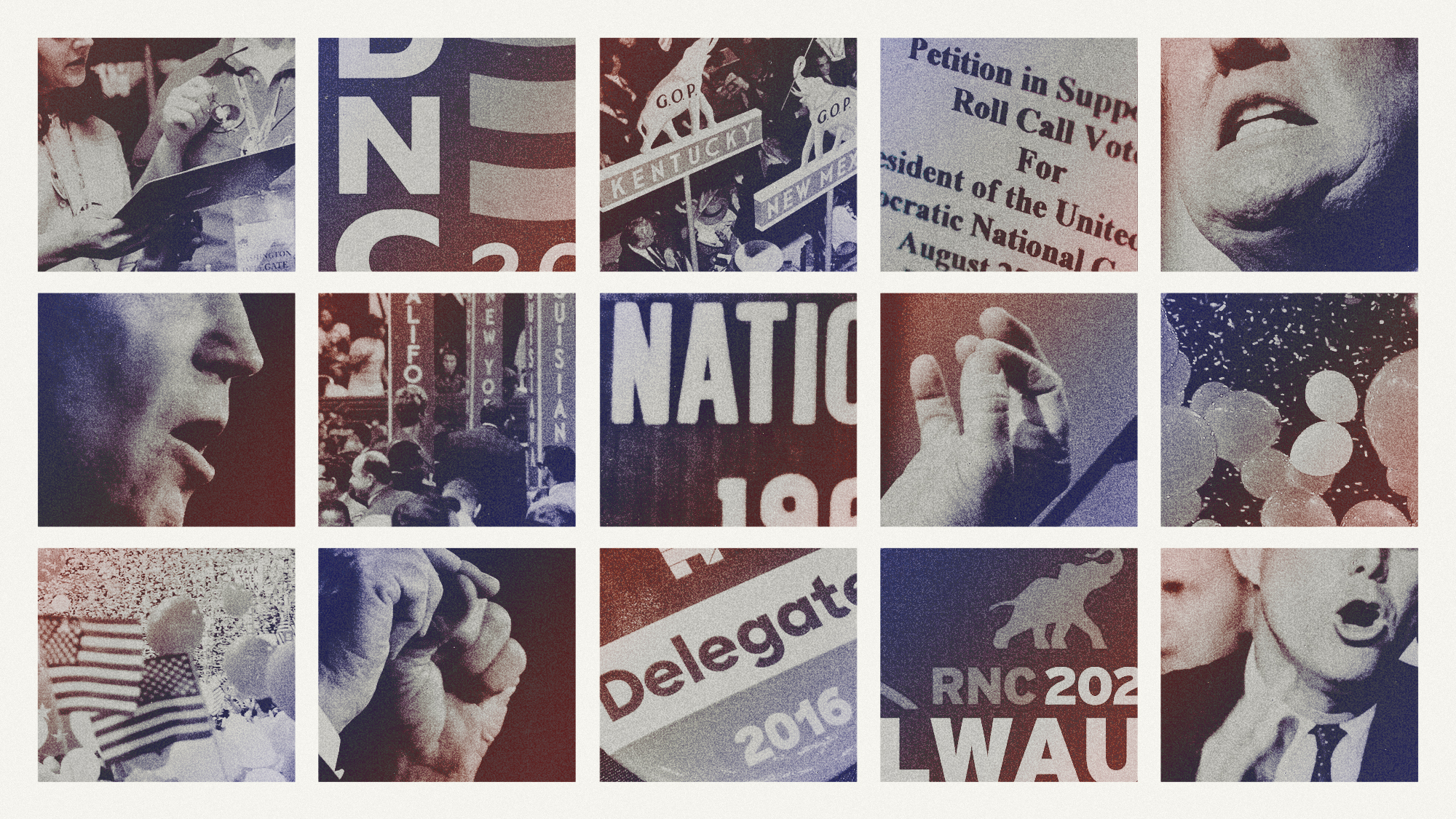

How do political conventions work?

The process of choosing a party's nominee has several moving parts

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With the 2024 presidential election months away, both the Democrats and the Republicans will soon crown their nominees at their respective conventions: the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee.

However, selecting a nominee has not always been a straightforward path in years past. From the 1968 Democratic Convention which was wrought with violence over the Vietnam War to the highly contested 1940 Republican Convention, the process has often been far from a straight line. How do the Democratic and Republican conventions work, and what are their major differences?

What happens at each convention?

The conventions occur when delegates for the respective parties gather to formally vote on and nominate a candidate for the general election. In general, the conventions "deal with the typically boring orders of business: approving credentials, approving the platform, and approving the rules," said the Brookings Institution.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The most notable highlight of the conventions are speeches given by various members of the party. This often includes former presidents, first ladies, well-known governors, and the presumptive presidential and vice presidential nominees. Following this comes the "actual roll call of delegates casting ballots for their party's nominee(s) for president and vice president," said the Brookings Institution, a process that continues until a candidate garners the necessary number of votes to become the nominee.

The delegates themselves are "individuals who represent their state or community at their party's presidential nominating convention," said The Associated Press. There are generally two types of delegates: pledged and unpledged (also referred to as superdelegates). Pledged delegates "must vote for a particular presidential candidate at the convention based on the results of the primary or caucus in their state," said the AP, while unpledged or superdelegates "may support any presidential candidate regardless of the primary or caucus results in their state or local district." In general, pledged delegates are legally bound to vote for a specific candidate "at least through the first round of voting at the convention," after which, depending on party rules, some pledged delegates "become free to vote for any candidate on subsequent rounds of voting."

What are the differences between the two conventions?

While the mechanisms of the conventions are similar, there are a few differences, mainly in how the delegates are actually awarded to candidates. In the Democratic Party, candidates are "generally awarded delegates on a proportional basis," said the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). For example, a candidate "who receives one-third of the vote or support in a given primary or caucus receives roughly one-third of the delegates." That's been the case ever since a change in the 1970s that gave more power to primary elections in selecting a presidential nominee, following the chaotic 1968 convention where party leaders ignored primary results.

In the Republican Party, though, rules are more varied, said the CFR. Some states "award delegates on a proportional basis, some are winner-takes-all, while others use a hybrid system." Previous GOP election cycles even "awarded no delegates and were intended only to assess the preferences of the party faithful," though these so-called "beauty contests" were scrapped following rule changes in 2016.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Democratic Party also has another element that could play a role in a contested convention: the aforementioned unpledged delegates or "superdelegates." While the Republican Party's superdelegates make up only a small amount of their total delegates, the Democratic Party's superdelegates include "not only members of the national committee, but all members of Congress and governors, former presidents and vice presidents, former leaders of the Senate and the House, and former chairs of the Democratic National Committee," said the CFR. This makes them more influential for the Democrats; In 2016, superdelegates represented about 15% of the total convention delegates.

However, superdelegates led to significant controversy that year, partially due to a perception that they cost Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) the nomination, and Democrats responded by altering their rules to reduce the power of superdelegates. Beginning with the 2020 election, Democratic superdelegates are no longer allowed to participate in the first round of ballot voting, and can only vote in subsequent rounds of a contested convention.

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rolls

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rollsSpeed Read A Trump-appointed federal judge rejected the administration’s demand for voters’ personal data

-

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train army

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train armySpeed Read Trump has accused the West African government of failing to protect Christians from terrorist attacks

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders

-

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax