What I got wrong in 2021

Too much 'coup' quibbling, too little recognition for Liz Cheney's heroism, and more

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's the most wonderful time of the year — that moment I pause in my punditry to reflect on what I've written over the past 12 months, highlighting some of the things I got right, but focusing special attention on what I got wrong.

Writing a column that appears multiple times a week is always challenging, though it's hardest during election years, when there are new polls every few days, plus primaries and debates and conventions to cover, all of them careening by at a million miles an hour, and all of them demanding shrewd analysis and sharp takes. Yet even by that standard, the last two presidential election cycles have been uniquely trying.

The 2016 election gave us the ignoble spectacle of Donald Trump's campaign for president, including two surprise upsets — first Trump's victory in the GOP primaries, and then his shocking defeat of Hillary Clinton. But 2020 was far worse, with the deadliest pandemic in a century serving as the backdrop to the political circus, including the incumbent president falling ill with the disease a little over a month from Election Day, a closer than expected outcome to the vote, and then, of course, the sitting president refusing to accept and flagrantly lying about the results.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

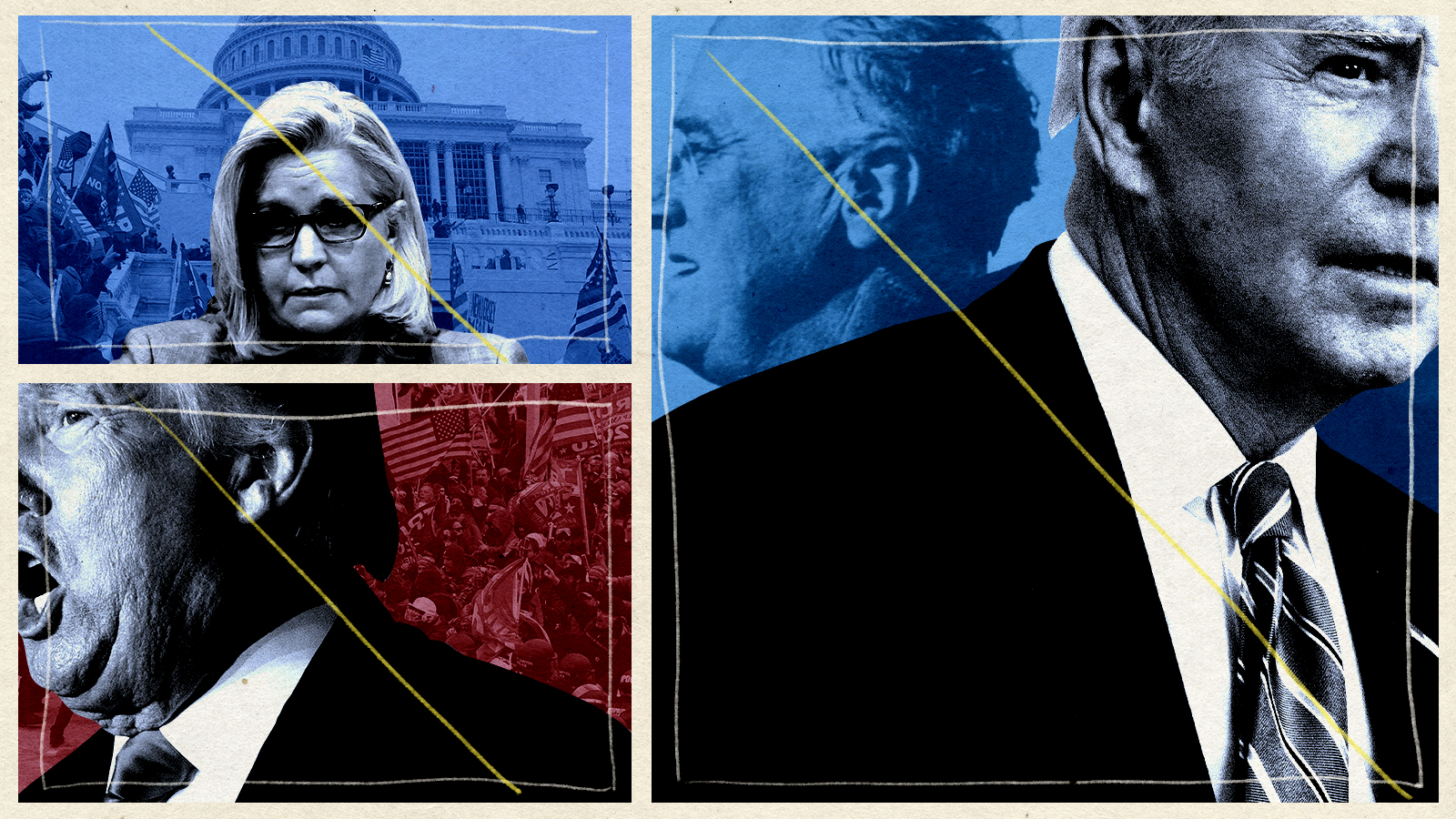

That maelstrom of extraordinary news bled into the opening weeks of 2021, with the insurrectionary violence on Capitol Hill taking place just six days into the new year. I'm proud of most of what I wrote immediately after the uprising and over the surreal two weeks that followed. This included Congress belatedly certifying the results of the election once the building had been secured, the president being banned from social media platforms, Congress impeaching the president for an unprecedented second time, and President Biden's inauguration taking place under quasi-apocalyptic conditions, with overwhelming, militarized security, no public audience, and everyone on the dais wearing medical masks.

What stands out from my writing in this period, and for the months to follow, was how much attention I devoted to the prospect of a second American civil war, a subject I'd written about on multiple occasions over the previous year. That set my writing apart from most other commentators, who tended to view Trump's desperate attempts to remain in office as the leading edge of dictatorship. It's true, of course, that a president who refuses to accept the outcome of a democratic election and seeks to hold onto power is acting from a tyrannical impulse. But I never seriously worried Trump could succeed in his efforts. I did worry, and still do, about such efforts tearing the country apart, with cycles of insurrection on both the right and left inspiring one another, and government efforts to suppress the unrest serving as gasoline to fan the flames of violence.

But that doesn't mean I always got the analysis right. In my first column after Jan. 6, I made a point of rejecting the use of the word "coup" to describe the events Trump had set in motion:

The events of Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2021 were not an attempted coup.Words mean things, and it's extremely important that we get our concepts right. A coup is an elite action, when people near the seat of power (usually senior members of the military) defy the law to overthrow a government and install another in its place. [The Week]

In technical terms, I stand by this. Trump was already president. If he rejected the outcome of an election, and his supporters prevented his successor from taking office, that wouldn't be the overthrow of the government and the installation of a new one backed by force. It would be a rejection of democracy and the transformation the presidency into an authoritarian office backed by a violent insurrection. I also think I was right to assume in this same column that the military would have treated such an act as illegitimate, meaning the power grab likely would have failed.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Yet as time has gone on and we've learned more details about what happened in the days and weeks leading up to Jan. 6 — including the memo from attorney John Eastman laying out how to thwart certification of election results in Congress and the Powerpoint presentation circulated through the White House advocating a national emergency to delay Biden's inauguration — I've come to think that choosing to fight and die on the hill of whether or not Trump and his allies were fomenting a "coup" is a textbook example of missing the forest for the trees.

The highest level of the administration was doing everything it could think of to keep itself in power in defiance of the outcome of a legitimate election, including encouraging an assault on the seat of the national legislature. If that wasn't a coup in the strictest terms, it was undeniably an act that aimed to overturn the democratic character of American government. That's what matters, and semantic debates about precisely what to label it are a trivial distraction.

This shift in the direction of viewing the events of Jan. 6 as even more alarming than they seemed at the time has also led me to regret the way I've responded to Wyoming Republican Rep. Liz Cheney's relentless focus on exposing to all the world the existential threat Trump poses to American democracy and the U.S. Constitution. This is more an error of omission than one of commission. I did write one brief item sniping at her for continuing to stake out positions on foreign policy that I consider reckless and contrary to American interests. But mostly I've ignored her as she's broken ranks from her party to play a lead role in the House investigation into the events of Jan. 6.

That now seems more than a little petty to me — and mainly an expression of intellectual inertia. I left the Republican Party during the administration of George W. Bush, and Cheney is very much an ideological throwback to that era of the GOP. I don't want to return to that era, and I consider the Trump phenomenon a partially understandable reaction to its mistakes. But that shouldn't blind me to the admirable courage Cheney has shown over the past year, or to the reality that the Trumpified Republican Party is orders of magnitude more dangerous to the country than that earlier incarnation.

When it comes to my coverage of Biden's first year in the White House, I regret just one thing, though it's an important one. I began the year by noting that Democrats underperformed in 2020, and that this meant Biden would have to govern moderately. By late spring, I was making the same cautionary point in reference to the administration's ambitious legislative agenda, and by late summer, with the president's approval rating in a free fall that eventually left him as much as ten points under water, it was a regular theme of my writing.

But for a brief period in early April, as Biden proposed the bill that would eventually become the trillion-dollar bipartisan infrastructure package that passed in November and prepared to announce the separate multi-trillion-dollar social spending bill that is still languishing in the Senate, I let down my guard, allowing myself to dream.

Could it be that we were finally seeing a reversal of the Reagan Revolution that had set the parameters of the possible in public policy for the past forty years? Might Biden and his party succeed in finally overthrowing neoliberalism in favor of a third wave of progressive policymaking that would rival the New Deal of the 1930s and Great Society of the 1960s?

I included plenty of hedges in even the rosiest of these columns. But I shouldn't have gone even that far. I knew better. Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson led parties that held supermajorities in both houses of Congress. Democratic margins under Biden, by contrast, were razor thin. The president and his party appeared to believe they could pass these mammoth bills on straight party-line votes and would then be rewarded by a grateful electorate after the fact. The only problem with this plan is that it gets the order of political operations exactly backwards, ignoring the deep and wide divides within the party as well as those within the electorate as a whole. There is no overwhelming majority in favor of progressive policymaking. Biden can't be another FDR.

Forgetting America's many fractious divisions in the early 21st century is always a big mistake, and I made it with my column of April 2. That's bad, even if I began to right myself less than a month later.

I'll do my best to avoid it in 2022 and beyond.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.