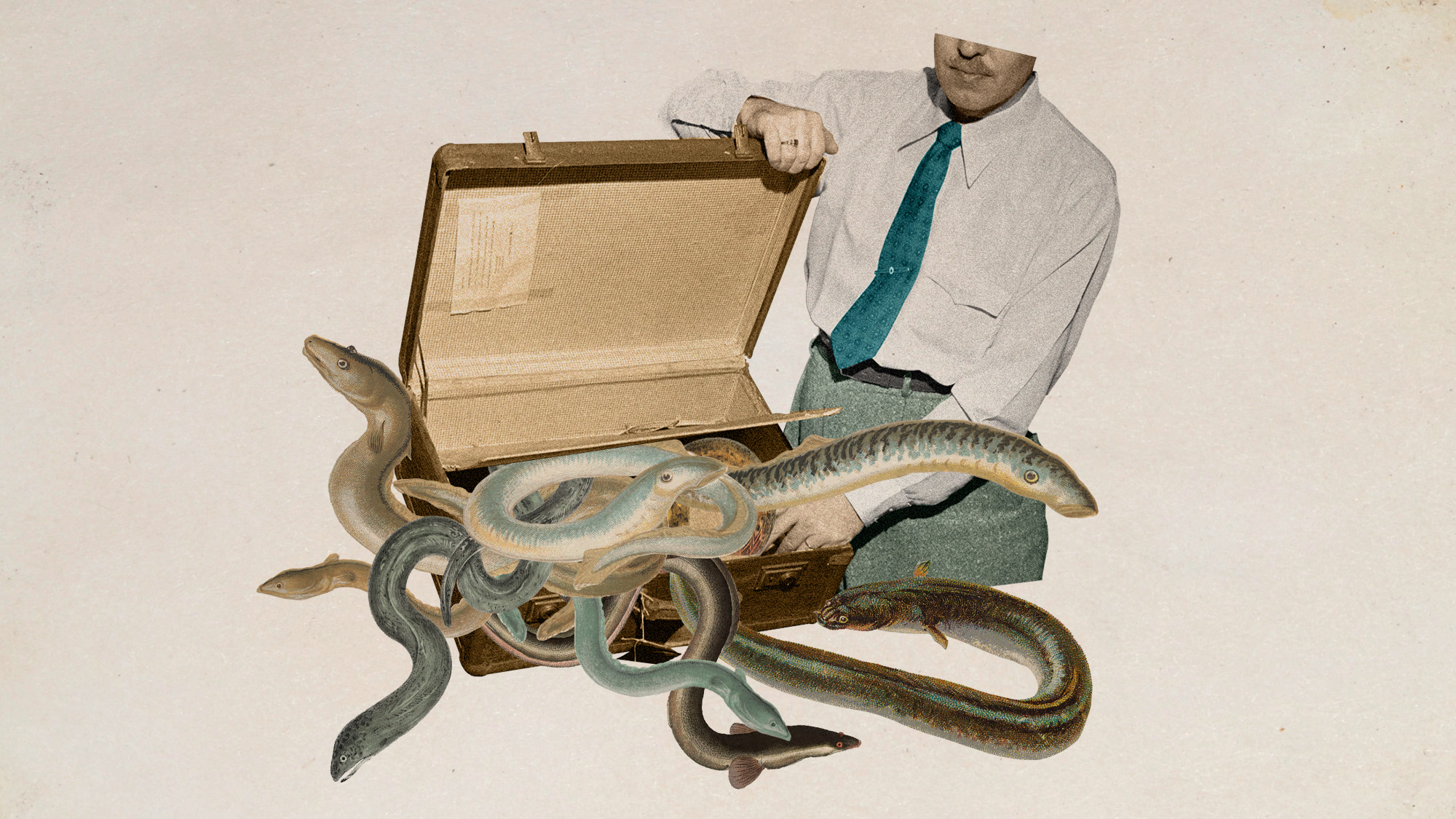

Eel-egal trade: the world’s most lucrative wildlife crime?

