Cop26: how the UK is doing on three key net zero pledges

Boris Johnson is calling for urgent action at climate summit in Glasgow - but is Britain on course to meet his 2050 target?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Experts Ashley Fly, Grant Wilson and Ljubomir Jankovic assess whether the prime minister is delivering on his climate promises

The UK is hosting the 26th annual UN climate summit in Glasgow. Boris Johnson’s government boasts of having the most ambitious climate change targets in the world.

But how is the country’s progress to net zero emissions by 2050 going? Three experts look at three key pledges.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Transport

Pledge: to phase out sales of petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030.

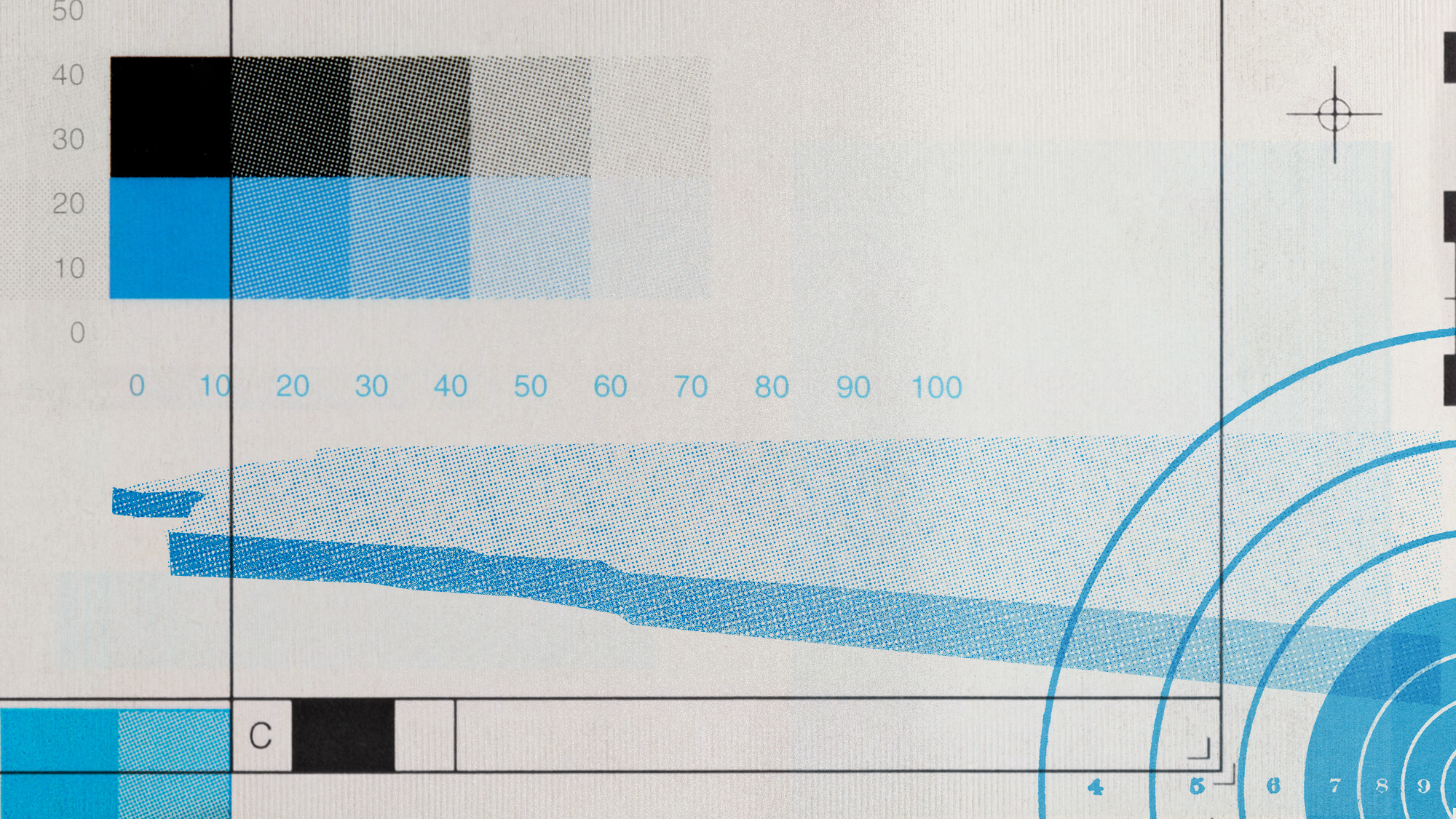

Progress: electric vehicles, or EVs, accounted for 15.2% of all new UK vehicle registrations in September 2021, up from an average of 6.6% in 2020 and 1.6% in 2019. There are now almost 100 different EV models to choose from and a growing network of nearly 5,000 rapid chargers, up from 2,000 in 2018.

In Norway, a country which is aiming for a more ambitious 2025 ban on petrol and diesel vehicles, nearly 80% of all vehicle sales in September were electric, up from 54.3% in 2020.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Norway has demonstrated that a transition to electric vehicles is possible with current technologies if attractive policies, such as EV tax exemptions, are in place.

There are lots of hurdles which the UK must overcome to achieve its own 100% EV sales target by 2030, such as households which lack driveways to charge their EVs at home and the commercial van sector, which will also fall under the ban. The government can help by installing more on-street charging points, simplifying the use of rapid charging points so they can all take contactless payment, and working with manufacturers to offer test drives. Electric vans currently qualify for government grants worth up to £6,000, but businesses may need more generous incentives.

As the rest of the world rushes to meet their own EV targets, there could be a shortage of materials, parts and skills to make enough to keep up with demand. This could cause the price of EVs to rise or overwhelm waiting lists. One solution is to invest in the UK’s automotive sector and develop a flexible domestic supply chain with a network of gigafactories to produce the millions of batteries needed.

Overall, the signs are looking good for high levels of EV purchasing in the near future, but it’s not time to take the foot off the zero emission gas just yet.

