Should news outlets publish gruesome photos of gun violence victims?

The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The recent gun massacres in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo, New York, have once again raised an old question: Should journalists publish pictures of the grisly aftermath of gun violence, so that Americans can't duck the consequences of our permissive gun laws? Or do such images invade the privacy of grieving families and harm them even further?

"A debate has started that, perhaps, images from these horrific events be shared with the public — just to show how truly gruesome it is," Tom Jones writes for Poynter. CNN's Jake Tapper has weighed in on that debate, suggesting Americans need a "shock to the system" that "would prompt our leaders to figure out how to make sure society can stop these troubled men — and it's almost always men — from obtaining these weapons used to slaughter our children."

What would be the benefits of publishing such pictures? And can it be done in a way that doesn't create more harm?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Something must be done to shake up the gun control debate

"It's time — with the permission of a surviving parent — to show what a slaughtered 7-year-old looks like," Temple University journalism dean David Boardman tweeted following the Uvalde attack. He expanded on the proposal in an interview with Philadelphia Magazine. "For most mainstream publications, particularly when it comes to dead bodies of any age, there is a big red flag," Boardman said, but "there are occasions where the use of such photographs is deemed to be of enough value that it's worth whatever offense you might cause." Gun massacres are happening on a regular basis ten years after Sandy Hook, "so I think we, as journalists, have to face up to the fact that our textual description of this sort of heinous crime … isn't moving citizenry and isn't moving, certainly, the political machine the way it needs to be moved." That's why it's time "to graphically show the public and, by extension, the members of the United States Senate, what this sort of devastation looks like." Such a decision should probably be a one-off. "I'm quite sure that I would not want it [to] be the standard moving forward."

That's what journalism is supposed to do

"I don't think people understand what bullets, especially bullets fired from high-powered rifles, do to children's bodies. They destroy their bodies is what they do," The Washington Post's John Woodrow Cox said on CNN's Reliable Sources. If lawmakers are going to continue to back permissive gun laws, "then they should know the cost. They should know the price that children pay in graphic form." It's hard to know how best to present such information without inflicting further harm on families and other survivors, "but what I find most often is that these kids are desperate to share their stories, they're desperate to be heard because oftentimes, the survivors are overlooked, you know. All of our headlines are about who died." One big problem: Even as the mass shooting epidemic has persisted for years, "we have never grasped in this country the scope of this crisis, not just school shootings, but gun violence in general. This is a thing that affects not hundreds or thousands of children but literally millions of children every year." So it's worth doing what it takes to make the public grasp the nature of the crisis, even if it means changing the minds of only a few people. "If it can convince a gun owner to lock up his gun, then, you know, maybe one life has changed, maybe one life has [been] saved."

There might be unintended consequences

"Photographs tend to start arguments, not end them," journalism professor Susie Linfield writes in The New York Times. While there are examples of dramatic pictures changing the course of a political debate — think of Emmett Till's effect on the civil rights struggle, or the photo of a napalm-scorched girl during the Vietnam War — shocking photos are often ignored, or can lead to unexpected outcomes. "Photographs of skeletal Somalis dying of hunger — those by James Nachtwey are particularly brutal — were one of the key inspirations for the U.S.-United Nations intervention in Somalia in late 1992; less than one year later, Paul Watson's horrific photograph of a gleeful crowd dragging an American soldier's naked corpse contributed to our hasty retreat." Perhaps the best solution is to require our political leaders to look at the photos, but not to keep our expectations low. "People, not photographs, create political change, which is slow, difficult and unpredictable. Don't ask images to think, or to act, for you."

The effect would probably be short-lived

"Research has shown that when audiences feel emotionally connected with news events, they're more likely to change their views or take action," the University of Oregon's Nicole Smith Dahmen wrote for Photo District News after the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. "But the power of images is limited." While shocking images can provoke "short bursts of activism," that power dissipates quickly: "For example, in 2015, following the publication of the harrowing image of a drowned Syrian boy lying face down in the sand, donations to the Red Cross briefly spiked. But within a week, they returned to their typical levels."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The dead deserve their dignity

While it's important to help the public understand the cost of gun violence, Texas Tribune's Sewell Chan tells Vanity Fair, it's also hugely important to be sensitive to survivors. Perhaps the media should "do a little less of shoving a microphone in the face of someone who's just experienced unspeakable loss" and instead focus more on "policy, more about the NRA, more about politicians and their voting records," argues Chan. While it's understandable that some journalists advocate publishing gruesome and shocking photographs, there are concerns "that could come across as exploitative or unethical or unseemly … People have a right to dignity, even, or especially, in death."

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Political cartoons for February 20

Political cartoons for February 20Cartoons Friday’s political cartoons include just the ice, winter games, and more

-

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?The Explainer New drug could reverse effects of sepsis, rather than trying to treat infection with antibiotics

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Campus security is under scrutiny again after the Brown shooting

Campus security is under scrutiny again after the Brown shootingTalking Points Questions surround a federal law called the Clery Act

-

Sole suspect in Brown, MIT shootings found dead

Sole suspect in Brown, MIT shootings found deadSpeed Read The mass shooting suspect, a former Brown grad student, died of self-inflicted gunshot wounds

-

2 kids killed in shooting at Catholic school mass

2 kids killed in shooting at Catholic school massSpeed Read 17 others were wounded during a morning mass at the Annunciation Catholic School in Minneapolis

-

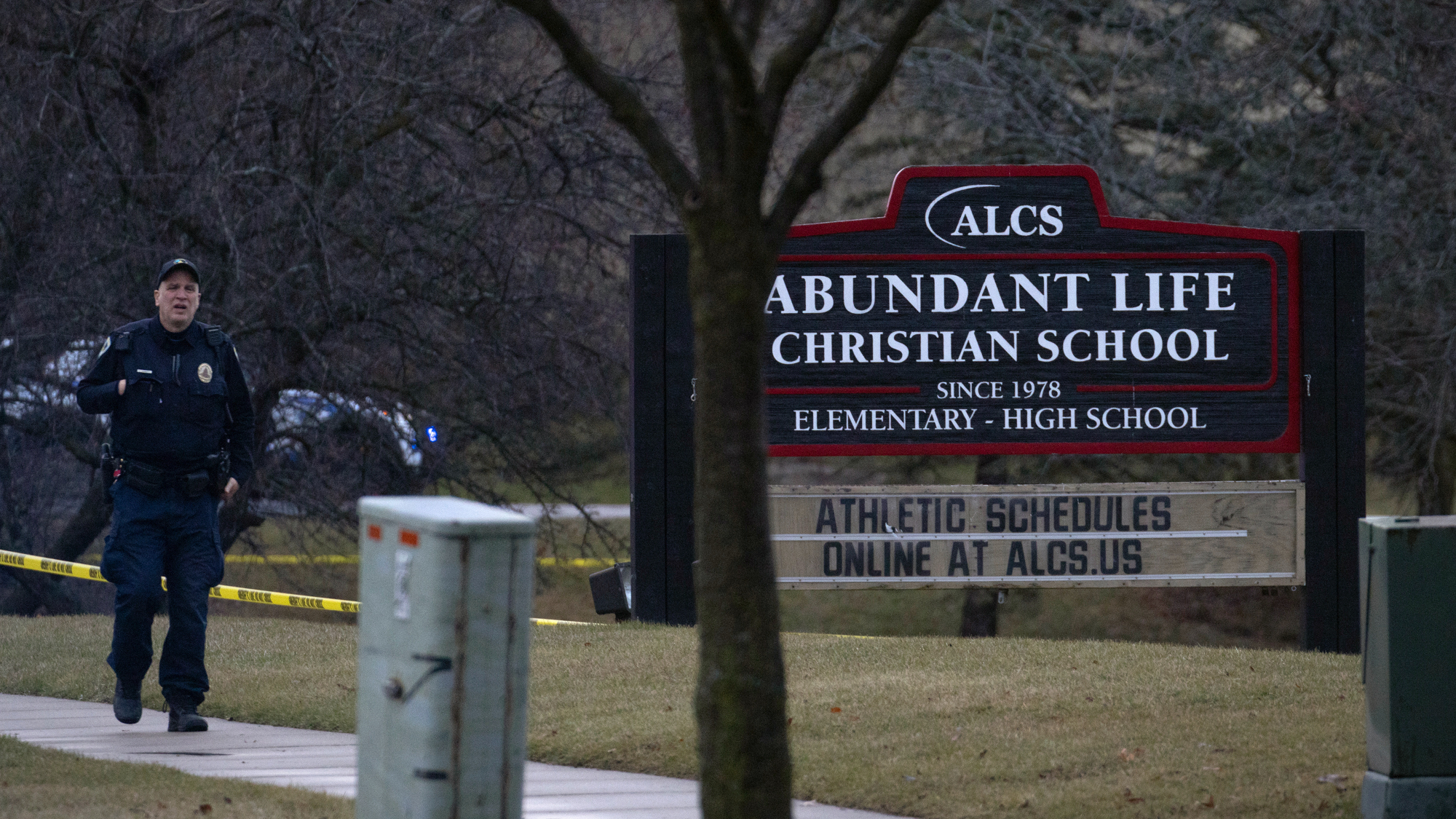

Teenage girl kills 2 in Wisconsin school shooting

Teenage girl kills 2 in Wisconsin school shootingSpeed Read 15-year-old Natalie Rupnow fatally shot a teacher and student at Abundant Life Christian School

-

Father of alleged Georgia school shooter arrested

Father of alleged Georgia school shooter arrestedSpeed Read The 14-year-old's father was arrested in connection with the deaths of two teachers and two students

-

Teen kills 4 in Georgia high school shooting

Teen kills 4 in Georgia high school shootingSpeed Read A student shot and killed two classmates and two teachers at Apalachee High School

-

Parents of school shooter sentenced to 10-15 years

Parents of school shooter sentenced to 10-15 yearsSpeed Read Jennifer and James Crumbley are the first parents to be convicted in a US mass shooting

-

Michigan shooter's dad guilty of manslaughter

Michigan shooter's dad guilty of manslaughterspeed read James Crumbley failed to prevent his son from killing four students at Oxford High School in 2021