The Haitian migrant surge, explained

Thousands of Haitian migrants crossed into the United States this month, setting up camp under a bridge in Del Rio, Texas. Here's everything you need to know.

Thousands of Haitian migrants crossed into the United States this month, setting up camp under a bridge in Del Rio, Texas. The surge has put the Biden administration's immigration policies in the spotlight. Here's everything you need to know.

What caused this sudden influx?

Last week, an estimated 15,000 migrants, most of them native Haitians, were living in a makeshift camp in Del Rio. But the surge really began shortly after former President Donald Trump left office. A vast majority of the migrants seeking asylum haven't lived in Haiti for several years, having fled after a 7.0-magnitude earthquake devastated the country in 2010. They went to South America first, where there were job opportunities in countries like Brazil and Chile, but those have since dried up. Meanwhile, Chile enacted a stricter immigration law in April, and deportations rose. Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, and conditions there have only worsened thanks to the coronavirus pandemic, an increase in gang violence and murders, the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, and another catastrophic 7.2-magnitude quake. Short on options, many Haitians decided now was the time to journey to the U.S. for better opportunities, and they believed that "under the Biden administration, it might be easier to get into the U.S.," Jessica Bolter of the Migration Policy Institute told The Washington Post.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why do they believe that?

It mostly comes down to misinformation spread between friends and families. Many migrants say they heard through word of mouth that the U.S. border was open, and that it was relatively easy to cross into the country at Del Rio. But the reality is very different. The Department of Homeland Security is invoking Title 42 — a public health law first used under Trump — that allows the U.S. to expel migrants during a pandemic without giving them a chance to seek asylum. The Biden administration began expelling migrants from the camp last weekend, with the goal of having seven full flights a day to Haiti until the site is empty.

What are the conditions like in Del Rio?

Pretty awful. Because the journey to the U.S. takes several months for most migrants, they travel light and don't bring a lot of necessities. It's hot and crowded, with food and water in short supply, garbage piling up, and people sleeping in tightly packed tents or in the dirt. So far, 10 migrant women have been transported to local hospitals to deliver babies. Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas visited the site and told Congress a "human tragedy" was unfolding and the United States was working to quickly address it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Are any of the migrants allowed to stay?

Two U.S. officials told The Associated Press that many of the migrants are being released in the United States with notices to appear at an immigration office within 60 days. Giving them this option rather than ordering an appearance in immigration court cuts the time needed to process migrants. The decision-making process for who will be sent back to Haiti and who gets to remain in the U.S. hasn't been made public, but the officials told AP single adults are usually the ones being expelled, rather than pregnant women, families with young children, and people with medical issues. No unaccompanied minors are being put on the expulsion flights. While the administration has touted its deportation efforts, Biden is facing criticism from both ends of the political spectrum.

So Democrats and Republicans are both angry about the situation?

Yes, but for different reasons. Several GOP lawmakers have accused Biden of being too lenient on immigration, and suggest that's why so many migrants came to Del Rio. Some Democrats see the deportations as inhumane, and are outraged over images published earlier this week showing Border Patrol agents on horseback swirling their reins like whips as they chased migrants crossing the Rio Grande. White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki condemned the photos, saying they were "obviously horrific" and Border Patrol agents "should never be able to do it again." Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) demanded the Biden administration drop Title 42 and afford asylum seekers due process, telling him the U.S. cannot "continue these hateful and xenophobic Trump policies that disregard our refugee laws," and the United States' special envoy for Haiti, Daniel Foote, resigned, saying in a letter to Secretary of State Antony Blinken he would not be associated with the "inhumane, counterproductive decision" to deport the migrants back to Haiti, where conditions are so unstable. "Our policy approach to Haiti remains deeply flawed, and my recommendations have been ignored and dismissed, when not edited to project a narrative different from my own," he added.

What happens to the migrants after they are deported?

The migrants left Haiti for a reason — to escape poverty, violence, and instability — and don't want to return. While some are resigned to the fact they are back in Haiti, there have been at least two incidents at the Port-au-Prince airport in which deported migrants immediately tried to get on planes headed to the U.S. Maxine Orélian told AP that he attempted to board a flight to the U.S. because there are no opportunities in Haiti. "What can we provide for our family?" he said. "We can't do anything for our family here. There is nothing in this country."

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

-

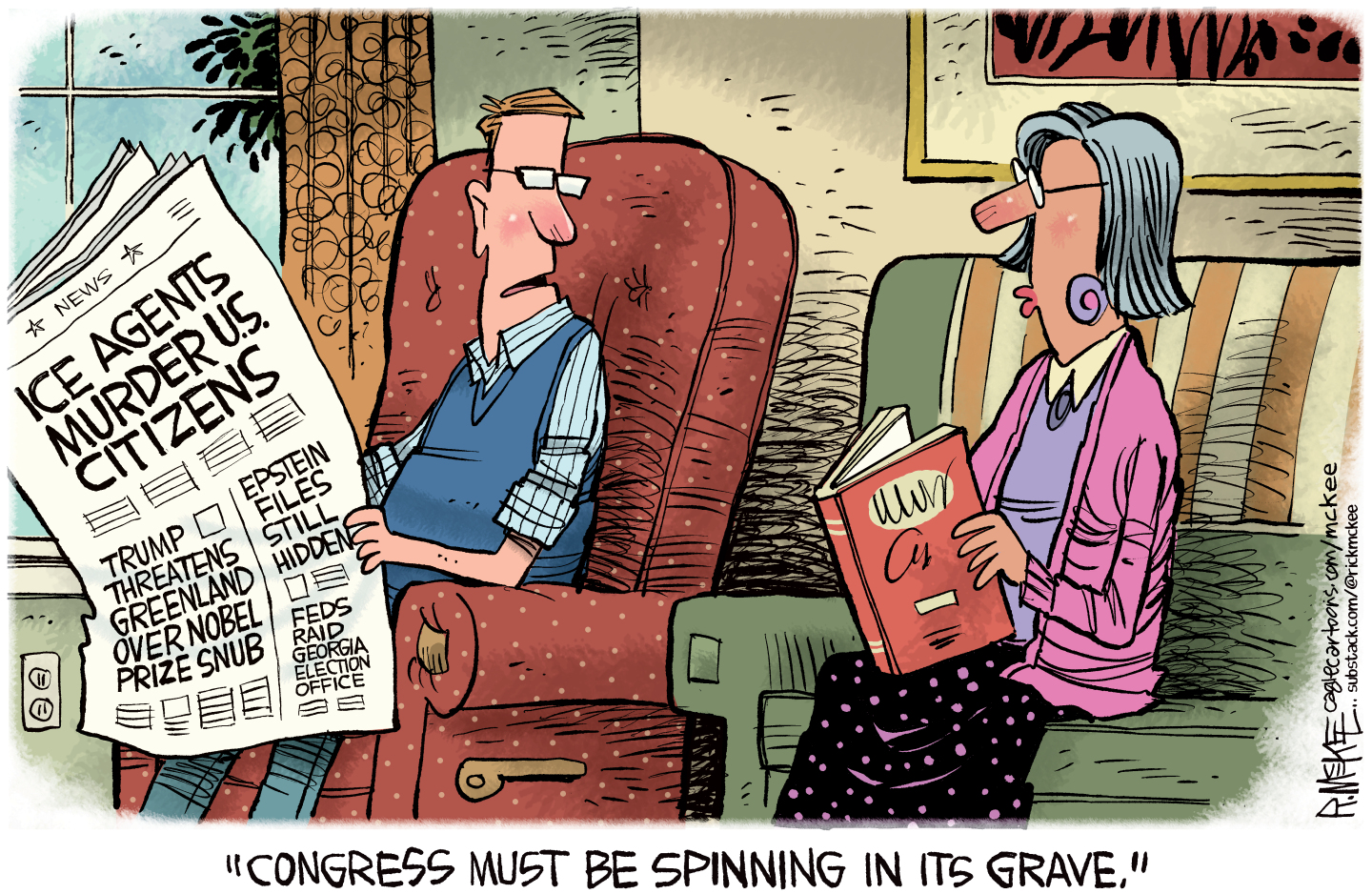

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

Judge slams ICE violations amid growing backlash

Judge slams ICE violations amid growing backlashSpeed Read ‘ICE is not a law unto itself,’ said a federal judge after the agency violated at least 96 court orders

-

Businesses are caught in the middle of ICE activities

Businesses are caught in the middle of ICE activitiesIn the Spotlight Many companies are being forced to choose a side in the ICE debate

-

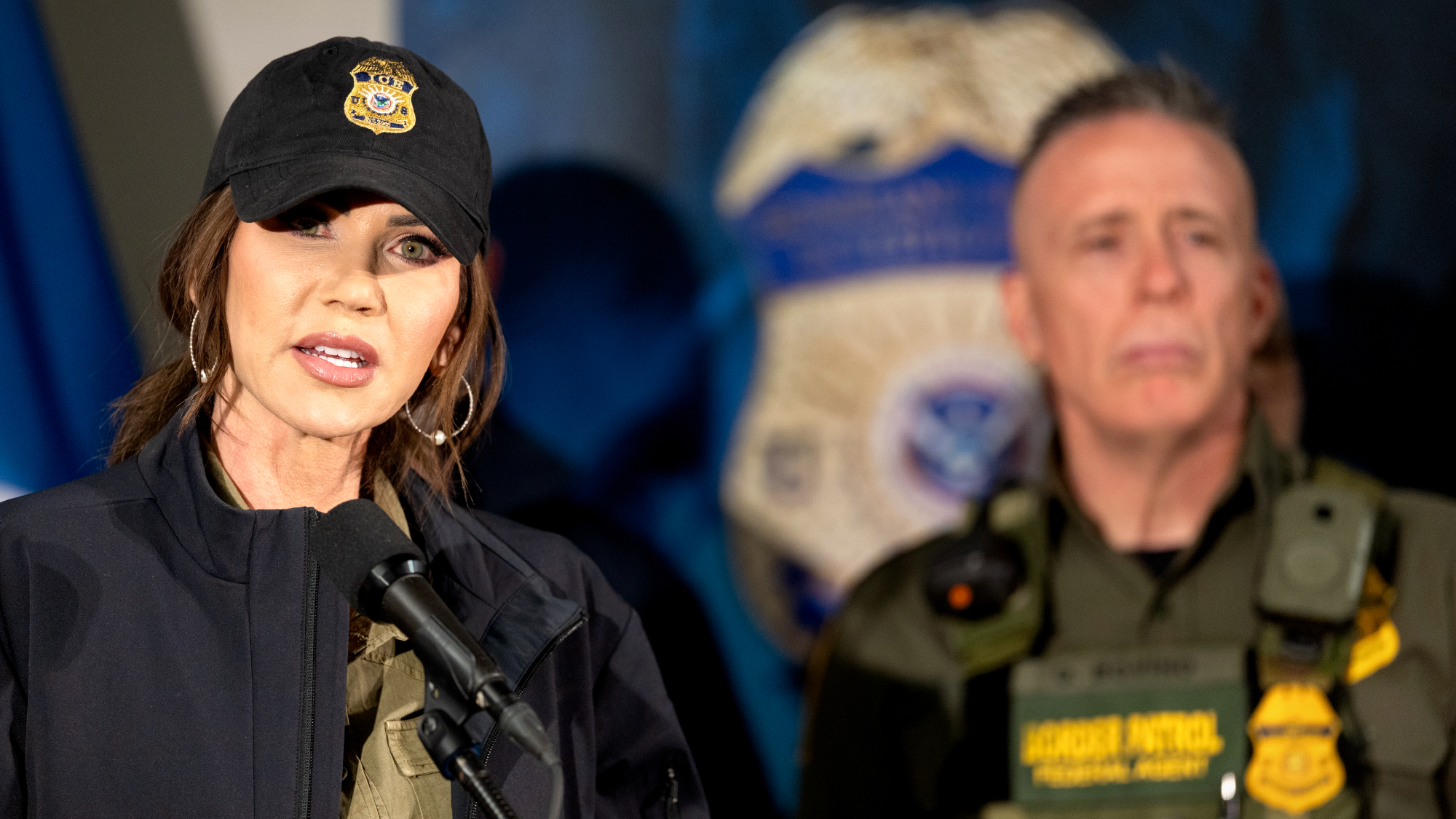

Democrats pledge Noem impeachment if not fired

Democrats pledge Noem impeachment if not firedSpeed Read Trump is publicly defending the Homeland Security secretary

-

‘Being a “hot” country does not make you a good country’

‘Being a “hot” country does not make you a good country’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

ICE: Now a lawless agency?

ICE: Now a lawless agency?Feature Polls show Americans do not approve of ICE tactics

-

Trump inches back ICE deployment in Minnesota

Trump inches back ICE deployment in MinnesotaSpeed Read The decision comes following the shooting of Alex Pretti by ICE agents

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America