Trafficking of juvenile ‘glass’ eels from Europe to Asia generates up to €3bn a year but the species is on the brink of extinction

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Eels have been a staple of European diets for millennia, from London’s jellied eels to Spanish angulas. But the world’s appetite is bringing them to the brink of extinction.

European rivers once teemed with eels; now numbers have collapsed due to overfishing, habitat loss, pollution and climate change. Scarcity, combined with an insatiable demand for the grilled dish, has sent prices soaring and spawned a “thriving illegal trade”, said The Guardian.

Europol recently estimated that up to 100 tonnes of juvenile eels are smuggled from Europe each year, generating €2.5–3 billion in peak years. That makes eel trafficking one of the world’s most lucrative wildlife crimes.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Baby eels: a prized delicacy

“Tiny, translucent and no longer than a finger, juvenile European eels, also known as glass eels, might not look like much,” said Mongabay. But demand for these “slippery creatures” has made them among “the world’s most trafficked animals”.

Adult eels have never been successfully bred in captivity at scale, so farms are “entirely dependent” on wild-caught juveniles to raise to maturity and sell for the table. Glass eels are “a high-value commodity” – especially in China and Japan, the world’s foremost eel consumers.

In the 1990s, after decades of intense overfishing, eel populations around Japan “began to collapse”. Asian farms increasingly turned to wild-caught European juveniles. But every eel taken from the wild causes “lasting ecological consequences”, conservationists say, because the species plays “multiple roles” in ecosystems.

By 2007, the European eel was listed as critically endangered. In response, the EU imposed a zero-export quota, banning trade with countries outside the bloc. Then, “an illegal global market and food fraud developed”, said a 2024 study. The “lucrative market for European eel outside Europe” attracted the attention of criminal organisations, and turned Europe into “the source of the international illegal eel trade”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In 2023, EU authorities seized more than a million live eels in nearly 5,200 operations, almost all destined for Asia.

Future of eel ‘hangs on a hook’

“The future of the eel hangs on a hook,” said Follow the Money. The European eel population has declined by more than 90% since the 1970s.

Between last October and June this year alone, Europol’s Operation Lake, its flagship action against eel trafficking, seized 22 tonnes of glass eels. But despite increasing enforcement, European eels are still “ending up grilled at high-end restaurants as unagi, a prized Japanese delicacy”, said Mongabay. It is a “highly complex, organised crime”, involving smuggling, document fraud, tax evasion and money laundering. Sophisticated criminal networks in Europe and Asia work “in tandem”.

And it’s not just a European crisis: according to a recent study led by Chuo University in Japan, more than 99% of eels consumed worldwide belong to three endangered species: American, Japanese and European.

Even for importers trying to source legal eels, “it is very difficult to determine where these eels originally came from”, Dr Hiromi Shiraishi from Chuo University told The Guardian. Legal variations are exploited by traffickers. European eels are taken to Africa, where they are “cleaned” into legal exports towards Asia. There is “no traceability”. Fish are digitally tracked from fisher to consumer, but there is no such global system for eels. All the while, traffickers “remain one step ahead, their routes as slippery as the fish themselves”.

But soon there will be “an opportunity to reduce this illegal trade”, said Sheldon Jordan and Yves Goulet in The Globe and Mail. In late November, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species will consider the EU’s proposal to enhance the protection of all eel species. At the moment, only the European eel is listed under CITES – but they look so similar that officers “cannot reliably tell them apart” without costly DNA tests. Listing all eel species under CITES would “close loopholes traffickers exploit”.

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?Today’s Big Question Trial will determine if Meta, YouTube designed addictive products

