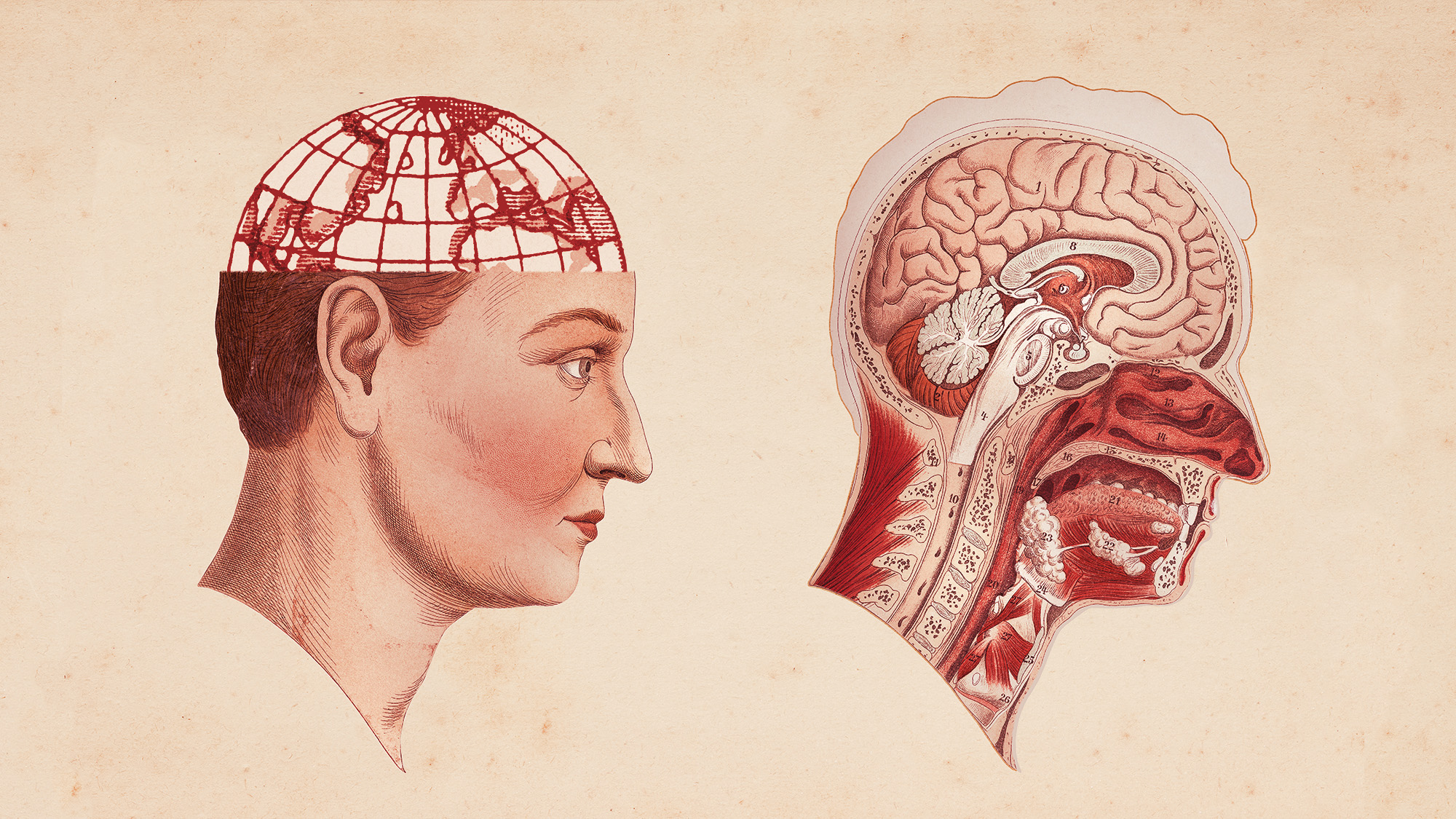

'Nature is heavy' – how climate change affects the brain

Evidence is mounting that mental health and the natural environment are closely linked

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Soaring rates of anxiety, depression, ADHD, PTSD, Alzheimer's and motor neurone disease may be related to rising temperatures and other environmental changes, according to a new book.