Electricity

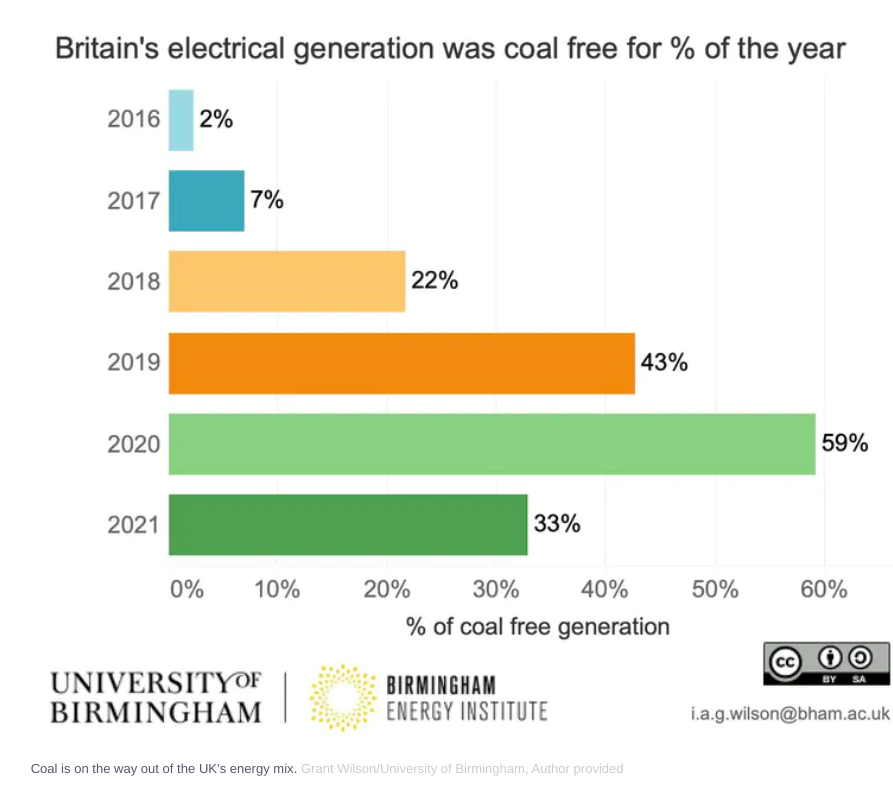

Pledge: to stop burning coal to generate electricity by 1 October 2024.

Progress: the UK’s rapid elimination of coal-fired power since 2015 has been possible due to three factors: a fall in electricity demand, an increase in renewable generation (wind and to a lesser degree solar) and a shift from coal to gas generation.

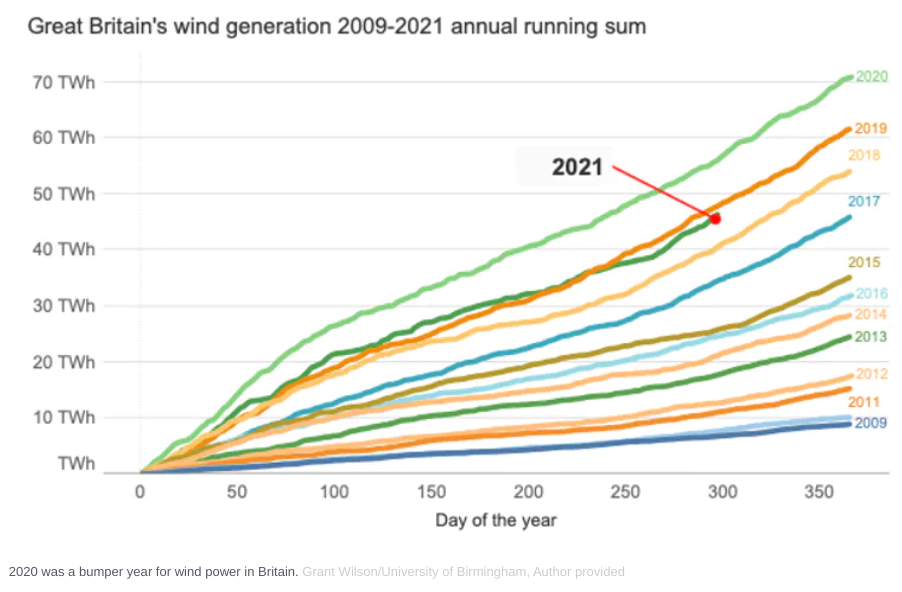

However, there is still a residual amount of coal generation that has supplied between 1% and 2% of electricity demand at an annual level from 2019 to 2021. Coal is on track to generate around six terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity in 2021. The drop in wind generation from 2020 to 2021 alone (largely due to an unusually calm summer) has been around 6-8 TWh.

Coal remains a flexible source of generation that can be called upon to fill gaps when other sources are struggling or to help with unforeseen outages. This happened in September when the interconnector cable that imports electricity from France was taken offline due to a fire.

A new electrical interconnector to Norway could further reduce the country’s dependence on generation from coal. Energy companies are also introducing time of use tariffs which nudge customers to shift electrical demand away from expensive peak periods such as weekday evenings – when coal is traditionally used to fill short-term gaps in supply – by passing on the higher cost of electricity at these times.

The shift from coal is merely a step towards fully decarbonising the electrical system. The next is to remove natural gas. It’s entirely plausible that Britain will remove coal-generated electricity by October 2024, but keeping it out will depend on finding low-carbon means of balancing electricity supply and demand.

That will mean making the electrical system more resilient to shocks, such as the sudden loss of power or high demand. EVs can help, by supplying electricity back to the grid when needed – effectively acting as small, distributed batteries. But by the time meaningful levels of controllable demand (and potentially supply) from EV charging are available to the system, coal generation will be long gone.

