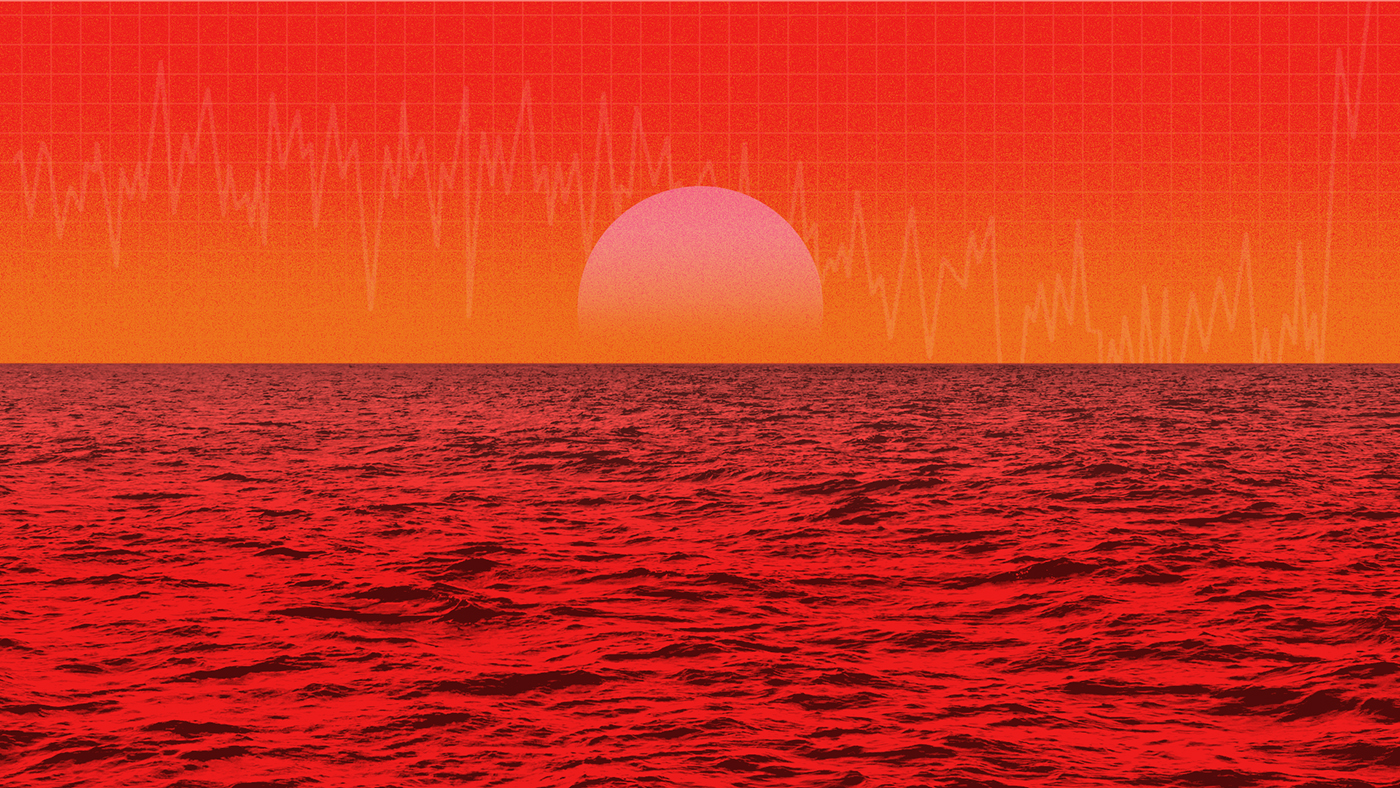

The surprising and rapid rise in ocean temperatures

Sea-surface temperatures are hitting record highs, confounding experts

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ocean temperatures were warmer in April than scientists have ever observed at this time of year, with experts struggling to account for the rapid recent rise.