The climate crisis has spurred "visceral and tangible transformations in our very brains", wrote Clayton Page Aldern, author of "The Weight of Nature", in The Guardian. As the planet "undergoes dramatic environmental shifts", so too does our "neurological landscape".

'Nature is heavy'

"Fossil-fuel-induced changes" are affecting our brains, "influencing everything from memory and executive function to language, the formation of identity, and even the structure of the brain", wrote Aldern. "The weight of nature is heavy," he said, "and it presses inward."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For example, blue-green algae, which is blooming more often due to climate change, releases a potent neurotoxin that offers "one of the most compelling causal explanations" for the incidence of motor neurone disease, according to Burcin Ikiz, a neuroscientist at the Baszucki Group, a mental health philanthropy organisation.

Aldern also explained that after Superstorm Sandy hit New York in 2012, researchers studied the children of women who were pregnant during the incident. They found that they bear an "inordinately high risk" of psychiatric conditions today because of pre-natal stress.

Boys had 60-fold and 20-fold increased risks of ADHD and conduct disorder, respectively, while girls experienced a 20-fold increase in anxiety and a 30-fold increase in depression compared with girls who were not exposed. They described their findings as "extremely alarming".

Environmental changes due to climate change could lead to alterations in brain development and function, concluded a report by the University of Vienna last year. The researchers were "particularly concerned about the effects of extreme weather events and pollution on cognitive abilities and mental health", said Neuroscience News.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There is also "emerging evidence of associations between poor air quality, both indoors and outdoors, and poor mental health more generally, as well as specific mental disorders", said a study in the British Journal of Psychiatry. It concluded that pollution causes increased cases of depression, anxiety and psychosis.

'In its infancy'

Recognising the connection is not entirely new. Since the 1940s, scientists have known from mouse studies that "changing environmental factors" can "profoundly change the development and plasticity of the brain", said Neuroscience News, and many of the connections between climate and mental health "feel intuitive", said Aldern.

For instance, he pointed out that "when the weather gets a bit muggier, your thinking does the same", and that hotter days can cause "feelings of aggression".

But anxiety about environmental connections creates another bridge. A survey by the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy found that almost three-quarters (73%) of 16- to 24-year-olds reported that the climate crisis was having a negative effect on their mental health.

Our mental health is "so intrinsically tied to everything around us that we constantly see on the news", one youngster told The Guardian last year, adding that they take antidepressants.

Understanding the relationship between mental health and climate remains relatively shallow, said The Guardian, because "as a cohesive effort, the field – which we might call climatological neuroepidemiology – is in its infancy".

Therefore, said the University of Vienna researchers, an intersection of neuroscience and environmental studies would help us "better understand and address these impacts".

Chas Newkey-Burden has been part of The Week Digital team for more than a decade and a journalist for 25 years, starting out on the irreverent football weekly 90 Minutes, before moving to lifestyle magazines Loaded and Attitude. He was a columnist for The Big Issue and landed a world exclusive with David Beckham that became the weekly magazine’s bestselling issue. He now writes regularly for The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, Metro, FourFourTwo and the i new site. He is also the author of a number of non-fiction books.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the deep of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures

-

Environment breakthroughs of 2025

Environment breakthroughs of 2025In Depth Progress was made this year on carbon dioxide tracking, food waste upcycling, sodium batteries, microplastic monitoring and green concrete

-

Crest falling: Mount Rainier and 4 other mountains are losing height

Crest falling: Mount Rainier and 4 other mountains are losing heightUnder the radar Its peak elevation is approximately 20 feet lower than it once was