The other major challenge is balancing the system between seasons and years. Britain uses much more energy in winter than summer. As more energy generation (as well as demand) becomes dependent on the weather, Britain will have to prepare for years with significantly lower output from wind in particular. Coal excels here, with cost-effective stockpiles which can be turned into months of electricity supply. Batteries, pumped water and other forms of short-term electrical storage will never reach these sorts of scales. Without coal, energy system operators must find low-carbon solutions to this challenge of seasonal balancing.

It will be surprising if coal generation lasts quite as long as October 2024 in Britain, and the milestone is one that should be rightly celebrated when it happens. However, the longer term storage that coal provided (and gas and nuclear still do) is something that Britain’s needs to address for a low-carbon electrical sector that is resilient to sustained low wind weather events.

Heating

Pledge: to ensure all new heating systems installed in UK homes are low-carbon from 2035.

Progress: a range of measures and technologies can contribute to this target. One of the government’s preferred options, according to a recent report, is replacing boilers which burn natural gas (a fossil fuel) with heat pumps, which run on electricity.

Heat pumps transfer warm air from a lower outside or ground temperature to a higher inside temperature, using one-third the energy of a gas boiler for the same level of heating. If the energy source powering it is renewable, operating a heat pump is emission-free.

Homes with a heat pump may have cooler radiators compared with a gas boiler. Bath or shower water will also not be as warm. This means that as well as installing the pump, home central heating systems need bigger radiators and larger hot water storage tanks with additional heaters.

The cost could be up to £18,000 per house. The government has offered a £5,000 grant towards this, meaning households will need to part with a lot of their own cash and go through with a major renovation.

The new £450m boiler upgrade scheme could install 90,000 heat pumps (at £5,000 per heat pump upgrade) if it reaches the building owners willing to part with more than twice that in their own cash. This represents less than 0.4% of the UK’s 23.9m homes. How are the remaining 99.6% going to become low-carbon?

Replacing natural gas boilers with ones powered by clean-burning hydrogen would be a more straightforward solution. Both are similar in size and deliver similar water temperatures. Hydrogen heating trials are under way in some parts of the UK. But pure hydrogen cannot pass through existing gas pipes, so new distribution infrastructure is needed.

The UK’s government ten point plan for a green industrial revolution aims to develop five gigawatts of low-carbon hydrogen production by 2030. This is thought to be sufficient to power 1.5m homes. That would still leave at least 22.3m homes without a clean heating solution, assuming that all of the 90,000 homes take the offer of replacing their gas boiler with heat pumps.

The boiler upgrade scheme is a part of £3.9bn new funding announced in October 2021 that will include hydrogen heating. However, a recent report suggested that developing hydrogen production technology – alone – by 2035 would cost between £3.5bn and £11.4bn. Further investments in converting, storing and distributing hydrogen fuel are also needed.

All these measures would mean throwing good money after bad if nothing is done to improve the energy efficiency of existing homes. It’s thought that 80% of the homes which will exist in 2050 – 19.1m – have already been built. That means 19.1m of today’s homes still being lived in by the middle of the century. Since there are 10,288 days before 1 January 2050, approximately 1,860 homes will need to be renovated every day in order to be done by 2050. With the green homes grant which offers £5,000 towards home insulation, it remains to be seen how such a large undertaking will be carried out, and how it would be paid for.

Will all new heating systems in UK homes be low-carbon from 2035? Current government commitments only scratch the surface. Although efforts are going in the right direction, the government will need to significantly increase investment to meet its target.

