Qatar 2022: a tainted World Cup?

The most controversial Fifa World Cup yet is ready for kick-off

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Was realising the dream of the Middle East’s first World Cup worth it, asked Andrew England in the FT. “Qatar is about to find out.” The Gulf kingdom has spent $6.5bn on stadiums and facilities and $200bn on infrastructure in order to host the tournament, which kicks off on Sunday. But ever since it was awarded the World Cup by Fifa in 2010, “ceaseless questions” have been asked about the “morality” of the decision.

Within months, allegations of bribery were made against members of Fifa’s executive committee who voted for Qatar. Because of the country’s climate, the tournament had to be moved to the winter, disrupting the football season. Concerns have been expressed about Qatar’s lack of media freedom, its anti-gay laws and its lack of football heritage. Most of all, though, there has been intense scrutiny of the deaths and injuries of migrant workers used for its World Cup mega-projects. One Guardian report (contested by Qatar) found that more than 6,500 migrant workers had died since 2012. The country’s ruling al-Thani family wanted their nation to take its place on the “global stage”; but Qataris didn’t anticipate it becoming “a lightning rod”.

The “inconsistency, selectivity and disproportionality” of Western media coverage has been quite extraordinary, said Emad Moussa on Al Araby. Qatar engaged with its critics in good faith. Between 2017 and 2021, it implemented major changes to its labour system: it introduced a minimum wage and revised the controversial kafala sponsorship system, which meant that migrant workers no longer required the approval of their employers to change jobs. As for wider human rights issues, such concerns did not stop Russia getting the 2018 World Cup, or Beijing the 2008 Olympics, even though both nations have far worse records than Qatar. Follow the logic of the critics, and it appears that unless nations “abide by certain, strictly Western liberal values”, they cannot host major sporting events.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Football, after all, is played in every corner of the world, said Mark Perryman in The Guardian. And the World Cup should celebrate that. This the first Middle Eastern World Cup, and the first in a Muslim-majority country, which is great news. “Love football, not Fifa.” Well, this tournament doesn’t look much like “a joyous celebration of the game”, said The Guardian. It looks more like a “grubby hymn to money and power”. Qatari labour law reforms are superficial, and may not endure. Sixteen of the 22 Fifa committee members who made the 2022 decision have been investigated for corruption or implicated in it. Even Sepp Blatter, Fifa’s former head, says it was a “bad choice”. And it was, said Simon Kuper in the FT. But it will go ahead even so, and we might as well make the most of it. “It can at least bring joy, shine a spotlight, perhaps prompt compensation for migrants and embarrass sports organisations out of ever choosing a host like Qatar again.”

Why was the choice of Qatar so controversial?

In December 2010, the Fifa president at the time, Sepp Blatter, announced the shock decision to award the world’s biggest sporting tournament to Qatar. Selected over the US, South Korea, Japan and Australia, it will be the smallest nation ever to host the event, with a population of 2.8 million (and just over 330,000 citizens). Qatar’s team had never qualified for a World Cup, and the country had no discernible footballing tradition. It had no suitable stadiums either, which meant that eight venues had to be upgraded or built from scratch. The tournament could not reasonably be played in the summer, when temperatures average around 40°C. So instead it will take place in the cooler months of November and December, disrupting most of the world’s domestic football competitions. Qatar is also an absolute monarchy, with a poor human rights record; and it has often been criticised for exploitative labour practices and dangerous working conditions.

So how did it win the bid?

Ever since 2010, accusations of corruption have swirled around the 2022 bidding process. It was alleged that the disgraced Fifa vice president Jack Warner and his family were paid $2m by a company linked to Qatar’s campaign. In 2014, The Sunday Times published a cache of documents it said were proof of Qatar’s plot to “buy the World Cup” – allegedly orchestrated by Mohamed bin Hammam, a former Fifa vice president and the country’s top football official. It is said that $5m (£3m) was paid to Fifa officials in return for their support. Bin Hammam and those accused of accepting bribes deny the charges, but broader anti-corruption investigations against Fifa followed; nearly 30 people have been convicted as a result of a US department of justice probe. Blatter and his former colleague Michel Platini were forced out of their jobs, and were indicted on fraud charges.

What criticisms were made over working conditions?

