The rise of the superbugs: why antibiotic resistance is a ‘slow-moving pandemic’

The emergence of germs that are resistant to most drugs is one of the biggest public health challenges of our time

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

More than 700,000 people die every year because they are infected with microbes – bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites – that have become resistant to most known drugs.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is already a major public health problem around the world, though its effects are felt unequally: while an estimated 17% of infections in OECD countries are caused by drug-resistant microbes, 40%-60% of infections in Brazil, Indonesia and Russia are caused by such microbes.

Left unchecked, AMR threatens to become one of the world’s biggest health problems, surpassing diabetes and cancer. If more bugs become drug resistant, common infections could become untreatable, and routine treatments – chemotherapy, caesareans, hip replacements – too risky to carry out.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In 2019, a UN report estimated that drug-resistant microbes could lead to ten million deaths per year, and cost the world $100trn, by 2050. The Wellcome Trust has called AMR a “slow-moving pandemic”.

How do microbes become resistant?

Because of evolution by natural selection. Each time living things reproduce, their genetic code mutates. Often those mutations have little impact on the next generation. But sometimes they confer a survival advantage – perhaps the new generation of microbes need less food or water to survive, or maybe they are unaffected by the drugs that used to kill their ancestors.

Anti-microbial drugs increase the selection pressure: newer, resistant bugs survive and reproduce further. Over time, the only microbes that are left are the ones resistant to common drugs.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

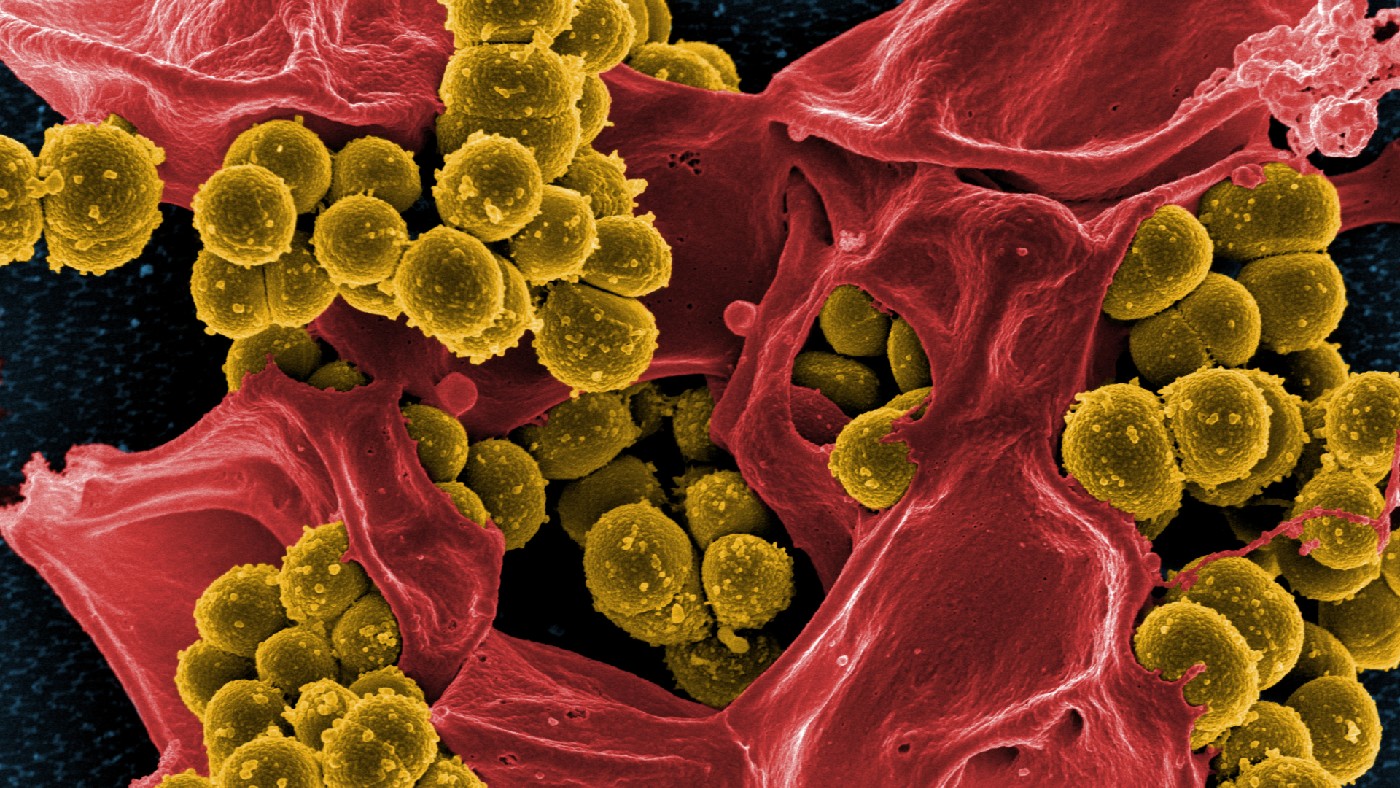

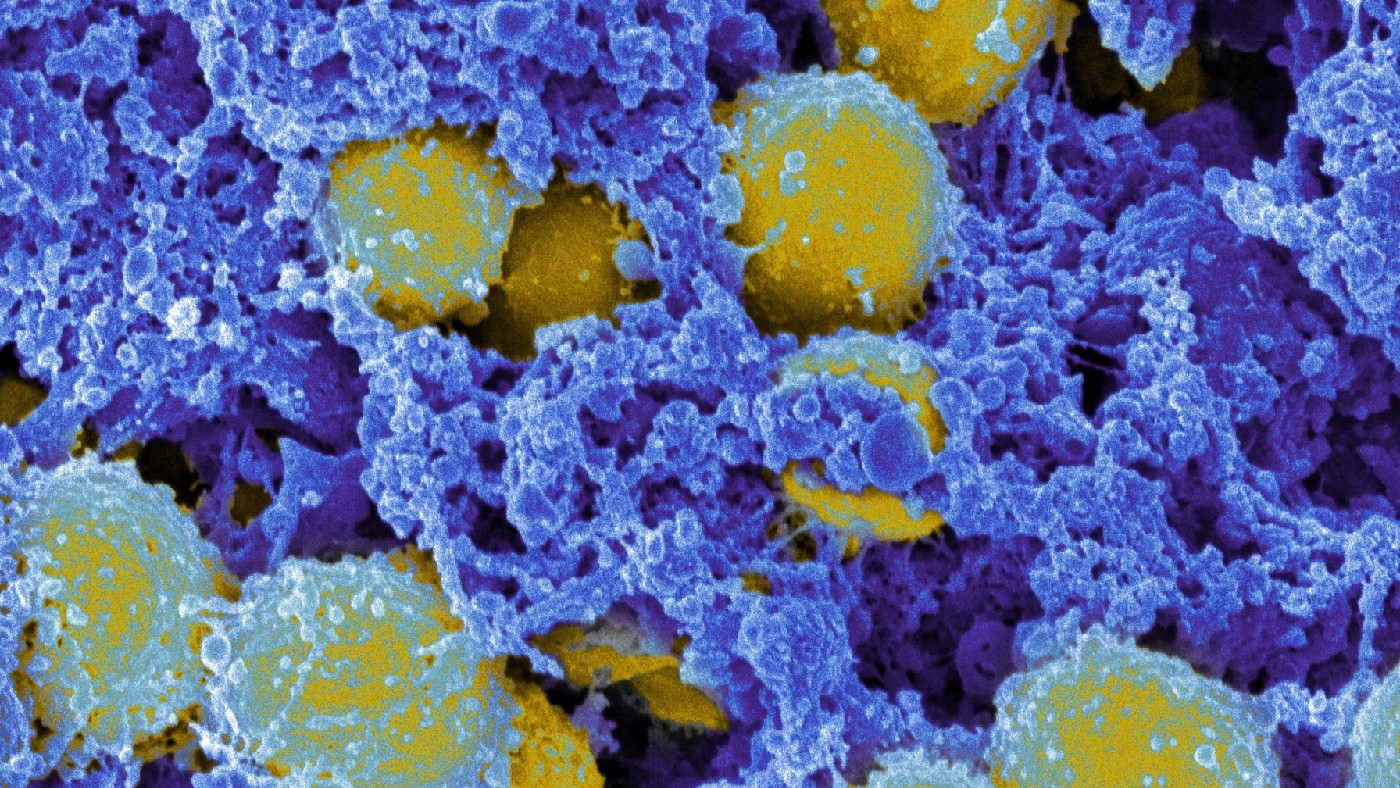

The most infamous examples of so-called “superbugs” are methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and drug-resistant tuberculosis – both caused by bacteria that are very difficult to treat with existing medicines. Drug resistance is nothing new, but the rate at which resistant bugs are appearing is growing fast and, worryingly, the supply of new drugs with which to treat them is drying up.

