Eclipses 'on demand' mark a new era in solar physics

The European Space Agency's Proba-3 mission gives scientists the ability to study one of the solar system's most compelling phenomena

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

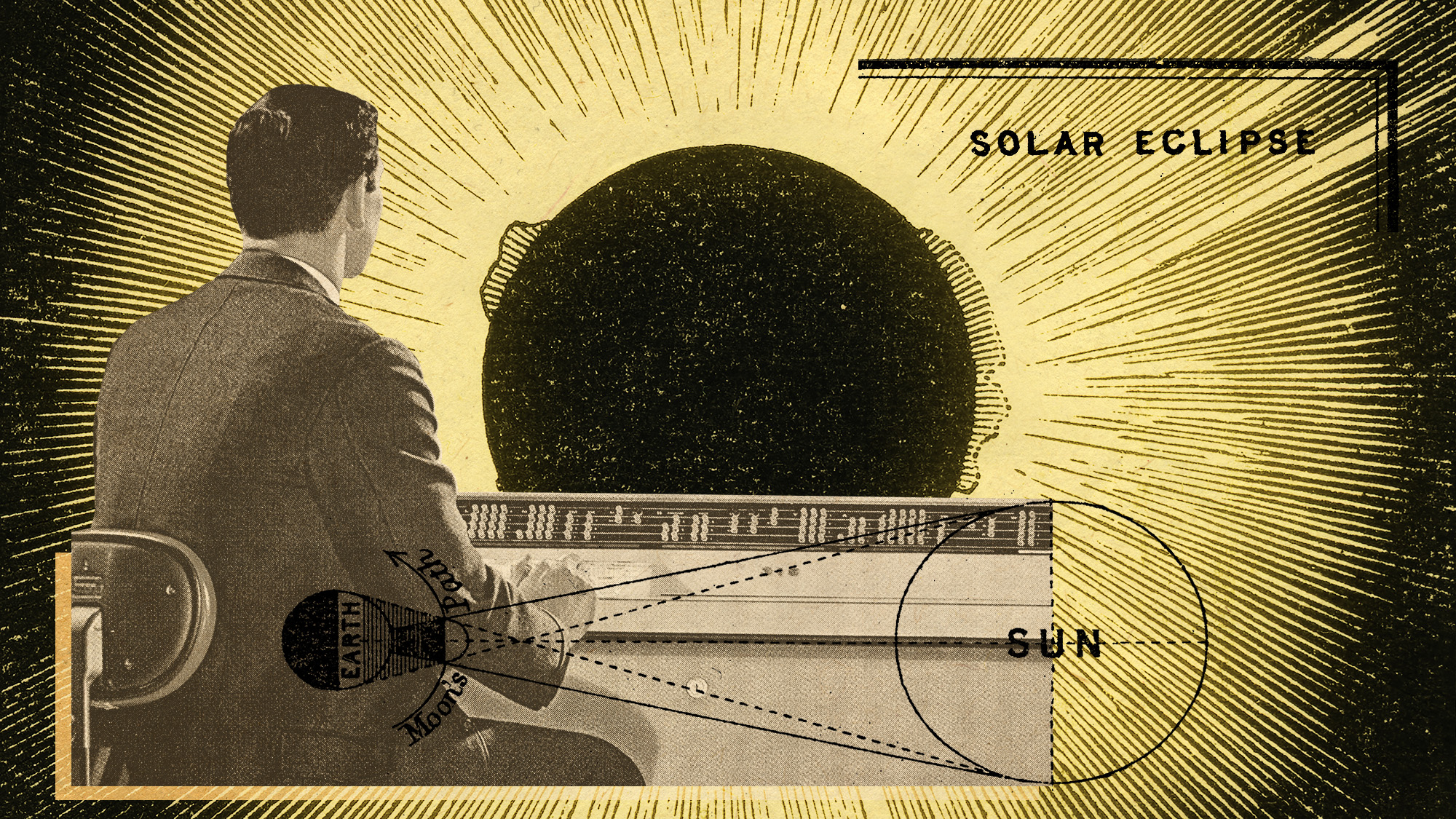

Human beings have long lived in awe of the vast and starry skies — particularly during a solar eclipse, wherein the very laws of nature feel inverted. Before modern astronomy, solar eclipses were often assigned mythological or theological significance, which likely contributed to our enduring fascination with them.

That fascination took a seismic step forward this month, with the European Space Agency's launch of its Proba-3 mission. The groundbreaking project will enable researchers to create artificial solar eclipses for study on demand. Comprised of twin satellites Occulter and Coronagraph, Proba-3 will see the pair working in tandem to create a "precisely-controlled shadow from one platform to the other," the ESA said, opening "sustained views of the sun's faint surrounding corona."

Here's what makes the Proba-3 mission so unique, and what researchers hope to get out of it now that the project is off the ground.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

'Accuracy down to the thickness of the average fingernail'

The Proba-3's twin satellites, both of which were launched together from India's Satish Dhawan Space Center earlier this month, are each "about the size of a washing machine," The Washington Post said. Once in position, Occulter will "line itself up with the sun and use a disc — the stand-in for the moon — to cast a shadow onto the Cornograph," which can then be analyzed and studied like a natural eclipse. That may seem like a fairly straightforward proposition, but what makes the Proba-3 mission so special is the astonishing degree of precision involved: To be considered successful, the mission's satellites must "achieve positioning accuracy down to the thickness of the average fingernail while positioned one and a half football pitches apart," said Proba-3 mission manager Damien Galano. And all of this while speeding around the Earth.

If everything goes to plan, the receiving Coronagraph satellite will then be able to record data on the sun's corona, its "wispy, unfathomably hot outer atmosphere, which is usually lost in our star's glare," Space.com said. (The Week and Space.com are both owned by Future plc.) Once operational, the satellites will circle the Earth every 19 hours on a "lopsided" elliptical orbit, The Associated Press said. Twice a week, six of those hours "at the farther end of certain orbits" will be spent creating and studying artificial eclipses, while other loops will be focused on "formation flying experiments."

Solar mysteries and formation flying futures

Scientists hope that by artificially generating eclipses, they can study the "counterintuitive" temperature of the sun's corona, which is approximately 200 times hotter than the star's actual surface, Gizmodo said. The corona also "drives solar wind and coronal mass ejections," which can affect certain technologies both in orbit around, and on, Earth. But ultimately, it is Proba-3's extraordinary precision in orbit that "may end up being the mission's most lasting legacy," Space.com said.

Lessons from the project could someday "be extended to larger pairs of satellites," which would then be able to "block out starlight and allow scientists to go planet hunting," the Post said. "Imagine multiple small platforms working together as one to form far-seeing virtual telescopes or arrays," said the ESA. Proba-3 scientists expect the project will begin pushing out its eclipse observations "in about four months."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Rafi Schwartz has worked as a politics writer at The Week since 2022, where he covers elections, Congress and the White House. He was previously a contributing writer with Mic focusing largely on politics, a senior writer with Splinter News, a staff writer for Fusion's news lab, and the managing editor of Heeb Magazine, a Jewish life and culture publication. Rafi's work has appeared in Rolling Stone, GOOD and The Forward, among others.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concerns

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concernsThe Explainer The agency hopes to launch a new mission to the moon in the coming months

-

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

Cows can use tools, scientists report

Cows can use tools, scientists reportSpeed Read The discovery builds on Jane Goodall’s research from the 1960s

-

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwise

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwiseUnder the radar We won’t feel it in our lifetime