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures

-

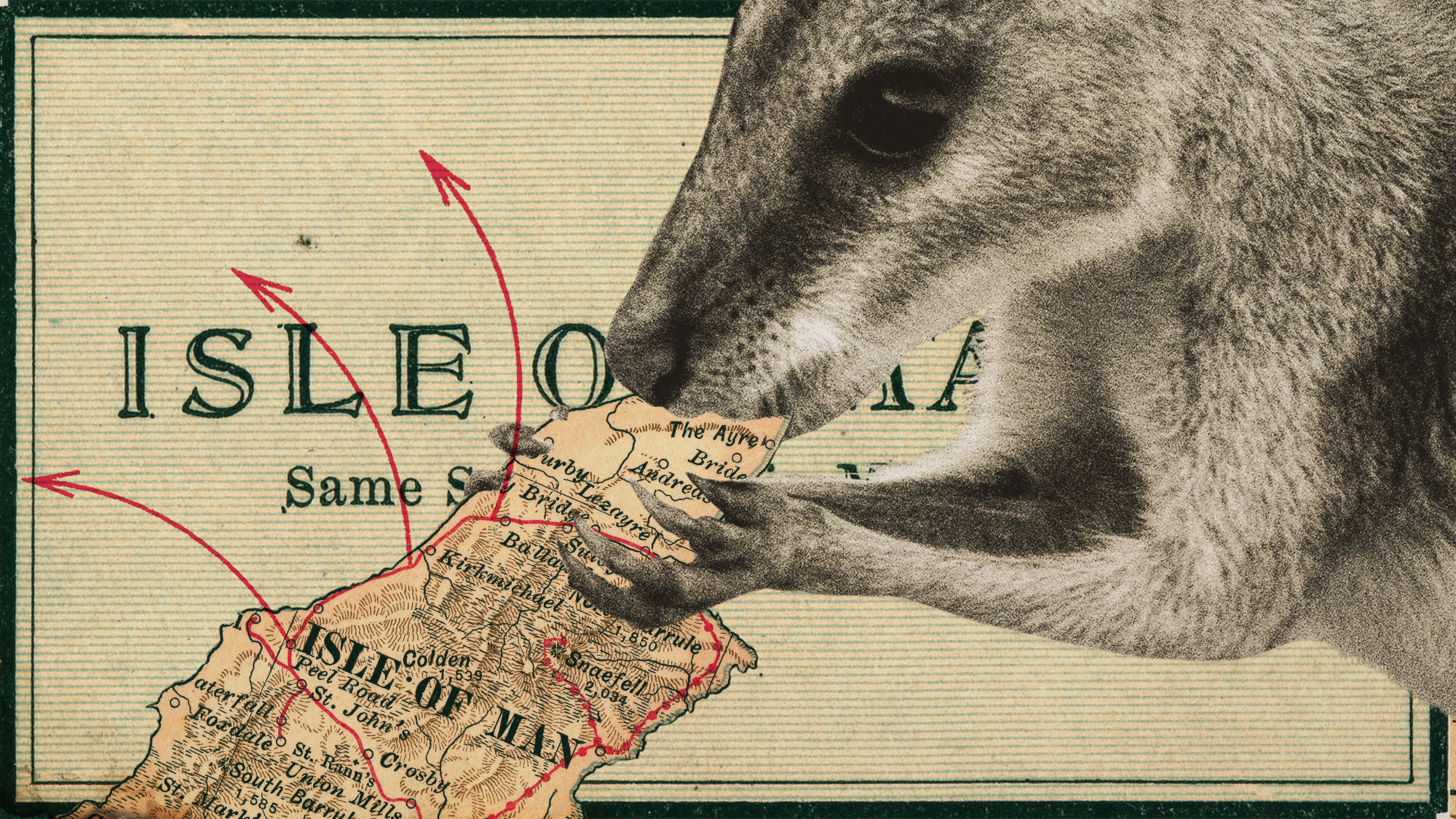

The UK’s surprising ‘wallaby boom’

The UK’s surprising ‘wallaby boom’Under the Radar The Australian marsupial has ‘colonised’ the Isle of Man and is now making regular appearances on the UK mainland

-

Icarus programme – the ‘internet of animals’

Icarus programme – the ‘internet of animals’The Explainer Researchers aim to monitor 100,000 animals worldwide with GPS trackers, using data to understand climate change and help predict disasters and pandemics

-

What do heatwaves mean for Scandinavia?

