Paralympics: Classifications and unusual sports explained

At the Rio 2016 Paralympics there will be 22 sports – some have been adapted and others, like goalball, are unique

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Paralympics finally kick off tomorrow after a troubled build-up. Rio's second bout of sports, which runs from September 7 to 18, has been blighted by several setbacks, including sluggish ticket sales, the exclusion of the Russian team over state-sponsored doping and a funding crisis that has seen money allocated to the Paralympics reportedly diverted to the Olympics.

This week has also seen a row over classifications, with claims that some athletes lie about their disabilities in order to increase their medal chances.

However, with more funding secured and the Brazilian public starting to take notice there is a mood of "cautious optimism" in Rio, says Jacob Steinberg of The Guardian.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The organisers will be hoping that once the Games begin it will be the athletes rather than the off-field distractions that do the talking.

However, the Games do feature unfamiliar sports and confusing categories, which can make it hard for spectators to follow them. Here's a guide:

CLASSIFICATIONS

Classifications are designed to create a level playing field for athletes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The system "divides the athletes of a given sport into classes, which ensures that an athlete or team competes under equal conditions against their adversaries", explains the Rio 2016 website.

Athletes are divided into categories, based on the extent of their disability. At the broadest level these break down into three groups: physical, visual and intellectual.

Within those wider groups there are sub-divisions – in total there are ten different impairments that are taken into account – and because each different sport has its own unique physical demands, each has its own set of classifications.

All athletes must be assessed before being given a category.

In athletics, for example, the nature of the disability is numbered and preceded by either a T for track or F for field.

- Those in classes 11 to 13 are visually impaired.

- Class 20 events are for those with intellectual disabilities.

- Athletes in classes 31 to 38 have cerebral palsy or other conditions that affect muscle co-ordination and control. Some are seated, others standing.

- Those in class 40 are affected by dwarfism.

- [Classes 42 to 46 are for amputees. In class 42 to 44 the legs are affected and in 45 and 46 the arms.

- Classes 51 to 58 are for wheelchair athletes. Track events finish at class 54, but the field events continue.

