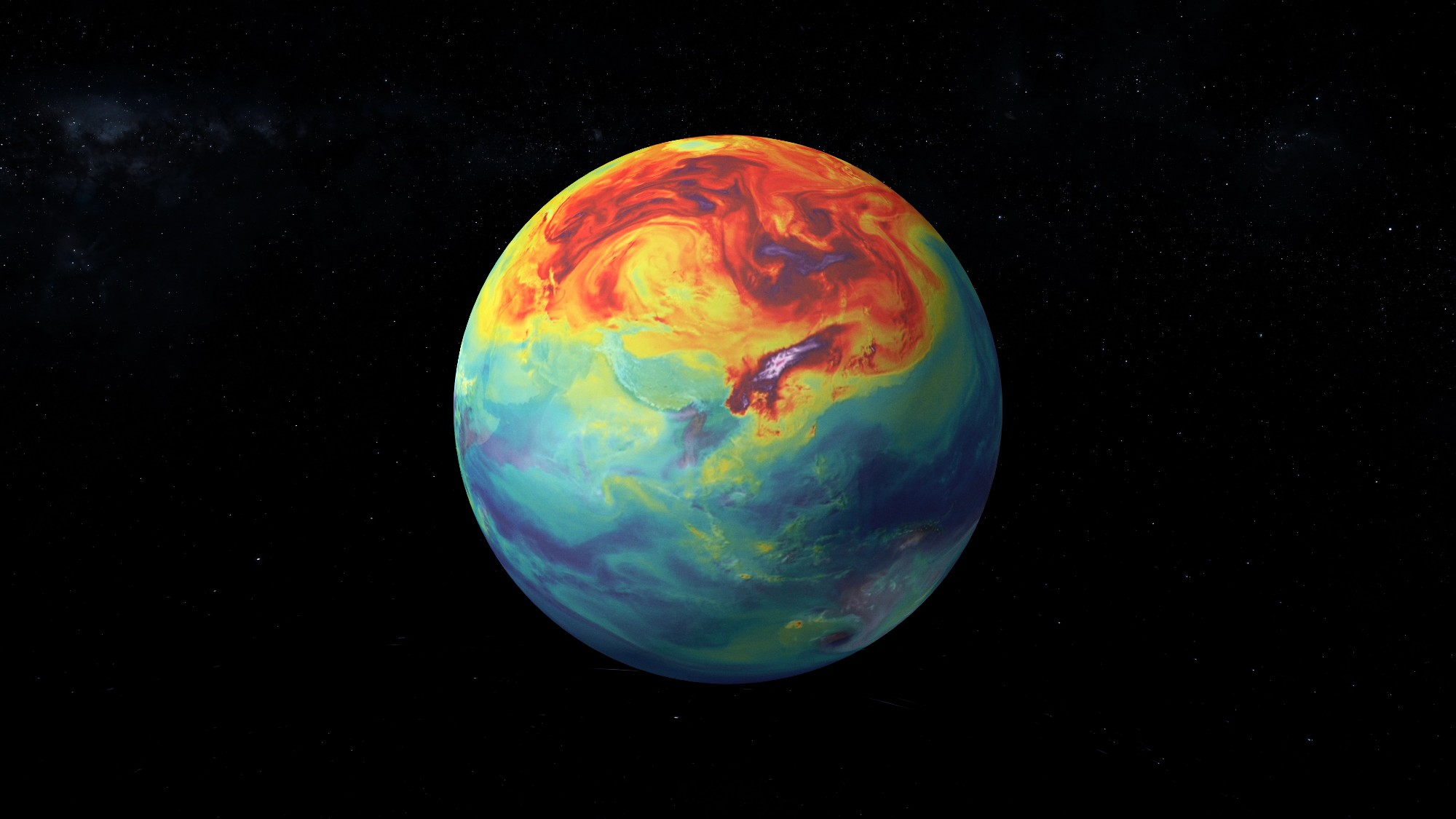

Is China going to fry the global climate?

Soon, China will be responsible for more total carbon dioxide emissions than any other country

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The last month has seen a nearly continuous series of climate disasters striking across the world: extreme heat in the Pacific Northwest, wildfires in the western U.S. and Canada blanketing half the continent with smoke, extreme flooding in Germany, India, and China, and on and on. We surely haven't seen the last climate disaster of 2021.

Climate change is a global problem, and all countries are implicated. But one country is far more important to the world's climate future than any other: China. The decisions made by the Chinese leadership will largely determine whether the climate fries.

When speaking about China's emissions, one sometimes hears the argument that rich countries should bear the brunt of the effort against climate change, because the U.S. and Europe are responsible for the bulk of historical emissions.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This argument is pretty strained to begin with. If climate change is a potentially existential threat to human society (and it is), surely stopping it takes priority over anything else, including litigating who should be most responsible for mitigating it. I do agree that rich countries should be morally obliged to contribute more than poorer ones because of their greater historical emissions, but at the end of the day, simply wrenching down emissions must matter more than that. By the same token, allowing poorer countries to burn carbon is not going to do them much good if that brings about climate change that will destroy their economies anyway. In a critical emergency, everybody has to do as much as they can, as fast as they can.