What do heatwaves mean for Scandinavia?Under the Radar A record-breaking run of sweltering days and tropical nights is changing the way people – and animals – live in typically cool Nordic countries

-

Blue whales have gone silent and it's posing troubling questions

Blue whales have gone silent and it's posing troubling questionsUnder the radar Warming oceans are the answer

-

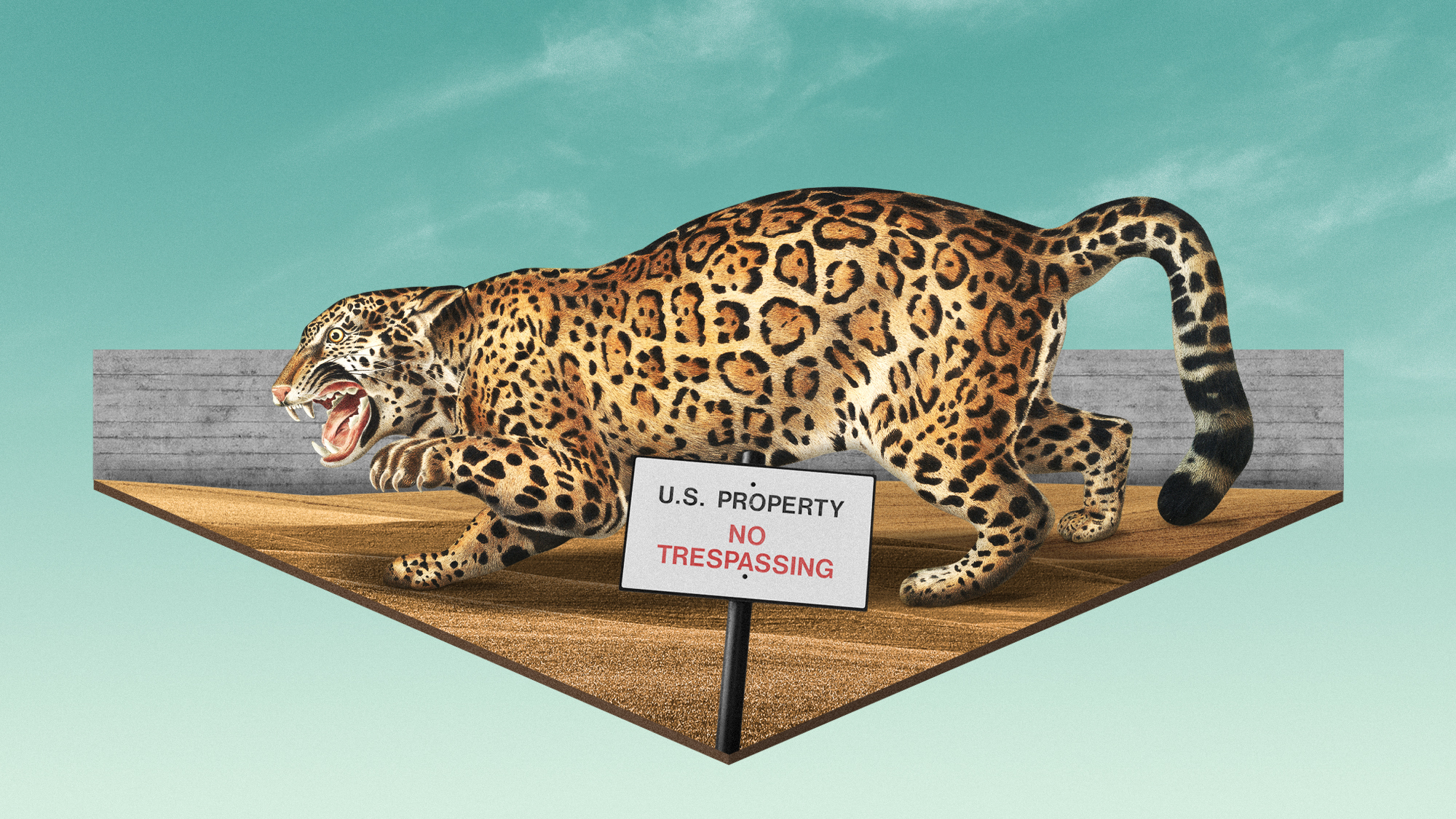

The revived plan for Trump's border wall could cause problems for wildlife

The revived plan for Trump's border wall could cause problems for wildlifeThe Explainer The proposed section of wall would be in a remote stretch of Arizona