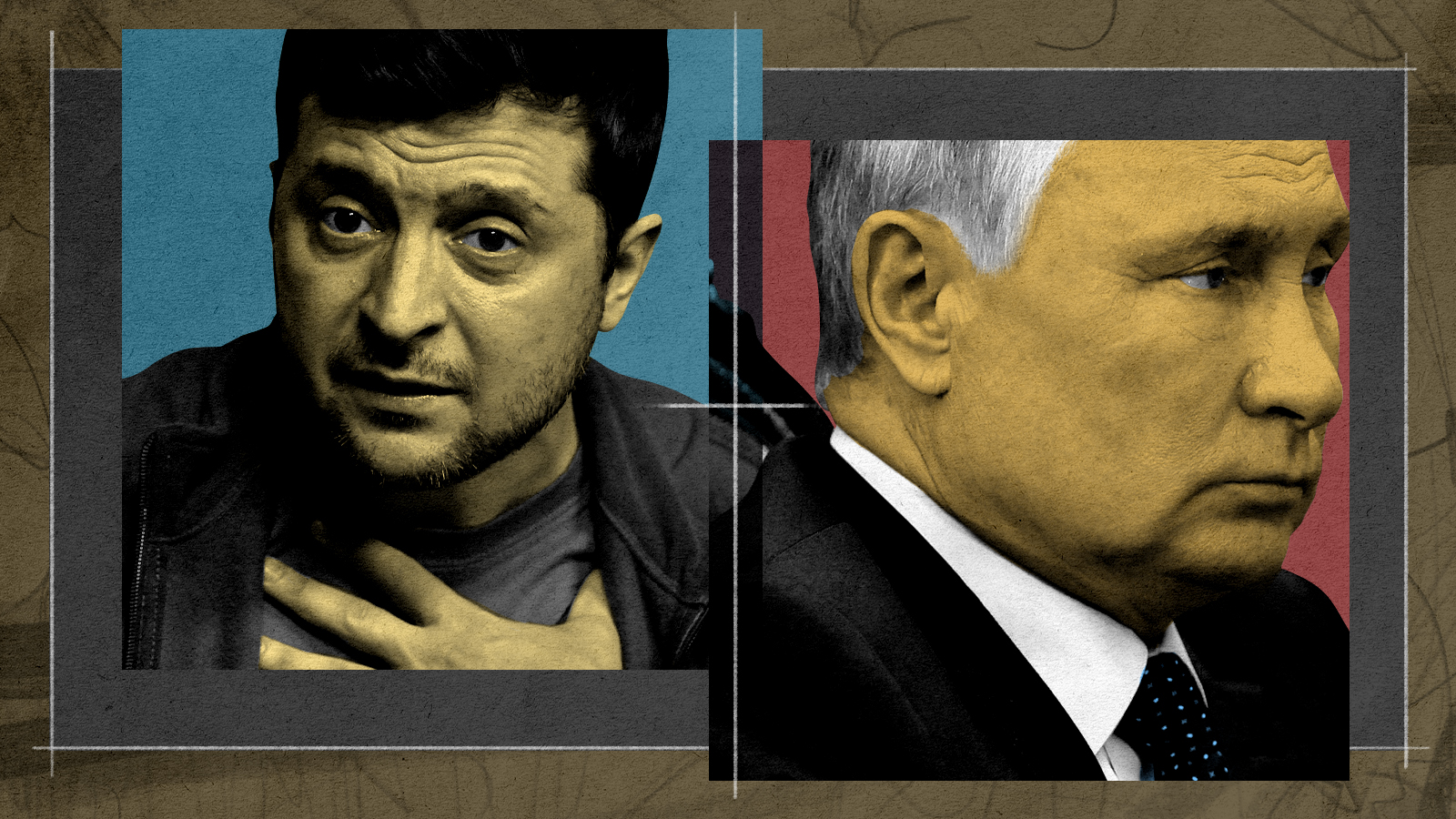

Peace in Ukraine is worth Putin's price

Why Zelensky should have taken Putin up on his deal

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said Monday that Russia would cease all military operations if Ukraine agreed to four demands.

The demands were: stop fighting, formally cede Crimea to Russia, recognize the independence of the Russian-backed separatist republics in eastern Ukraine, and amend the Ukrainian constitution to forbid membership in international blocs like NATO and the European Union.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky responded that he would not accept Russia's "ultimatum." This was a mistake.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

To be clear, when I say Zelensky should accept Russian President Vladimir Putin's deal for the sake of the Ukrainian people, I'm not blaming Zelensky for the suffering Ukraine will endure if it fights on. Ukraine is the victim here. If Zelensky rejects the deal and Putin keeps bombing civilians, that's not Zelensky's fault. He didn't kill those people. But Zelensky still has the responsibility to do what's best for his country given the realities of the situation.

American hawks — from lawmakers and foreign-policy experts to randos on Twitter — seem to think the war in Ukraine is some kind of Marvel movie in which the only acceptable outcome is good guys win, bad guys lose. They puff out their chests and pontificate about the valiant Ukrainian people fighting to the last man. Question them, and they'll start making noises about Neville Chamberlain and "appeasement."

What they fail to understand is that "appeasement" is when you accede to demands in order to avoid conflict. It shows the bully he can have whatever he wants without risking his own skin. If Zelensky had made the deal before the invasion, that would be appeasement. But he didn't.

The Russians attacked, and Ukraine has given them one hell of a bloody nose. Doomers who expected Kyiv to fall within 72 hours have been proven wrong. Putin's war goals, as originally stated, were to "demilitarize and de-Nazify" Ukraine, both of which implied installing a puppet regime. That he appears to have abandoned these ambitions is a testament to the strength of Ukraine's current position.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

At the same time, it would be a mistake overestimate how strong that position is or how long it will stay that way. The Ukrainian military is badly outnumbered and outgunned. Kharkiv and Mariupol may fall within days. A NATO no-fly zone isn't going to happen. Despite Ukraine's stalwart resistance, the likeliest outcome by far is still a Russian victory.

There is no scenario in which Putin admits defeat, surrenders his claims on Crimea and the Donbas, and withdraws with his tail between his legs. Like all autocrats, he can't afford to appear weak. Putin needs a win, and he'll get it by any means necessary. The Russian response to stronger-than-anticipated Ukrainian resistance will not be to give up. It will be to kill as many civilians as possible in an attempt to break Ukraine's spirit. We already see this happening. Wilson Center fellow Kamil Galeev writes that Russia is "going full Syria mode" in Ukraine, referring to the "indiscriminate carpet bombing" in which Russia engaged during its intervention in the Syrian Civil War. Ukrainian sources claim more than 2,000 civilians have already been killed.

Ukraine has nothing to gain by continuing to fight. During an appearance on MSNBC, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton admitted that Kyiv is likely to fall and said the "model" moving forward should be the Afghan insurgency against Soviet occupation in the 1980s. It's true that, as Clinton said, it "didn't end well for the Russians," but it also didn't end particularly well for Afghanistan, which suffered up to two million civilian deaths and was destabilized for decades to come. No one should want that for Ukraine.

Once this reality has been accepted, the only question remaining is whether any of Russia's demands are non-starters.

The first of two common objections I've seen is not to any aspect of the deal but to the very idea of making a deal with the Russians. Putin, the argument goes, cannot be trusted and therefore cannot be negotiated with. Just look at the Russians' refusal to honor even temporary ceasefire agreements.

But while Putin cannot be trusted to do what is right, he can be trusted to act in his own self-interest. Breaking the ceasefires was in Putin's self-interest because it enabled his troops to kill more civilians. Claiming that he broke the ceasefires because Ukrainian forces compelled civilians to remain in the cities was in his self-interest because it helped push the narrative that Ukraine's leaders are using civilians as human shields.

This agreement would be in Putin's self-interest because it would allow him to save face, restore his country's sanctions-ravaged economy, and avoid a long, bloody insurgency. To rule out negotiation is to insist on unconditional surrender, which is both wildly unrealistic and will only increase suffering.

The second is that, if Ukraine surrenders territory and rules out joining NATO, Russia will just invade again in a few years. Even if that were the case, Ukraine should still take the deal. If the worst-case scenario is the same as the status quo, what is there to lose? But there's no guarantee Russia would attack again. Anatol Lieven of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft points out that, during the Cold War, Finland, and Austria maintained the same neutral status Russia wants from Ukraine. Both countries remained free, prosperous, and democratic.

As for Crimea and the Donbas, Ukraine would be wise to admit they're gone for good. Putin won't relinquish Russian claims on those territories, and any idea of retaking them by force is a pipe dream. If Putin hadn't forced Ukraine to cede that land, NATO would have. There's no way the alliance would admit a member with active claims on Russian-occupied territory. That's just asking for World War III.

Maybe we'd all love to see Ukrainian tanks rolling into Sevastopol and Putin being carted off in chains to The Hague. But politics is the art of the possible. The deal on the table is a good one. Zelensky would remain in power, Ukraine would keep almost all its territory, and the killing would stop.

Fighting to the bitter end to stop Russia from overthrowing Ukraine's elected government would have been brave and fitting. To do so with an off-ramp like this available is much harder to justify.

Zelensky rejected Putin's ultimatums, but he didn't close the door entirely. "[W]e have the possible solution, resolution for these three key items," Zelensky told ABC News, as long as Putin is willing to "start talking" in earnest.

For the sake of the Ukrainian people, let's hope he means it.

Grayson Quay was the weekend editor at TheWeek.com. His writing has also been published in National Review, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Modern Age, The American Conservative, The Spectator World, and other outlets. Grayson earned his M.A. from Georgetown University in 2019.

-

Elon Musk’s pivot from Mars to the moon

Elon Musk’s pivot from Mars to the moonIn the Spotlight SpaceX shifts focus with IPO approaching

-

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Magazine solutions - February 20, 2026

Magazine solutions - February 20, 2026Puzzle and Quizzes Magazine solutions - February 20, 2026

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guarantee

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guaranteeTalking Points Zelenskyy says it is a requirement for peace. Will Putin go along?

-

Vance’s ‘next move will reveal whether the conservative movement can move past Trump’

Vance’s ‘next move will reveal whether the conservative movement can move past Trump’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Will there be peace before Christmas in Ukraine?

Will there be peace before Christmas in Ukraine?Today's Big Question Discussions over the weekend could see a unified set of proposals from EU, UK and US to present to Moscow

-

Ukraine and Rubio rewrite Russia’s peace plan

Ukraine and Rubio rewrite Russia’s peace planFeature The only explanation for this confusing series of events is that ‘rival factions’ within the White House fought over the peace plan ‘and made a mess of it’

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Push for Ukraine ceasefire collapses

Push for Ukraine ceasefire collapsesFeature Talks between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin were called off after the Russian president refused to compromise on his demands