MRSA: the arms race

Alexander Fleming was studying Staphylococcus aureus – a bacterium that causes boils, abscesses, pneumonia and infections of surgical wounds and blood, sometimes causing fatal sepsis – when he discovered penicillin in 1928.

Penicillin revolutionised the treatment of staphylococcal (and other) infections, but its power soon began to wane: the first penicillin-resistant staphylococci were seen in 1942; they had evolved to make penicillinase, a penicillin-destroying enzyme.

In response, methicillin was developed – an antibiotic that was resistant to penicillinase. Soon after that, in 1961, scientists noticed the first methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). In 1963, the first recorded outbreak occurred, in a Surrey hospital.

Since then, MRSA has spread around the world, evolving independently, generally in hospitals, in places from the US to Taiwan. By 2005, it was killing more Americans than HIV. About one in 30 healthy people in industrialised nations are now “colonised” by MRSA, living harmlessly on their skin or nose. Its resistance to traditional antibiotics makes infections difficult to treat. About half of cases respond to the “last resort” antibiotic vancomycin, but its use has in turn created a vancomycin-resistant strain: VRSA.

Why are more resistant bugs appearing?

Largely because of the overuse and misuse of antibiotics – antimicrobial drugs that work against bacteria – which drives the evolution of resistance. Doctors will often prescribe antibiotics based only on a patient’s symptoms, instead of knowing there is a bacterium causing the illness.

Even when they would prefer to be cautious, many doctors report pressure to prescribe antibiotics to demanding patients (a recent US poll showed that over 40% of adults don’t understand that antibiotics are ineffective against viruses).

Patients also misuse them, by not finishing the course or by sharing drugs with friends or relatives. Every infected patient who does not use antibiotics properly is a potential breeding ground for drug-resistant bacteria.

Surely it’s not all patients’ fault?

No: by weight, most (perhaps 70%-80%) antimicrobials in use today are given to animals, especially on livestock farms; sometimes as a prophylactic treatment for entire herds, or to promote growth.

Antibiotics are widely used in fish farms and are almost entirely unregulated in the countries that use most of them – such as China, India, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Excessive use of antimicrobials in animals has been directly linked to AMR in people – genes from resistant animal microbes can transfer into human microbes, for example, or the resistant animal microbe might jump species into humans, a so-called “zoonotic transfer” that can cause an entirely new disease in people.

How do we tackle these problems?

The first step is to use antibiotics more sparingly. To help doctors to know when to properly prescribe them, they need cheaper, faster diagnostic tests that tell them whether an illness is caused by the kind of microbe that can be treated with available drugs.

Jim O’Neill, an economist who led a UK government review into the AMR crisis in 2016, noted that he found it “incredible that doctors must still prescribe antibiotics based only on their immediate assessment of a patient’s symptoms, just like they used to when antibiotics first entered common use in the 1950s”.

A range of programmes have been designed to prevent the misuse of antibiotics; beyond that, it is largely a question of hospital hygiene, and finding new drugs.

Why is the supply of new drugs drying up?

Mostly because the pharmaceutical companies that should have been discovering them have been chasing more lucrative drugs. The decades after the Second World War were a golden age for antibiotics, and a steady stream of new drugs reached the market. The rate of discovery fell dramatically at the turn of the 1980s, however – partly because the low-hanging fruit of the naturally-occurring antibiotics, such as penicillin, had been found.

In recent decades, both industry and government funding into antibiotics dwindled because tackling infectious diseases was seen as yesterday’s priority; pharma companies wound down their antibiotics research teams. The economics are difficult: it can cost $1bn to bring a new drug to market, and antibiotics (unlike, say, cancer drugs) are prescribed for short courses, so sales volumes are low.

How can we get new drugs?

Pharma companies need the economic incentives to restart research and development – particularly since new drugs will probably be kept in reserve, for use when everything else has failed. This is where governments and charities could step in. Some already have: the Carb-X fund has committed $550m for research into antibacterial treatments.

Jim O’Neill proposed a $40bn global fund to subsidise the development of new antibiotics. It seemed like a lot of money when he published his review in 2016, but Covid-19 has pushed such concerns into the mainstream; and, given the cost to the world economy of the pandemic, $40bn sounds like a steal.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earring lost at sea returned to fisherman after 23 years

Earring lost at sea returned to fisherman after 23 yearsfeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

Bully XL dogs: should they be banned?

Bully XL dogs: should they be banned?Talking Point Goverment under pressure to prohibit breed blamed for series of fatal attacks

-

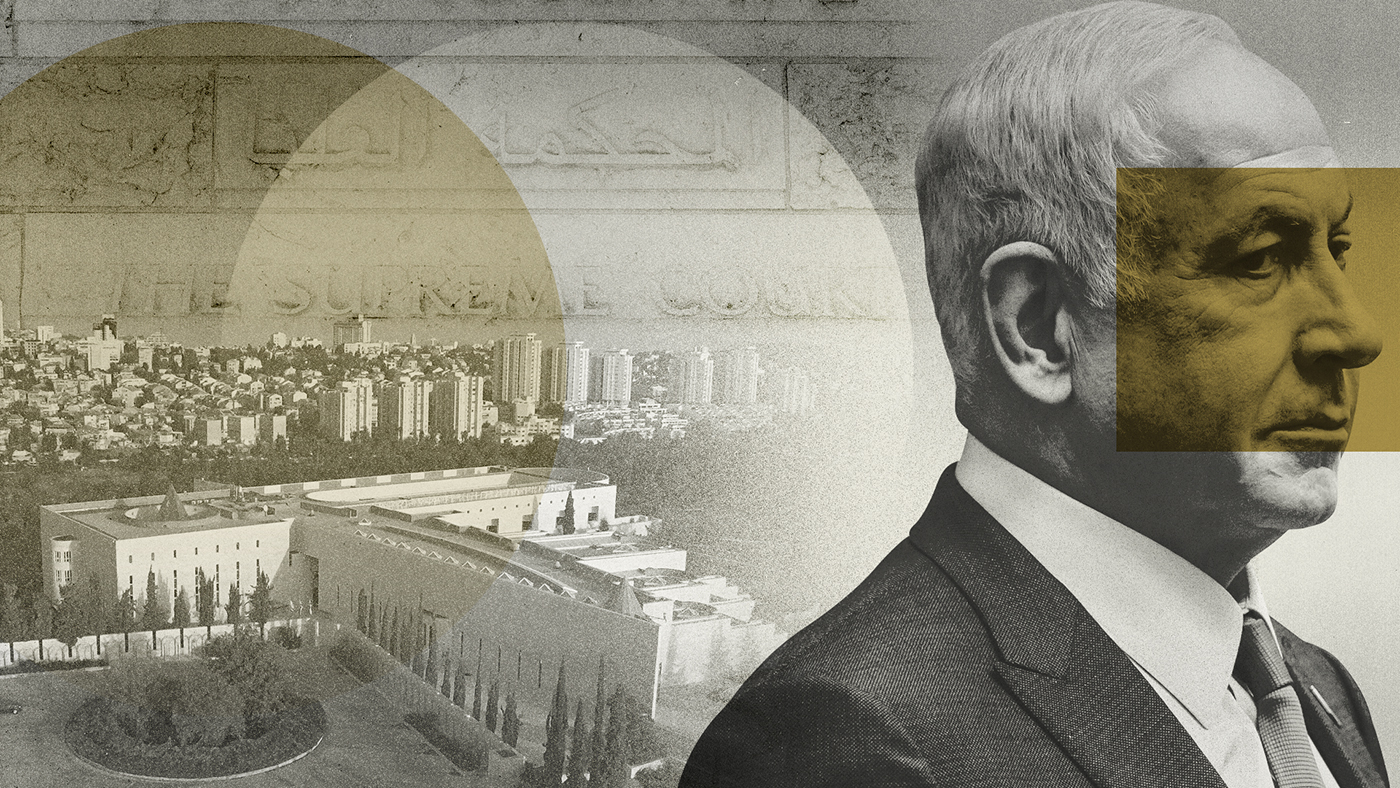

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?

Netanyahu’s reforms: an existential threat to Israel?feature The nation is divided over controversial move depriving Israel’s supreme court of the right to override government decisions

-

Farmer plants 1.2m sunflowers as present for his wife

Farmer plants 1.2m sunflowers as present for his wifefeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?

EU-Tunisia agreement: a ‘dangerous’ deal to curb migration?feature Brussels has pledged to give €100m to Tunisia to crack down on people smuggling and strengthen its borders

-

Manchester alleyway transformed into a plant-filled haven

Manchester alleyway transformed into a plant-filled havenfeature Good news stories from the past seven days

-

China’s ‘sluggish’ economy: squeezing the middle classes

China’s ‘sluggish’ economy: squeezing the middle classesfeature Reports of the death of the Chinese economy may be greatly exaggerated say analysts

-

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Nato

Non-aligned no longer: Sweden embraces Natofeature While Swedes believe it will make them safer Turkey’s grip over the alliance worries some