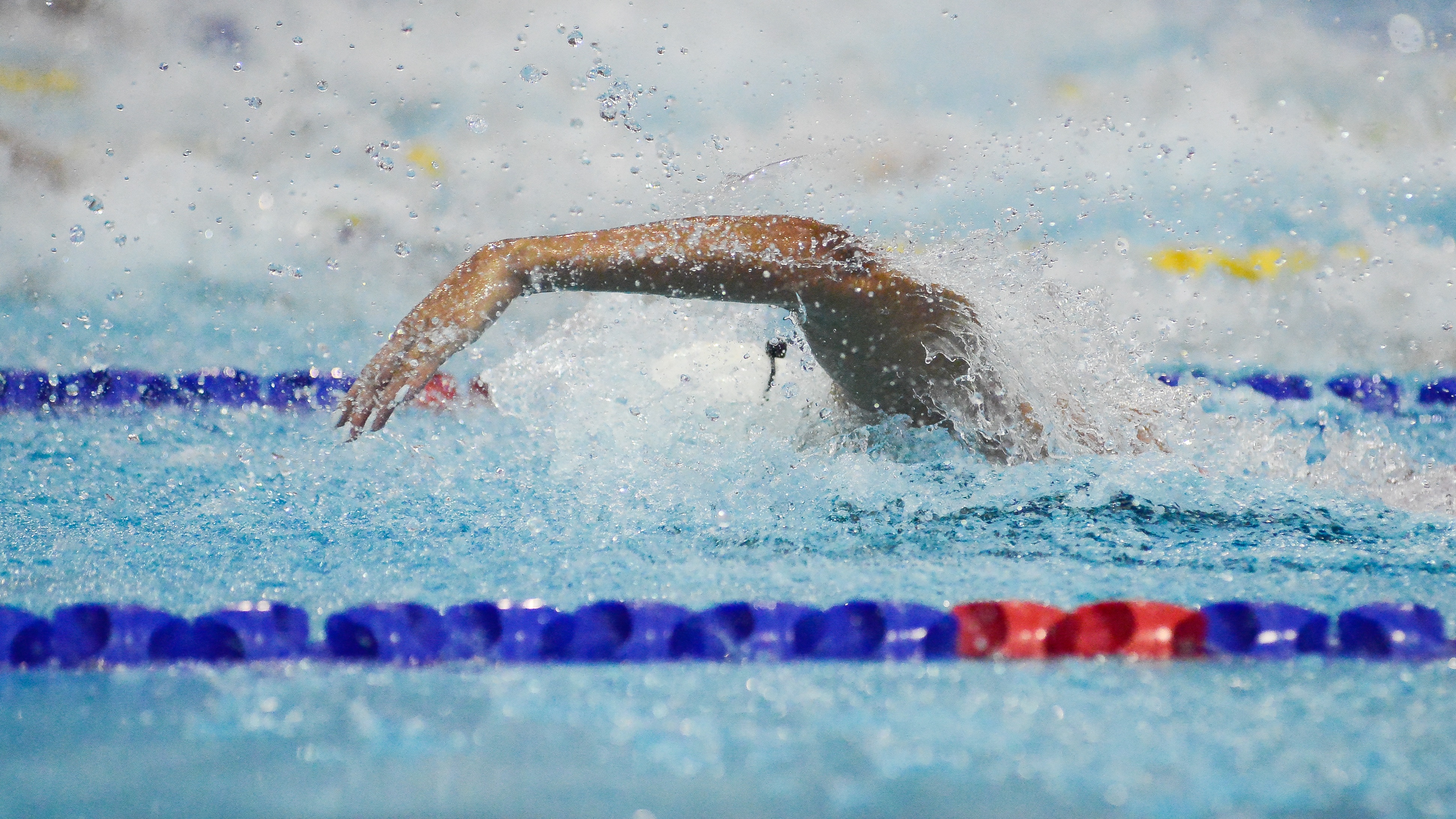

Other sports have their own classifications. Swimming uses the prefix S (SB for breaststroke and SM for medley events) and has far fewer classifications for those with physical disabilities, which has led to some controversy in the lead-up to the games.

Like track and field it uses classes 11 to 13 for those with visual disabilities. But those with intellectual disabilities compete in class 14 (rather than 20 as in athletics).

Those with physical disabilities are in classes numbered one to ten, and competitors with different disabilities will compete against each other. So Ellie Simmonds will be competing in the S6 and SB6 categories as she has dwarfism. But she will be up against competitors with cerebral palsy and amputees.

Cycling has four classes for people using handcycles, H1 to H4. There are two classes, T1 and T2, for those on tricycles, and bicyclists compete in five categories from C1 to C5.

The other 19 sports that make up the Paralympics have their own classifications, outlined by the BBC, but the aim in each event remains the same – to ensure that competition is fair.

SPORTS

Many sports, like athletics, swimming and cycling, are fundamentally the same for Paralympians as for able-bodied athletes, but others have been tweaked to allow disabled athletes to take part.

Blind football is a game played on a hard surface between two teams of five with a ball filled with ball bearings, for example. There are boards around the pitch to help amplify the sound and the crowd must remain silent so the blindfolded players can hear each other and their opponents.

Seven-a-side football is played by athletes with cerebral palsy or brain injuries. Players from different disability classifications play together but there are restrictions on how many players from each classification can be on the field at the same time.

Wheelchair rugby was developed in Canada in the 1970s. It was originally given the gruesome name murderball and is not for the fainthearted. Two teams of four players fight each other to get the ball into their opponents' goal area. Collisions between wheelchairs are part and parcel of the game and veteran GB player Troye Collins summarised the sport like this: "Get the ball to the other end of the gym and score as many points as you can by beating the crap out of everyone."

In sitting volleyball the competitors sit on the floor and part of an athlete's body must remain in contact with the floor whenever a shot is attempted. The net is just over a metre high.

Powerlifting is the Paralympic equivalent of weightlifting, but competitors only perform a bench press.

There are also two sports that are unique to the Paralympics: boccia and goalball.

Boccia is closely related to bowls and features some of the most disabled athletes in the Games. The aim is to get a ball as close as possible to a jack. Some of the competitors use ramps as they are unable to throw the ball.

Goalball, developed by soldiers injured in World War II, is played by two teams of three blind and visually impaired athletes who hurl a ball filled with bells towards a goal at the far end of the court, which is guarded by the opposition. As with blind football, the crowd must remain silent. It is one of the most exciting team sports to feature at the Games.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Paralympics: can Team USA turn things around for Los Angeles 2028?

Paralympics: can Team USA turn things around for Los Angeles 2028?Today's Big Question Beijing and London offer model for how hosting can lead to medal success as China maintains dominance

-

Will a death at the CrossFit Games change the sport?

Will a death at the CrossFit Games change the sport?Today's Big Question CrossFitter Lazar Dukic drowned during a competition earlier this month

-

The 'Enhanced Games': a dangerous dosage?

The 'Enhanced Games': a dangerous dosage?Talking Point A drug-fuelled Olympic-style competition is in the works but critics argue the risks are too high

-

Swimming’s governing body bans trans athletes from elite women’s races

Swimming’s governing body bans trans athletes from elite women’s racesTalking Point Fina may introduce an ‘open’ category to allow trans swimmers to compete at highest level

-

Britain’s greatest Paralympian: cyclist Sarah Storey

Britain’s greatest Paralympian: cyclist Sarah StoreyIn the Spotlight Her achievements are ‘off-the-scale extraordinary’

-

Timeline: a history of the Paralympics

Timeline: a history of the Paralympicsfeature Starting this week in Tokyo, the Paralympic Games has its origins in post-war Britain

-

Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games guide: opening ceremony, sports, venues and UK TV details

Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games guide: opening ceremony, sports, venues and UK TV detailsIn Depth 4,350 athletes will compete across 22 sports in Japan’s capital city

-

Pool party: golden ‘new era’ for British swimming

Pool party: golden ‘new era’ for British swimmingfeature Team GB swimmers made a splash at the Tokyo Olympics