Qatar relies heavily on migrant labourers, who make up 95% of its workers. Over the past decade, tens of thousands of workers, mostly from the Indian subcontinent, have built World Cup infrastructure ranging from stadiums to new hotels to transport systems. They were largely employed using the kafala or sponsorship system, under which visas are obtained by specific Qatari employers – meaning that, until recently, if workers wanted to change jobs, or even leave the country, they needed their employer’s permission. This system was ripe for abuse; at its worst, it has been described as akin to slavery. Amnesty International has detailed extensive maltreatment of foreign workers, including forced labour; salaries being underpaid; cramped and dirty accommodation; and workers being threatened if they complain. Working conditions are also reportedly often unsafe.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Unsafe in what ways?

In February last year, The Guardian compiled figures from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka and found that more than 6,500 migrants from those countries had died in Qatar since 2010. In particular, there have been reports of labourers who worked for World Cup projects dying and suffering serious injury because of heat stroke after working in sweltering conditions. Studies have found increased rates of chronic kidney disease among Nepali migrant workers returned from Qatar, linked to working long hours in summer with insufficient drinking water. Some of these workers will now require dialysis several times a week for the rest of their lives.

How did the sport respond?

Several countries registered concerns over Qatar’s human rights record. The most vocal opposition was in Norway, whose players wore T-shirts bearing slogans such as “Human rights, on and off the pitch” ahead of qualifying games. Countries including Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands took similar steps. Yet the condemnation has been by no means universal, and many appear ready to cash in on the tournament; David Beckham signed a £150m deal to be an ambassador for the tournament.

What is Qatar’s position?

It denies that bribes were paid to secure votes for the right to host the tournament. Qatar also contests the high number of migrant labourer deaths; it says that there have been only 37 deaths among workers directly linked to construction of World Cup stadiums. Under pressure, in 2019 it reformed the kafala system, so that legally migrants can change jobs or leave the country without their employer’s permission; and it has introduced a minimum wage. The UN’s International Labour Organisation declared that these reforms mark “the beginning of a new era for the Qatari labour market”.

What will the event’s legacy be?

Blatter has since described the decision to give Qatar the World Cup as a “mistake” – but it will go ahead even so. Fifa and Qatar insist that the tournament will leave a lasting social legacy. Critics argue this will be skin deep: that many employers ignore the new laws; and point out that though LGBTQ+ fans are in theory welcome, homosexuality remains illegal. Despite all the controversy, Qatar still stands to benefit, said Nicholas McGeehan of the human rights group FairSquare. “For every fan who is concerned about migrant workers and LGBT issues, there are probably another 40 or 50 people who are uncritically consuming PR content that presents Qatar as a luxurious destination with five-star hotels and camel rides.”

The transformation of Qatar

A former British protectorate which gained independence in 1971, Qatar has been dominated by the Al Thani family since the mid 19th century. Like much of the region, it was changed profoundly by the discovery of oil, in 1939. Today it is the world’s largest producer of liquefied natural gas, and one of the richest countries per capita on Earth – home to an ever increasing number of gleaming skyscrapers, cultural attractions and global university outposts. It has sought to cultivate a reputation for openness: the TV network Al Jazeera, founded in Doha in 1996, has shaken up the Arab world by taking its leaders to task. The station, though, seldom criticises Qatar; in fact, criticism of the Qatari government is illegal.

The emir, Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, holds all executive power. In October last year, however, Qataris elected 30 members of a consultative council for the first time. Only those whose families lived in Qatar before 1930 were allowed to vote. Qatari relations with other Gulf states have often been strained in recent years: the UAE, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia have accused it of supporting terrorism, notably the Muslim Brotherhood, and imposed a damaging trade embargo for three years. Diplomatic ties were restored last year.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

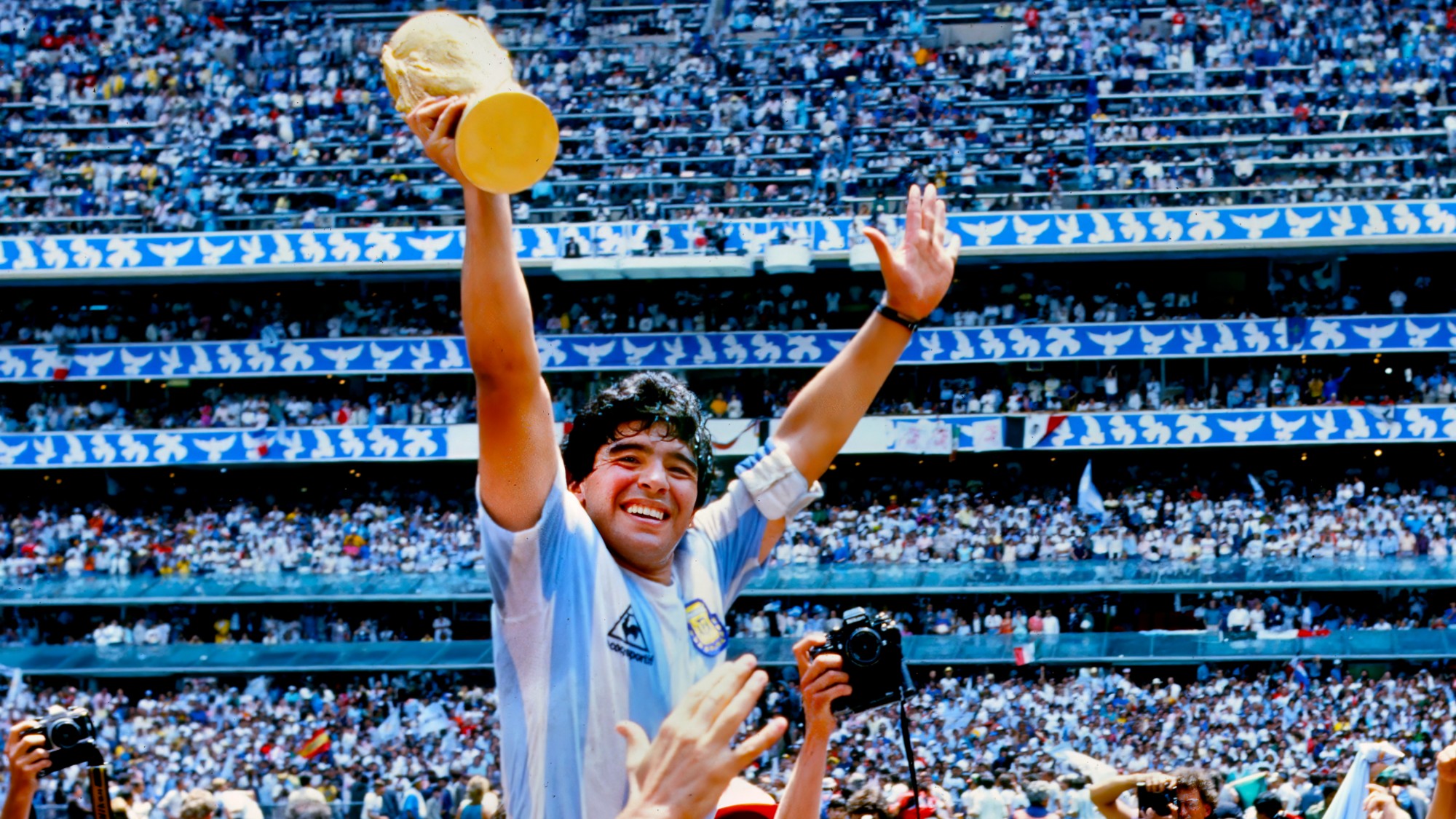

Five years after his death, Diego Maradona’s family demand justice

Five years after his death, Diego Maradona’s family demand justiceIn the Spotlight Argentine football legend’s medical team accused of negligent homicide and will stand trial – again – next year

-

Will 2026 be the Trump World Cup?

Will 2026 be the Trump World Cup?In the Spotlight US president already using the world’s most popular football tournament to score political points

-

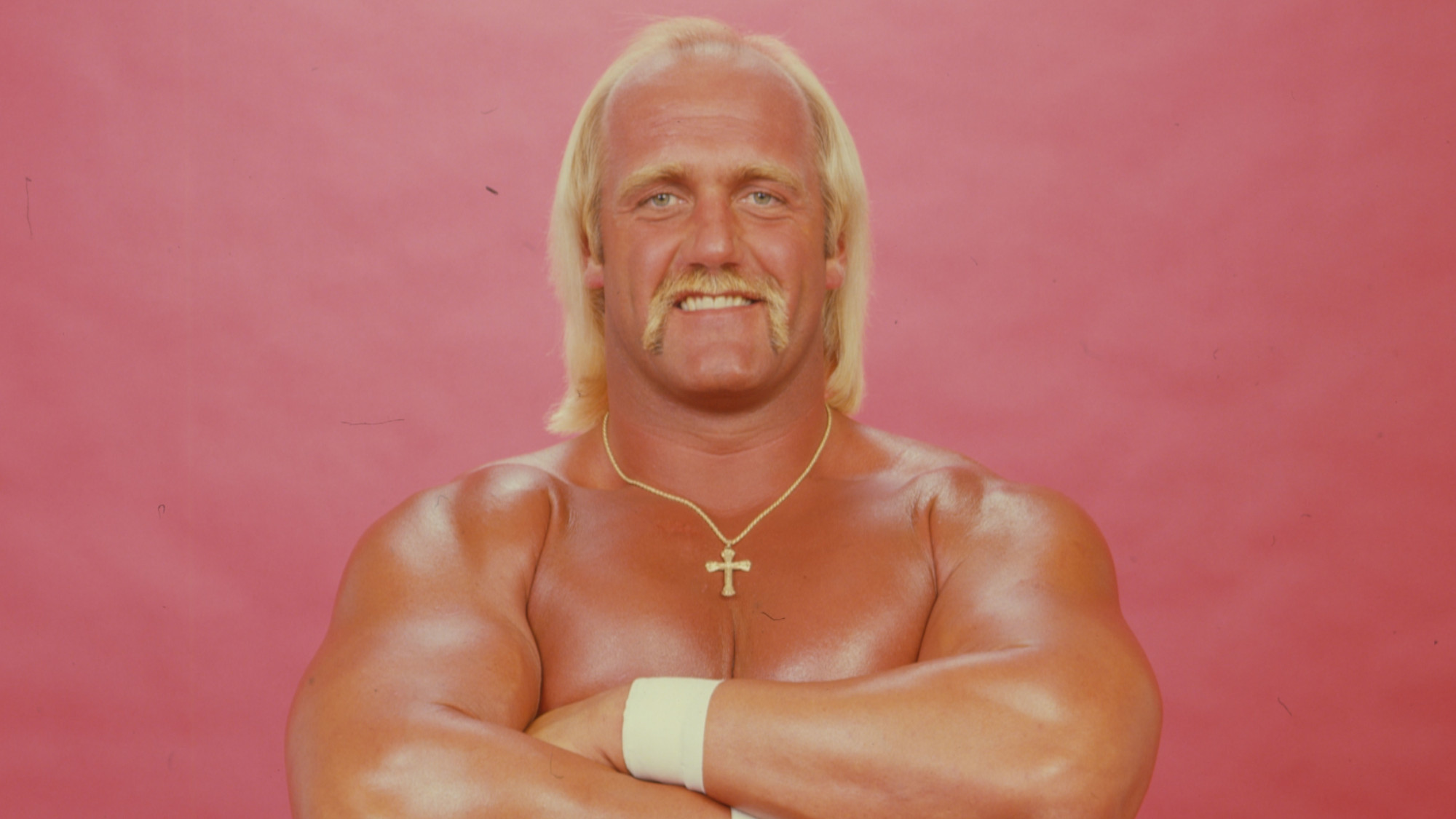

Hulk Hogan

Hulk HoganFeature The pro wrestler who turned heel in art and life

-

World Cup 2026: uncertainty reigns with one year to go

World Cup 2026: uncertainty reigns with one year to goIn the Spotlight US-hosted Fifa tournament has to navigate Trump's travel bans, logistical headaches and an exhausting expanded format

-

Cricket's crackdown on 'monster' bats

Cricket's crackdown on 'monster' batsIn the Spotlight Indian Premier League has introduced on-pitch checks to ensure bats meet strict size limits

-

The Masters: Rory McIlroy finally banishes his demons

The Masters: Rory McIlroy finally banishes his demonsIn the Spotlight McIlroy's grand slam triumph will go down as 'one of the greatest and most courageous victories in the history of golf'

-

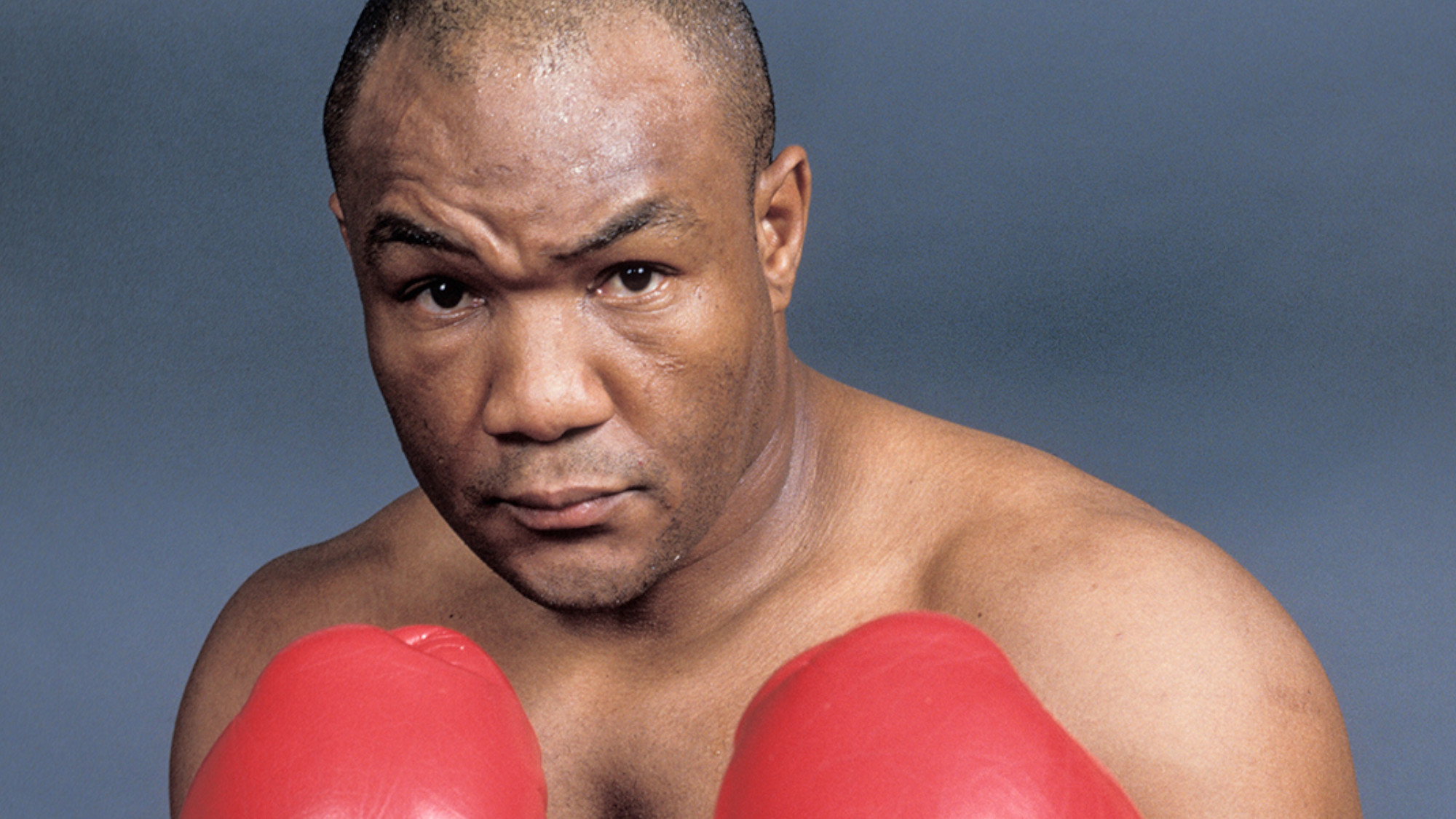

George Foreman: The boxing champ who reinvented home grills

George Foreman: The boxing champ who reinvented home grillsFeature He helped define boxing’s golden era