Why the undersea cables connecting the world are under threat

The global network is a technological marvel – but is also very vulnerable

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Conflicts in Europe and the Middle East risk disrupting the undersea network of cables that forms the backbone of global communications.

Much of West and Central Africa was left without internet service last week as operators of several subsea cables reported failures. Foul play was not suspected, but only days earlier, an estimated 25% of internet traffic between Asia, Europe and the Middle East was impacted after four underwater telecoms cables were cut in the Red Sea.

Although Houthi rebels were not "directly responsible" for the damage, said DW, "their attacks have increased the threat to internet connectivity in the region as they make other, similar incidents more likely".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How do the cables work?

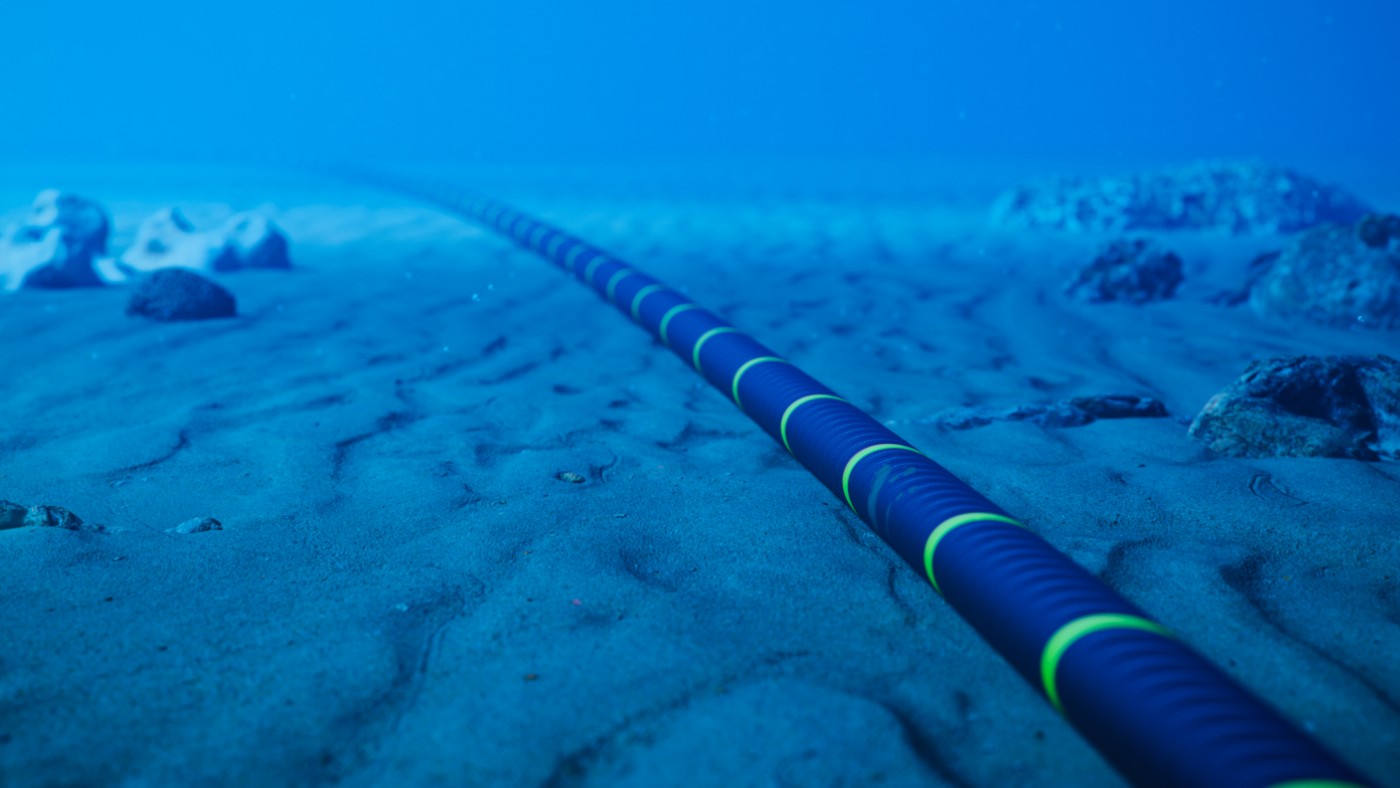

Undersea cables have been used since the 1850s, initially to carry telegrams. Today, fibre-optic cables crossing the sea floor serve as the backbone of the modern internet.

Laid by slow-moving ships, they are typically between two and seven inches thick and have a lifespan of approximately 25 years. Each cable contains fibre threads capable of transmitting data at 180,000 miles per second, wrapped in steel armour, insulation and a plastic coat. Some, such as the Asia-America Gateway cable, which links California to the Philippines and Southeast Asia, stretch more than 10,000 miles in length.

The entire global network of cables is more than half a million miles long, comprising more than 200 independent but interconnected systems, and carrying over 95% of global communications (the rest is done via satellites). In a single day, this network also processes some $10 trillion of financial transfers via the Swift system, which manages global bank transactions.

And the recent explosive growth of cloud computing has vastly increased the volume and sensitivity of data – from military documents to scientific research – crossing these cables.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why are they a subject of concern?

Despite their vital importance to global communications and the flow of money around the world, undersea cables are vulnerable to both accidental damage and deliberate sabotage.

An estimated 100 to 150 cables are severed every year, the vast majority by fishing equipment or anchors. But increasingly, it is the result of hostile action by a nation state. The cables are generally owned and installed by consortia of internet and telecoms companies, without much government oversight. Their locations are usually isolated but publicly known, making them vulnerable to sabotage.

Last year Russia's former president Dimitry Medvedev threatened to destroy undersea cables serving the West, a move that "raises concerns about the potential escalation of cyberwarfare and highlights the vulnerability of critical infrastructure in an interconnected world", said the Daily Express.

This is nothing new. Britain cut five German cables in the First World War, and in the Cold War, the US placed wiretaps on Soviet subsea cables. But the difference now is that any disruption in connectivity could threaten "businesses, governments, and individuals worldwide", said the paper.

The UK is among the most well-connected countries in the world – served by around 60 undersea cables – but it also has "powerful enemies", said The Telegraph. Sabotaged cables could pose "an existential threat" to British security, warned the then backbench Tory MP Rishi Sunak in a 2017 report for the Policy Exchange think tank. "The most severe scenario… of connectivity loss is potentially catastrophic," he added, and even relatively limited damage could "cause significant economic disruption and damage military communications".

In 2022, the head of the UK's armed forces, Admiral Sir Tony Radakin, warned that any attempt to damage "the world's real information system" could be considered an "act of war".

What can be done?

A number of concrete proposals have been put forward. One option is to establish "cable protection zones", which would ban certain types of anchoring and fishing, and require greater disclosure by vessels inside them. Other solutions include updating international law around cables, and establishing treaties that would criminalise foreign interference.

Nato has held exercises to hone potential responses to an attack on infrastructure. So-called "dark cables" – or back-up systems – could also be built to increase resilience in the global network.

But the recent events in the Red Sea suggest the solution may not be in the seas but in the skies. With four underwater cables damaged in the Red Sea earlier this month, satellite operators lent their space-based connectivity to reroute internet traffic, "suggesting that a hybrid system combining underwater and orbital internet might be the best approach moving forward", said Gizmodo.