Ashley Fly, lecturer in vehicle electrification, Loughborough University; Grant Wilson, lecturer, Energy Informatics Group, chemical engineering, University of Birmingham, and Ljubomir Jankovic, professor of advanced building design, University of Hertfordshire.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

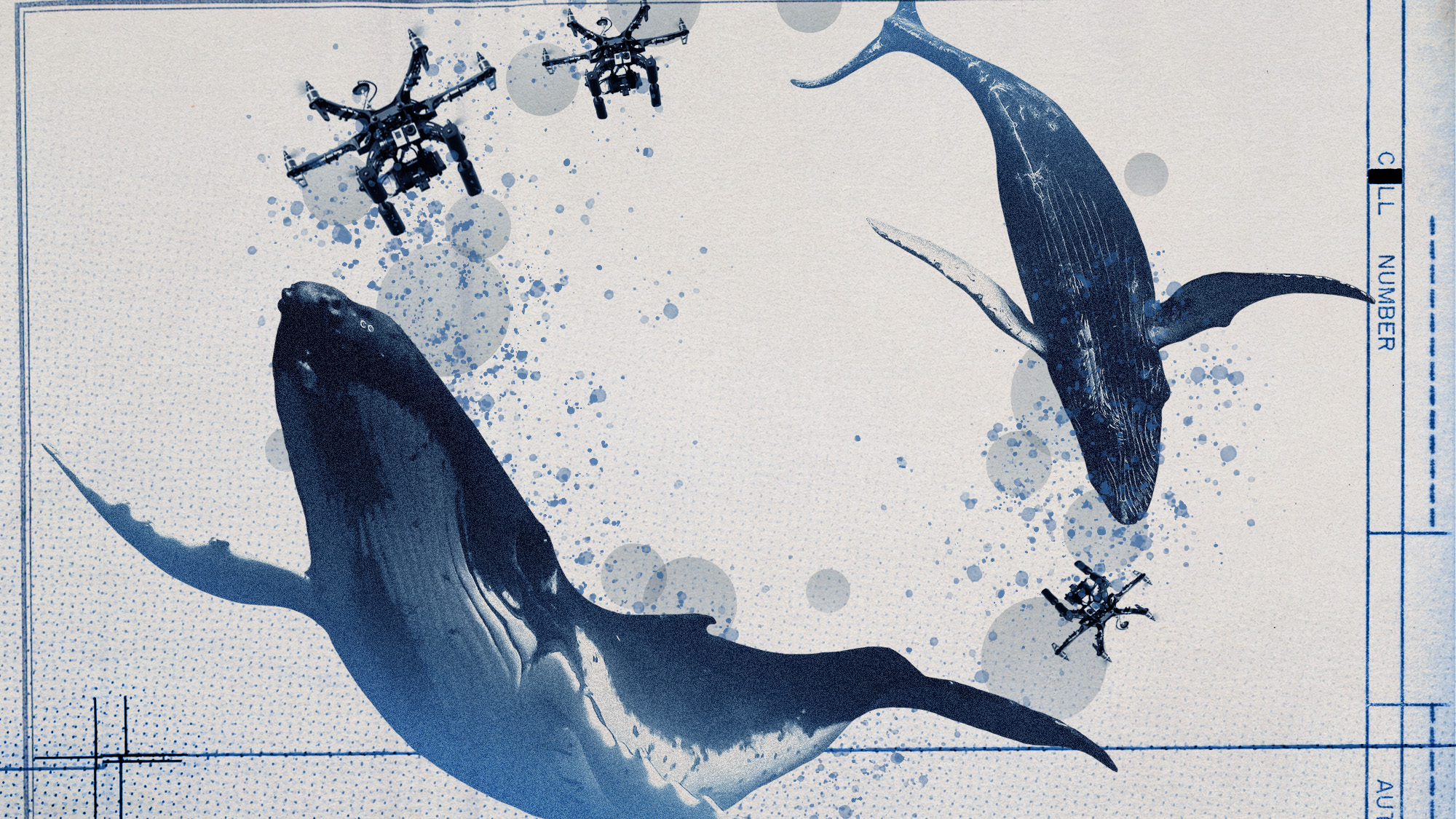

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures