Pelé obituary: remembering the greatest footballer of all time

The Brazilian footballer, who died aged 82, was blessed with extraordinary skill in every aspect of the game

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

He was football’s “first global superstar”, and by common consensus its greatest player, said The Times. Pelé, who has died at the age of 82, was blessed with extraordinary skill in every aspect of the game. Both “physically powerful and graced with a feline speed”, he could shoot from distance, or “simply walk the ball into the net after dribbling past an entire defence”.

In a career spanning three decades and 1,363 matches, the Brazilian scored 1,280 goals and propelled his country to three World Cup victories. Such was his brilliance, he became a hero to millions, inspiring quasi-religious adoration wherever he went.

When a reporter suggested he was as famous as the Son of God, Pelé, without any sense of boastfulness, agreed that might be so, noting there were parts of the world “where Jesus Christ isn’t so well known”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Early life

Christened Edson Arantes do Nascimento – after Thomas Edison – Pelé was born in the small city of Três Corações, in southeastern Brazil, in 1940. He picked up the nickname Pelé in early childhood, said The New York Times, a name some think was derived from his mispronouncing the name of a local goalkeeper, Bilé.

Pelé’s father, himself a gifted footballer, moved the family to São Paulo state when his son was small, in the hope of reviving his career. Instead, he suffered a career-ending knee injury and the family fell into poverty. Unable to afford a football, Pelé was forced to hone his skills kicking around a grapefruit, or a sock stuffed with newspapers. He would practise for hours on end – often watched by gawping neighbours.

His mother, Celeste, was adamant that Pelé shouldn’t follow in her husband’s footsteps, but his prodigious success as a junior attracted the attention of the big clubs in Rio and São Paulo, and by the time he was a teenager, scouts were queuing up to sign him.

Santos FC

At the age of 15, Pelé joined Santos FC, the club he was to represent for the next 18 years. He scored four goals in his very first appearance, and in his first full season became the club’s top scorer, a feat that earned him a call-up to the national team.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Yet when Brazil turned up in Sweden for the 1958 World Cup, “hardly anyone noticed” the 17-year-old striker they had in tow, said The Sunday Times. “I was so skinny, quite a few people thought I was the mascot,” Pelé recalled. He missed the first two games owing to a knee injury, but once he got to play it was impossible any longer to ignore him.

He scored six times in Brazil’s final three games: that included a hat-trick against France in the semi-final – “I’d rather play against ten Germans than one Brazilian,” the French goalkeeper said afterwards – and a further two goals in the final against Sweden, which his side won 5-2.

Brazil had never won a World Cup before; now, thanks to their young star, they became the most feared side in the world overnight.

World Cups

Back in Brazil, Pelé continued to score goals at an astonishing rate, said The Daily Telegraph. In 1959, he scored a total of 126; two years later, he led Santos to their first league title. Such feats inevitably attracted the interest of top European clubs, but thanks to a 1961 presidential edict, classifying him as a “nonexportable national treasure”, Pelé was forced to stay in Brazil.

However, to maximise the earning potential of their star player, Santos took to organising regular exhibition tours of Europe, which often involved playing as many as ten matches in 15 days. Thanks in part to these “horrendous schedules”, Pelé arrived at the 1962 World Cup with a groin strain, and was forced to sit out the final few matches as his country claimed their second title in a row.

Greater disappointment was to follow at the 1966 World Cup, when defenders “hacked Pelé down at the knees”, forcing him to limp out of the tournament, said The Guardian. Disheartened, he vowed never to play international football again.

But four years later he changed his mind, and went to Mexico for the 1970 World Cup surrounded by a new generation of gifted players, including Tostão, Rivellino and Carlos Alberto. It was the first World Cup to be filmed in colour, and the first to be watched live by a global TV audience.

In an epic match against the defending champions, England, a quite brilliant header by Pelé was saved by England keeper Gordon Banks. “I’ve scored more than a thousand goals in my life,” Pelé later reflected, “and the thing people always talk to me about is the one I didn’t score.”

At the final whistle, Pelé and the England captain, Bobby Moore, who became his good friend, embraced like two battered prize fighters. Then in a mesmerising final, Brazil beat Italy 4-1, “playing football of such imagination and thrilling execution that it is regarded as one of the high-water marks in the history of sport”.

With their swaggering futebol-arte, the team proved it was possible to win by playing with joyful exuberance – and there was no more potent symbol of this than their “universally idolised” No. 10. It was his swan song.

Retirement

Pelé played only five more matches for Brazil, and officially retired from club football in 1974, said the Daily Mail. His career had an unexpected postscript, however. In a deal partly brokered by Henry Kissinger, he came out of retirement in 1975 to sign for the US team New York Cosmos.

The move was presented as a diplomatic coup – a chance for football’s biggest star to promote the sport in the US – but Pelé was mainly motivated by money: after several disastrous business dealings, he had twice lost a fortune and come close to being declared bankrupt.

That wasn’t the only way in which Pelé the man failed to live up to his Godlike image, said Marcus Alves in The Daily Telegraph. He was often criticised for failing to speak out against racism; he cruelly refused to acknowledge paternity of a daughter who was quite clearly his own; he seemed quite ready to tarnish his legacy by endorsing any product – including Viagra in the early 2000s – if it paid well.

Pelé was no saint, said Oliver Brown in the same paper, but it is undeniable that his impact on the world was overwhelmingly positive. He was quite simply, along with Muhammad Ali, the greatest athlete of the 20th century, a man who raised the spirits of his country, and brought “intoxicating joy” to millions.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Indiana beats Miami for college football title

Indiana beats Miami for college football titleSpeed Read The victory completed Indiana’s unbeaten season

-

Who is to blame for Maccabi Tel Aviv fan-ban blunder?

Who is to blame for Maccabi Tel Aviv fan-ban blunder?Today’s Big Question MPs call for resignation of West Midlands Police chief constable over ‘dodgy’ justification of ban from Aston Villa match, but role of Birmingham Safety Advisory Group also under scrutiny

-

Amorim follows Maresca out of Premier League after ‘awful’ season

Amorim follows Maresca out of Premier League after ‘awful’ seasonIn the Spotlight Manchester United head coach sacked after dismal results and outburst against leadership, echoing comments by Chelsea boss when he quit last week

-

Coaches’ salary buyouts are generating questions for colleges

Coaches’ salary buyouts are generating questions for collegesUnder the Radar ‘The math doesn’t seem to math,’ one expert said

-

Five years after his death, Diego Maradona’s family demand justice

Five years after his death, Diego Maradona’s family demand justiceIn the Spotlight Argentine football legend’s medical team accused of negligent homicide and will stand trial – again – next year

-

Libya's 'curious' football cup, played in Italy to empty stadiums

Libya's 'curious' football cup, played in Italy to empty stadiumsUnder The Radar 'Curious collaboration' saw Al-Ahli Tripoli crowned league champions in Milan before a handful of spectators

-

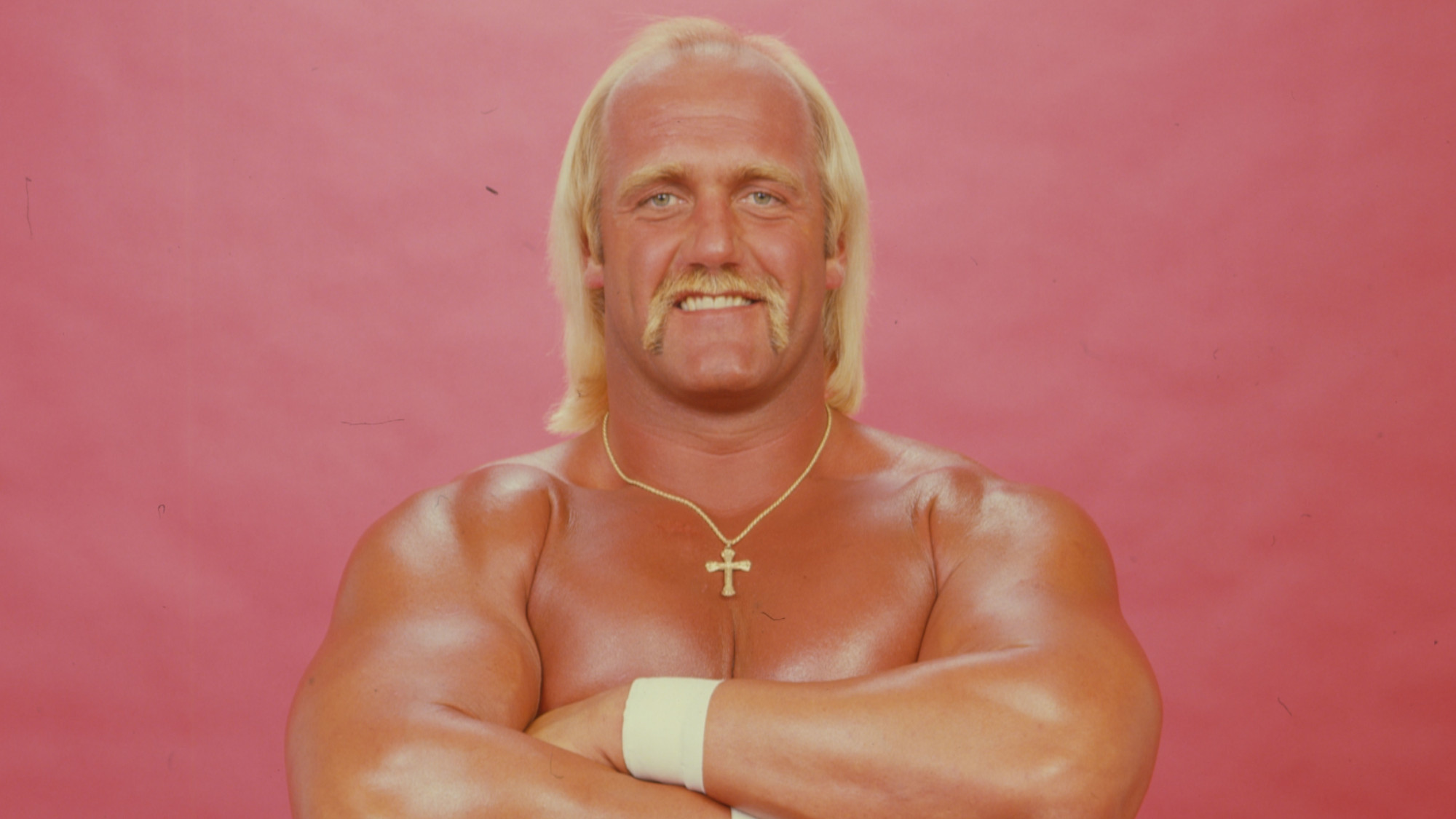

Hulk Hogan

Hulk HoganFeature The pro wrestler who turned heel in art and life