The short history of TV debates and UK general elections

Keir Starmer has described them as 'part and parcel of the election cycle now' but their format has constantly changed

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Keir Starmer has said he will take part in TV election debates but won't commit to the idea of weekly head-to-heads suggested by Rishi Sunak.

Starmer told BBC Breakfast that he could debate with the PM "once or a hundred times", but "I know what he is going to say. He will say everything is fine… we hear that every week at PMQs".

Sunak last week challenged Starmer to take part in six TV debates, tackling issues like tax, the cost of living and security. But Labour said Starmer would not agree to "tearing up" the format established in previous elections "just to suit this week's whims of the Tory party".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Labour leader also told Sky News that "of course there are going to be TV debates". They are "part and parcel of the election cycle now".

How long have we had TV debates?

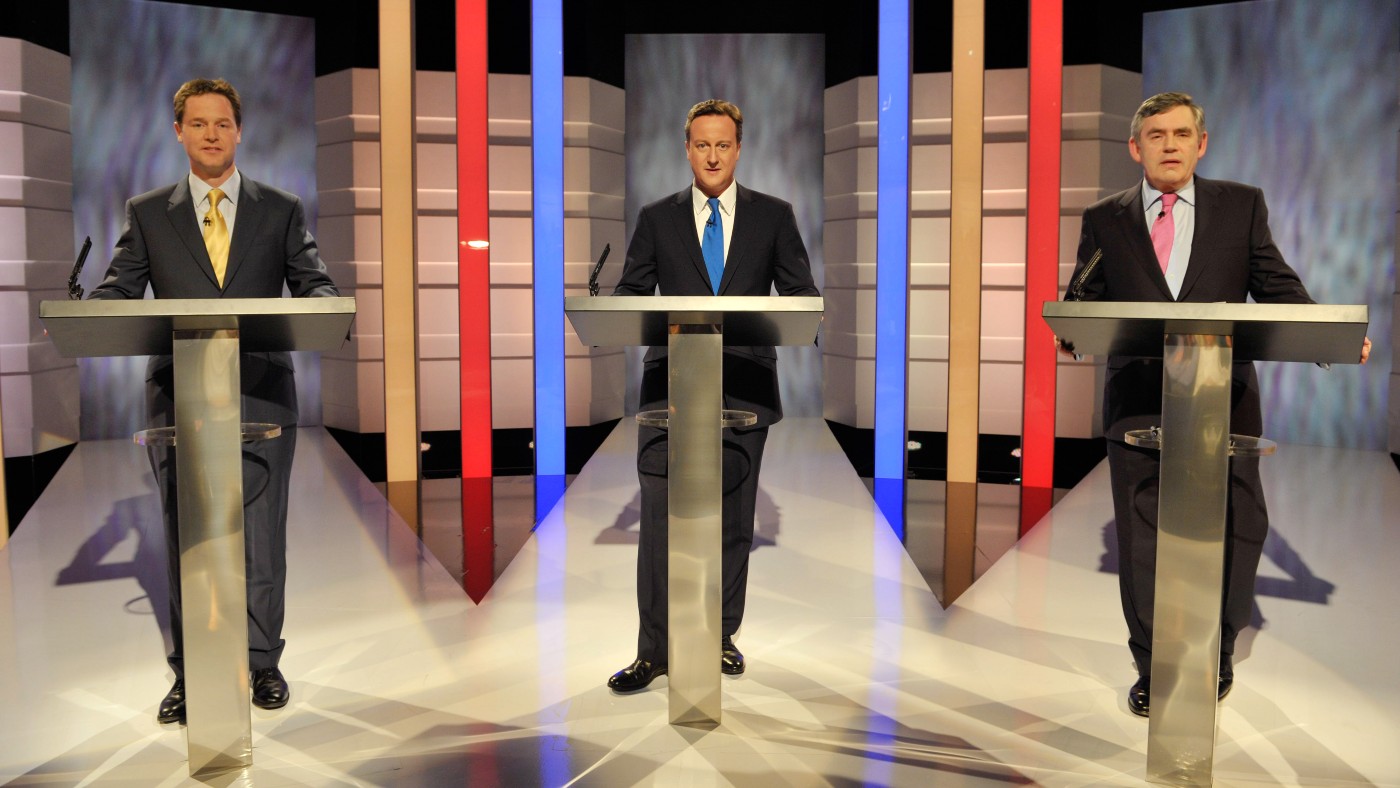

Although a staple of US politics since the 1950s, the first TV debates in the UK didn't take place until the 2010 general election. Before then "the UK was considered unusual in developed democracies in not holding televised debates", said UK parliamentary historian Neil Johnston for the House of Commons Library. In 2010 there were three debates, featuring the Labour prime minister Gordon Brown, Conservative leader David Cameron and Nick Clegg from the Liberal Democrats.

Although there were complaints that the debates in 2010 dominated the campaign and overshadowed local campaigning, "there was a perception that they were useful and an expectation that they might become a permanent feature of the election process", said Johnston.