“The world’s oceans are running a fever,” said National Geographic. Sea-surface temperatures have been hitting record highs, leading to “marine heatwaves” around the globe, added The Guardian.

According to US government data, the average temperature at the ocean’s surface has been 21.1C since the start of April, beating the previous record of 21C set in 2016.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That might not sound like a lot, says Robert Rohde, a lead scientist at Berkeley Earth told Wired, “but in ocean terms two-tenths [above the global average] is actually a lot because it doesn’t warm as quickly as the land”.

“Averaged over the planet, that’s a really big anomaly,” said Alex Sen Gupta, a research scientist at the Climate Change Research Centre at the University of New South Wales in Australia, in The Washington Post.

Why are the oceans warming?

Some experts think the heating spike is the “vanguard of a looming El Niño event, which is characterized by unusual warmth of the sea surface across a vast swath of the equatorial Pacific”, said Discover Magazine.

For the past three years, La Niña conditions, which are characterised by cooling in the central and eastern tropical Pacific, have helped suppress temperatures. But that has now come to an end.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

“When you run your air conditioner, you’re masking the heat outside,” explained oceanography professor Moninya Roughan for The Conversation. “It’s the same for our oceans. La Niña brought three years of cooler conditions, while global warming continued apace.”

“Now that it’s over, we are likely seeing the climate change signal coming through loud and clear,” Dr Mike McPhaden, a senior research scientist at the Washington-based National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, told The Guardian. He and other experts predict a potential El Niño pattern in the tropical Pacific later this year that could increase the risk of extreme weather conditions.

“Historically, El Niño is known for accelerating global warming, with devastating effect,” said The Washington Post. “The pattern is marked by warmer-than-average surface waters in the Pacific Ocean that have domino effects on weather around the world.”

Are humans to blame?

“Climate change is the big picture – nine-tenths of all heat trapped by greenhouse gases goes into the oceans,” said Roughan for The Conversation.

Human interference in the climate is certainly making matters worse, agreed National Geographic. “Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution a few hundred years ago, humans have burned massive amounts of fossil fuels; cut down huge swaths of forest; and undertaken many other activities that pump heat-trapping carbon dioxide into Earth’s atmosphere,” the magazine said.

About 1% of that trapped heat has stayed in the atmosphere, while most of the rest has been absorbed by the planet’s oceans. The warming is now speeding up, with the top part warming up about 24% faster than it did a few decades ago, according to a 2019 study cited by the magazine.

“These ups and downs related to La Niña and El Niño, they are temporary,” McPhaden told The Washington Post. “The real issue is the rising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, which are going up and up and up.”

What are the effects?

The effects of warmer waters could have a devastating impact on marine life. “Most ocean dwellers, from plankton to fish to whales, live in the upper section of the ocean, squarely in the zone where temperatures are increasing quickest,” said National Geographic, and they are highly sensitive to temperature changes.

The ocean food chain depends on the natural circulation of water, with cold water in the depths upwelling to the surface, bringing with it nutrients to fertilise phytoplankton, explained Wired. When the water heats up, the phytoplankton stratifies, becoming a cap which sits on top of the cold waters, drastically reducing the food supply for tiny creatures called zooplankton.

With more heat creating more moisture in the air, storms will become more ferocious, and ice sheets more unstable. What’s more, as the oceans heat up, they expand, causing sea levels to rise, affecting coastlines and leading to extreme flooding.

“Translation: What might seem like a small uptick in temperature can have profound effects,” concluded The Washington Post.

Felicity Capon is senior editor of The Week Junior, where she oversees the magazine’s international news section. She was the title’s editor for several years, during which she was shortlisted for the BSME Fiona Macpherson Best New Editor award. She also appeared on The Emma Barnett Show on Radio 5 Live, The Sarah Brett Show and the Media Masters podcast. She is a regular contributor to The Week Unwrapped podcast, and has written for The Week, The New Statesman, The Times, The Telegraph and Newsweek.