What happens if the House can't pick a speaker?

It could go one of four ways

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

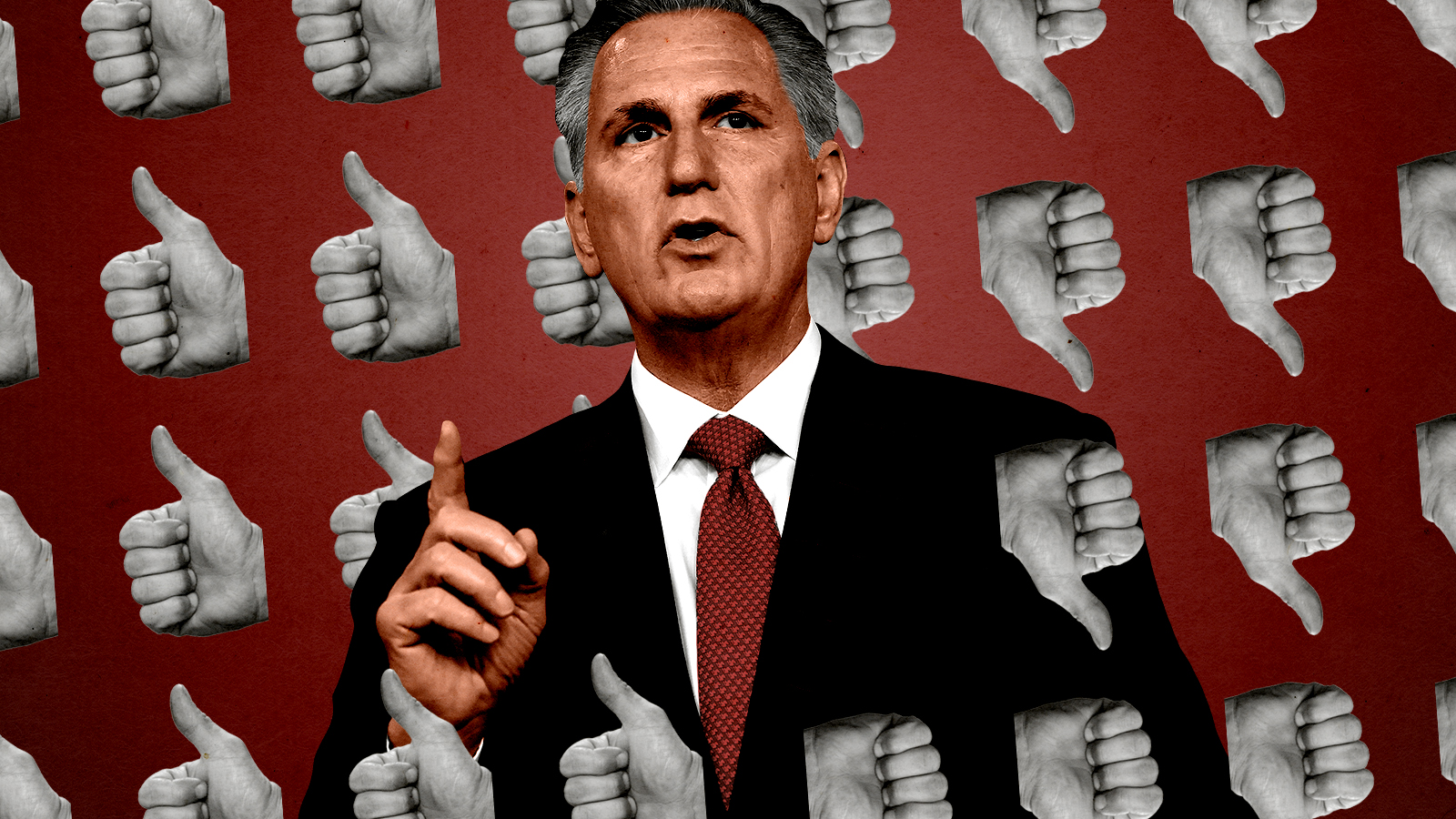

On Wednesday, Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) lost three more votes to be the speaker of the House, with his leadership bid held up by a faction of hardliners seeking greater influence in the lawmaking process and hoping to impose a variety of rules that would have the effect of weakening the position. The holdouts have coalesced behind Rep. Byron Donalds (R-Fla.).

It is the first time since 1923 that the majority party has needed to hold multiple ballots to select a speaker, and the spectacle has left the GOP in disarray. With no obvious path to resolving the standoff, what might happen now? Here's everything you need to know about potential scenarios for the next speaker of the House:

Moderates settle on a bipartisan compromise

If McCarthy keeps losing votes, and his competitors can't gain any traction, something will ultimately have to give. One leading Republican moderate in the House, Rep. Don Bacon of Nebraska, said after Wednesday afternoon's triple debacle that "at some point, it may require a bipartisan solution," and that he "doesn't like being held hostage."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There is, of course, no law that says the speaker must come from the party with the most seats. But it seems unlikely that this consensus choice, should there be one, would come from the Democratic side of the aisle. More likely, someone like Bacon himself would offer himself up to the Democrats and say, in effect, "it's me, or some Freedom Caucus bomb-thrower, or complete mayhem." If someone like Bacon, who has some purchase on the other side of the aisle, could get all 212 Democrats to support him, he would only need to convince five other Republicans to come along with him to hit the magic number of 218. That math gets much more complicated, though, if there are any Democrats who wouldn't sign on to such a compromise. The more Democrats who are unwilling to make a deal, the more Republicans Bacon would need to bring with him.

Of course, Bacon would have to agree to extensive power-sharing with Democrats that might look very much like a parliamentary-style coalition government. Coalition governments are not completely without precedent in U.S. history — Democrats and Republicans had one hammered out and ready to roll in 1917 before Democrat Champ Clark ultimately became speaker. In discussing why the U.S. has never seen a true coalition government, even at times like during the budget standoffs of President Barack Obama's second term, constitutional scholar Mark Tushnet argues that "whatever dysfunction there is in our contemporary national political process may not lie in the Constitution itself, but rather in subconstitutional arrangements."

In other words, the only thing standing between the U.S. and a coalition government in the House is the norm that it shouldn't happen. In countries with extensive experience with coalition rule, like Germany, no party has won a majority in the Bundestag since 1957 — and even that entity, the CDU/CSU, was itself an alliance.

A dark horse emerges

It's clear that the holdouts are attempting to grind McCarthy down by making him look weak, letting him lose vote after vote until — they hope — he gives up and steps aside. At that point, they would introduce a new candidate: not a Freedom Caucus stalwart but a more establishment candidate willing to capitulate to their rules demands, perhaps someone like Rep. Steve Scalise (R-La.). If Scalise agrees to the demands, it is a sign that those demands are more important than the identity of the speaker. If, on the other hand, he offers the same package as McCarthy and the holdouts fold, it means the whole thing was really about vengeance against McCarthy after all. Scalise is doing better than anyone but McCarthy on the PredictIt political betting market, so the chatter likely isn't idle.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All it takes is for someone to nominate Scalise, or Elise Stefanik (R-N.Y.), or even someone outside of the House, like former President Trump (who, it must be noted, is still backing McCarthy). Nothing in the Constitution requires that the speaker be a sitting member of the House — although that possibility remains more of a political nerd's weird fantasy than something that is likely to happen. The speaker is not a figurehead, but someone familiar with the intricacies of lawmaking and arm-twisting who needs to carefully wield power and influence every day. You can't just call one in from the bullpen and expect them to start throwing strikes.

McCarthy grinds away until he wins

Two hundred and twenty-two people trying to convince 20 people they are wrong is much easier than 20 people trying to convince 202 others that they're right. Right now, McCarthy and his allies seem dug in, as McCarthy himself promised in the contentious closed-door meeting of the GOP caucus before the first votes were taken on Tuesday.

However, McCarthy has actually lost a vote since the first ballot took place, while his opponents have cycled from voting for Rep. Andy Biggs (R-Ariz.) to Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio) and now to Donalds. Those 20 holdouts stuck together for three votes on Wednesday afternoon, and possibly more on Thursday. It's hard to see how they budge unless McCarthy caves on more of their demands.

On the other hand, McCarthy and any four of his closest allies can block anyone championed by the House Freedom Caucus holdouts from becoming speaker. If you're McCarthy, you'd certainly like to see the number of opponents dwindling with each ballot. It's probably worth noting that the last time this happened — 100 years ago in 1923 — the leading vote-getter on the first ballot, Republican Frederick Gillett of Massachusetts, eventually prevailed on the ninth try. Even the split was eerily similar, with Gillett winning 197 votes on the first ballot to 17 for his closest competition in the party.

Hakeem Jeffries becomes speaker

This is, admittedly, the least likely scenario. Democrats only control 212 seats in the House, and so under current rules, Jeffries, the presumptive minority leader, cannot become speaker just with Democratic votes. But those 212 Democrats could in theory wrangle a handful of Republicans to change the House rules and lower the threshold for becoming speaker to a plurality instead of an outright majority — something that last happened in 1855. Jeffries has already won that plurality six times and counting. One of the recalcitrant Republicans, Rep. Matt Gaez (R-Fla.), has said publicly that he doesn't care if Jeffries becomes speaker if GOP leadership won't agree to the holdouts' demands.

A Democrat leading what would, in effect, be a minority government might not be much more functional over the next two years than one led by McCarthy. But for Democrats, they would at least have the assurance that the House would not spend all of its time ginning up bogus investigations into President Biden. That would be a bitter pill for Republicans to swallow, and GOP leaders would have a tough time explaining to their voters why they won a majority in the House yet somehow managed to screw it up so badly that a Democrat is still running the chamber.

The House must pass a rules package by Jan. 13, or we are in mostly uncharted territory. Expect a lot more drama as that deadline approaches. Until a resolution is reached, the United States is functionally without the services of one of its national legislatures — an outcome that serves no one.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Why are Republicans leaving Congress?

Why are Republicans leaving Congress?Today's Big Question GOP dysfunction puts the House majority at risk

-

'Elections should be — and often have been — clarifying'

'Elections should be — and often have been — clarifying'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Kevin McCarthy let the House win

Kevin McCarthy let the House winThe Explainer A burnt out former Speaker decides it's better to fade away.

-

House passes GOP spending bill as Democrats shrug off 'goofy' laddered structure

House passes GOP spending bill as Democrats shrug off 'goofy' laddered structureSpeed Read House Speaker Mike Johnson had to rely on Democrats to fund the government through at least Jan. 19, though some found his methods a little bizarre

-

Has the GOP speaker's race gone from firing squad to royal rumble?

Has the GOP speaker's race gone from firing squad to royal rumble?Today's Big Question What was once a single-file sequence of aspiring Republican speakers is degenerating into a nine-person free-for-all

-

Rep. Jim Jordan's speaker bid: Are Republicans damned either way?

Rep. Jim Jordan's speaker bid: Are Republicans damned either way?Today's Big Question Win or lose, Ohio congressman's quest for the gavel could backfire on the GOP in a big way

-

Scalise drops House speaker bid a day after winning GOP nomination. What happens now?

Scalise drops House speaker bid a day after winning GOP nomination. What happens now?Speed Read The House majority leader was the GOP's choice to succeed Kevin McCarthy, except he did not have enough Republican votes to seal the deal

-

Is Rep. Steve Scalise's speaker bid already doomed to fail?

Is Rep. Steve Scalise's speaker bid already doomed to fail?Today's Big Question A narrow victory among the House Republican caucus could be a sign of trouble to come for the Louisiana conservative