Debates have happened in each election since but no one format has ever been repeated. Dealignment in politics in the UK has seen more voters "willing to consider alternatives to the Conservatives, Labour, and even the Liberal Democrats", said political communication expert Nick Anstead in a blog for the LSE. It was "these dynamics which framed the 7-way debate format chosen in 2015", which featured all the parties standing in Great Britain.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Theresa May was the first prime minister since 2010 to refuse to take part in televised debates, with her home secretary Amber Rudd representing the Conservative Party in 2017. It was a decision that "went over poorly in the focus groups and was part of why [May's] election campaign went badly", said Stephen Bush in the Financial Times. May later expressed regret to Sky News over this decision: "I should have done the TV debates. I didn't because I had seen them suck the life blood out of David Cameron's campaign."

In 2019, Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn went head-to-head in the first TV debates to feature just the Labour and Conservative leaders. The first clash drew an average audience of 6.7 million – "a third of the British TV audience", said HuffPost.

Do they make a difference?

Research is scarce but surveys of voters have indicated that the leaders' debates "engaged voters that would not normally pay as much attention to the election campaign, in particular younger voters", said Johnston.

However, a recent study by Harvard Business School found that "presidential or prime ministerial TV debates, campaigns' most salient events, do not play any significant role in shaping voters' choice of candidate".

The televised debates are essentially "private events conducted by political parties, who do deals with individual broadcasters", said Sky News's Adam Boulton. This means the TV channels "compete to be first and splashiest" while the parties "work to minimise risk by making the debates as unlikely to change opinions as possible".

Canada, "a comparable Westminster-style parliamentary democracy", said Anstead, "offers one possibility" to fix the system. In the run-up to the 2019 election, the country established an independent debate commission and while it is too late to instigate such a system for this year's general election, "we can at least hope it is the last British election where debate organisation occurs in such a haphazard manner".

What might this year's format be?

The Lib Dems, Greens and SNP "face being cut out of televised leadership debates, as broadcasters plan to focus on two head-to-head contests between Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer", said The Guardian's political media editor Jim Waterson.

So far the format for this election hasn't been decided but televised debates "are a moment in this campaign when things could change, and therefore if Starmer could find a way to avoid doing them, he should take it", said Bush in the FT.

But if the Labour leader doesn't want to attract the negative attention received by May, the 2019-style "two head-to-head debates with Rishi Sunak, and a third appearance in front of a Question Time-style audience" would be best. That allows him to avoid a proper debate with those parties to the left of Labour who would attack him "over his policy programme and the Israel-Hamas war in particular", said Bush.

Jamie Timson is the UK news editor, curating The Week UK's daily morning newsletter and setting the agenda for the day's news output. He was first a member of the team from 2015 to 2019, progressing from intern to senior staff writer, and then rejoined in September 2022. As a founding panellist on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast, he has discussed politics, foreign affairs and conspiracy theories, sometimes separately, sometimes all at once. In between working at The Week, Jamie was a senior press officer at the Department for Transport, with a penchant for crisis communications, working on Brexit, the response to Covid-19 and HS2, among others.

-

Seahawks trounce Patriots in Super Bowl LX

Seahawks trounce Patriots in Super Bowl LXSpeed Read The Seattle Seahawks won their second Super Bowl against the New England Patriots

-

Political cartoons for February 9

Political cartoons for February 9Cartoons Monday's political cartoons include 100% of the 1%, vanishing jobs, and Trump in the Twilight Zone

-

Who is Starmer without McSweeney?

Who is Starmer without McSweeney?Today’s Big Question Now he has lost his ‘punch bag’ for Labour’s recent failings, the prime minister is in ‘full-blown survival mode’

-

Who is Keir Starmer without Morgan McSweeney?

Who is Keir Starmer without Morgan McSweeney?Today’s Big Question Now he has lost his ‘punch bag’ for Labour’s recent failings, the prime minister is in ‘full-blown survival mode’

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to Starmer

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to StarmerThe Explainer Texts and emails about Mandelson’s appointment as US ambassador could fuel biggest political scandal ‘for a generation’

-

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?Today's Big Question Could political pressure overcome legal obstacles and force either man to give evidence over their relationship with Jeffrey Epstein?

-

Reforming the House of Lords

Reforming the House of LordsThe Explainer Keir Starmer’s government regards reform of the House of Lords as ‘long overdue and essential’

-

How long can Keir Starmer last as Labour leader?

How long can Keir Starmer last as Labour leader?Today's Big Question Pathway to a coup ‘still unclear’ even as potential challengers begin manoeuvring into position

-

What is at stake for Starmer in China?

What is at stake for Starmer in China?Today’s Big Question The British PM will have to ‘play it tough’ to achieve ‘substantive’ outcomes, while China looks to draw Britain away from US influence

-

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?Today's Big Question PM condemns US tariff threat but is less confrontational than some European allies