A human foot found on Mount Everest is renewing the peak's biggest mystery

The discovery is reviving questions about who may have summited the mountain first

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

More than 340 people have died trying to climb Mount Everest, according to Nepalese officials, so finding human remains on the mountain is not exactly uncommon. However, the discovery of a frozen human foot in early October has brought a partial end to a century-long search — and reignited one of the greatest mountaineering mysteries of all time.

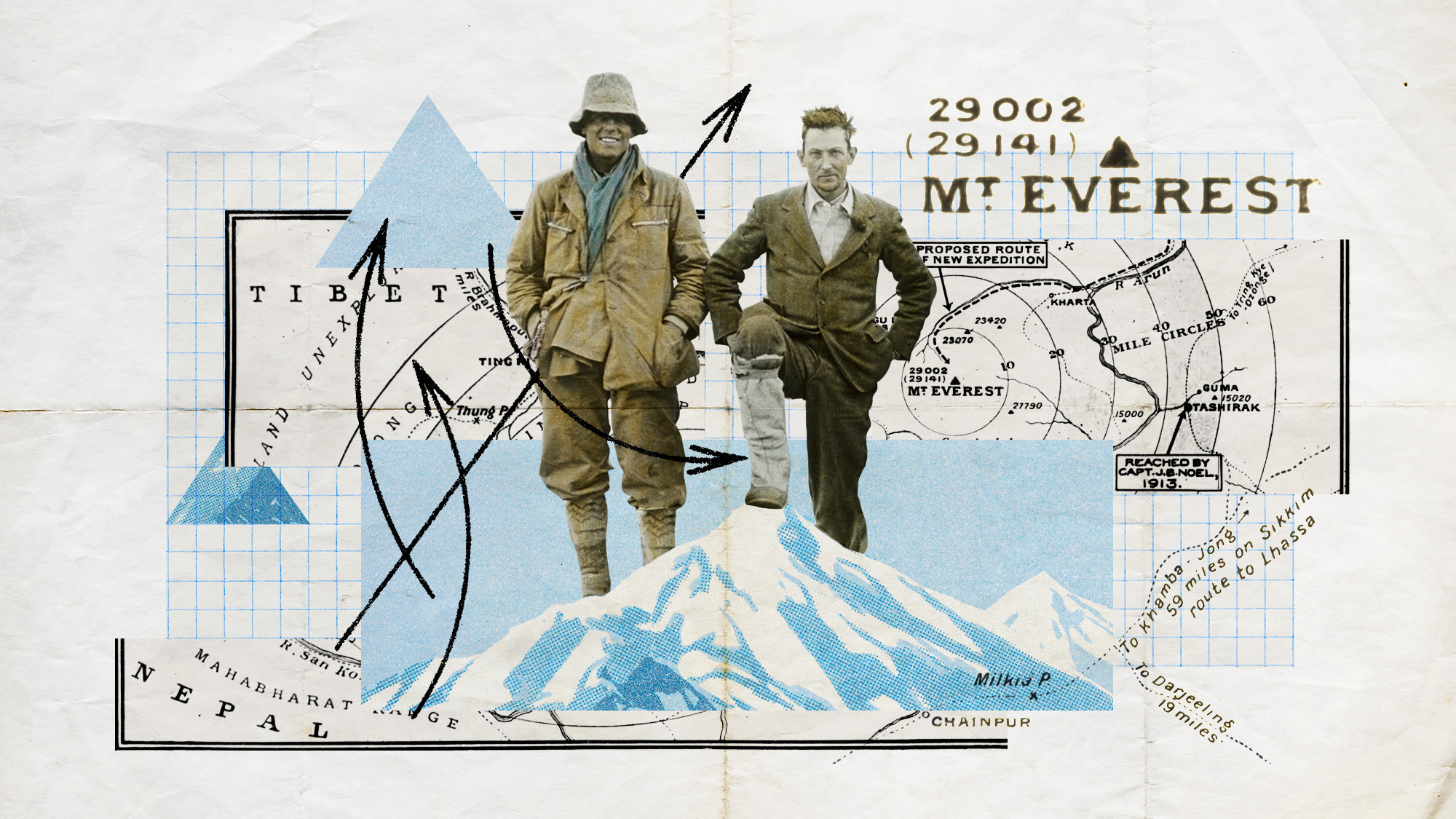

National Geographic reported on Oct. 11 that Everest explorers had found the suspected foot of Andrew "Sandy" Irvine, who disappeared on the mountain alongside his climbing partner, George Mallory, during an expedition in 1924. Mallory's body was found in 1999, but no remains of Irvine had ever been located, until now. The likely discovery of Irvine's foot has people debating one of mountaineering's longstanding questions: Were Irvine and Mallory the first people to ever summit the world's tallest mountain, nearly 30 years before the first confirmed ascent?

What is the crux of this Mount Everest mystery?

It is "not known whether the pair ever reached the summit — an important Everest mystery among climbers and historians alike," said NBC News. This is because any proof that Irvine and Mallory indeed summited Mount Everest in 1924 would change the course of mountaineering history; it would mean the pair conquered the mountain 29 years before New Zealand's Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay made the first confirmed summit in 1953.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The discovery of Mallory's body in 1999 did not provide conclusive evidence that the pair reached the top of Everest, but "historians suspect that a Kodak camera they were carrying may have photographic evidence of a successful summit," said The Washington Post. The discovery of Irvine's foot does not "answer the question of whether Irvine and Mallory made it to the top," Irvine's great-niece Julie Summers said to the Post. But it "should reduce the difficulty of trying to find that Kodak camera," though doing so "remains immensely difficult."

Can this mystery be solved?

DNA testing will be done to ensure that the frozen foot belonged to Irvine. The discovery of the foot "provides an important piece to the longstanding puzzle of what could have possibly happened to the pair and just how close to the mountaintop they reached," said NPR. And filmmaker Jimmy Chin, whose team discovered the remains, is "confident that more artifacts and maybe even the camera are nearby," he said to National Geographic. While nothing is guaranteed, it "certainly reduces the search area."

But even with this newfound information — and hope that the lost camera could contain a picture of Irvine and Mallory at the summit — Irvine's family "has always maintained the mystery, and the story of how far they got and how brave they were, was really what it was about," Summers said to the BBC. And the finding of Irvine's foot "could also raise some new questions: Did he fall off the mountain? How did he become dismembered? Was it before or after his death?"

Beyond Irvine's family, there was another individual who wanted to know the answer to the mystery: the first confirmed man to summit Everest, Edmund Hillary. "I haven't the faintest idea," Hillary said in an early 2000s interview when asked if he thought Irvine and Mallory summited first. It's "one thing to get to the top of a mountain, but it's not really a complete job until you get safely back down to the bottom. I have been the hero of Mount Everest. I'm regarded as such, I've talked as such. So I couldn't really complain too much if, after all this time, I had not been first on top."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures

-

Crest falling: Mount Rainier and 4 other mountains are losing height

Crest falling: Mount Rainier and 4 other mountains are losing heightUnder the radar Its peak elevation is approximately 20 feet lower than it once was