And besides, a significant portion of developed-world emissions happened before the point when climate science was established and brought before policymakers in a sustained way, in about the 1960s and 1970s. If high-emitting poorer countries deserve some latitude because rich ones got to burn carbon freely in the past, then they also deserve less for being fully aware of climate change now.

Second, China is not that poor anymore. Its currency-adjusted, per-person GDP is about $18,900, according to the IMF — in the same league as Thailand or Mexico, or twice as rich as Namibia, or three times as rich as Belize. China's economy is now the largest in the world, and it will only become stronger in the near future. Unlike Burundi, China can afford to do its part.

But most importantly, the sheer scale of China's emissions dwarfs all other factors. It now emits more greenhouse gases than the U.S. and the EU combined — indeed, a recent report from the Rhodium Group found that in 2019, China emitted more than all developed countries put together. It is true that rich countries are partly responsible for Chinese emissions because they buy so many exports from that country, but the effect is relatively modest. Adjusting for trade effects only increases American emissions by about 6.3 percent, and decreases those of China by about 10 percent.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This means that (absent massive changes in emissions) quite soon China will be responsible for more total emissions than any other country. Hannah Ritchie has collected data on cumulative emissions from fossil fuels and cement production for Our World in Data, which gives an upper bound on how long this will take. Up to 2019, the U.S. was responsible for about 410 billion metric tons of total carbon dioxide production, while China was responsible for 220 billion metric tons — already a very considerable quantity. If we simply assume the 2019 figures of annual carbon dioxide production totals (again from fossil fuels and cement) of 5.28 billion tons and 10.17 billion tons respectively remain as they are indefinitely, then China's total will surpass that of America in 2058 — just 37 years from now.

And that date is certainly an overestimate, even without any serious climate policy. This measurement does not include other greenhouse gases like methane, or carbon dioxide production from land use changes, both of which are significant in China. It also does not account for the fact that U.S. emissions have declined by about 15 percent since 2007, while China's have continued to increase.

Now, China has recently unveiled an emissions-trading scheme that is meant to provide an incentive to cut greenhouse gas production. It's a positive step, but as the European experience demonstrates, will probably take many years to have much of an effect. Meanwhile, coal-dependent sectors are extremely powerful in China, and the country is continuing to double down on coal power. It brought 38.4 gigawatts of new coal power online in 2020 alone, which is more than three times what the entire rest of the world put together that year. It also has 247 gigawatts of additional coal power in planning and development — more capacity than the entire extant American coal fleet (which is rapidly going out of business, incidentally).

It would be unwise to simply trust China to do the right thing. So what might the rest of the international community do?

Military force can be dismissed out of hand. China is a nuclear-armed power and nuclear war cannot be risked. America does have a gigantic military, but it has not faced a truly formidable opponent since the Second World War, and has spent the last 50 years losing repeatedly to ill-equipped guerrilla bands. Pentagon weapons procurement is profoundly corrupt; American forces are heavily based around ultra-expensive ships and planes that would be useless sitting ducks in a real fight. In recent wargames attempting to model a conflict with China, the American side was defeated easily.

Diplomacy and trade are more promising avenues. As Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis write in their book Trade Wars Are Class Wars, the Chinese economy is heavily based on exports in part because it is hideously unequal, and therefore its workers do not have the income to buy what they produce. China depends on the U.S. serving as the consumer of last resort — swallowing gigantic trade deficits year after year. Taking advantage of this fact to rejigger the trade system to push China to decarbonize is not a bad strategy.

Unfortunately, for such a move to have diplomatic credibility, America would have to do its part on climate change in a serious way, not just aimlessly drift in sort of the right direction because solar panels and wind turbines are getting cheap. I see little chance of that happening. Not only is President Biden's infrastructure bill — the only piece of climate legislation that is likely to pass for the next decade — far, far short of what is needed (and may not even pass at all), American institutions are simply not suited to accomplishing anything, ever. As historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote in his autobiography: "Forced into the straitjacket of an 18th-century constitution reinforced by two centuries of talmudic exegesis by the lawyers, the theologians of the republic, the institutions of the USA are far more frozen into immobility than those of almost all other states."

So trust it is. The only serious hope I see on the horizon is that the Chinese leadership itself will recognize the terrific danger climate change poses to China itself. Continuing to burn coal is going to hurt China more than Europe or the U.S. — it already faces extreme air quality problems, desertification, loss of water supplies, flooding, heat waves, and so forth. All that will get worse and worse the more carbon it burns. President Xi: The fate of Chinese society is in your hands.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish lithium

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish lithiumUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

How climate change is affecting Christmas

How climate change is affecting ChristmasThe Explainer There may be a slim chance of future white Christmases

-

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusion

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusionThe Explainer Harnessing the reaction that powers the stars could offer a potentially unlimited source of carbon-free energy, and the race is hotting up

-

Africa could become the next frontier for space programs

Africa could become the next frontier for space programsThe Explainer China and the US are both working on space applications for Africa

-

Canyons under the Antarctic have deep impacts

Canyons under the Antarctic have deep impactsUnder the radar Submarine canyons could be affecting the climate more than previously thought

-

NASA is moving away from tracking climate change

NASA is moving away from tracking climate changeThe Explainer Climate missions could be going dark

-

What would happen to Earth if humans went extinct?

What would happen to Earth if humans went extinct?The Explainer Human extinction could potentially give rise to new species and climates

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution