Bobby Charlton: England's old-fashioned sporting hero

Not only was Sir Bobby one of the country's greatest-ever footballers he was lauded for his demeanour on and off the pitch

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Bobby Charlton, who has died aged 86, was one of the finest footballers England has ever produced, said The Guardian – and undoubtedly the most successful.

A member of the team that won England the World Cup in 1966, he also won, with his beloved Manchester United, the FA Cup, the Football League and the European Cup. Known for his grace and balance, “raking passes and explosive long-range shots, with either foot”, he scored 49 goals for England in 106 appearances, and 249 in 758 games for United – a record only surpassed by Wayne Rooney in 2017.

He embodied a golden age of English football, but was also involved in one of the game’s “darkest moments”, the 1958 Munich air disaster. Charlton became one of the most famous footballers in the world; the only two words of English many people knew were “Bobby Charlton”. Yet he was not only revered for his talent on the pitch. When London was swinging, Charlton, with his gentlemanly demeanour and wispy comb-over, was an old-fashioned sporting hero.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

'England's greatest-ever footballer'

More recently, he had become a living bridge to what we think of as a more noble time, said Martin Samuel in The Times. He played in an era when footballers travelled on public transport, not in Lamborghinis, and “lived on well appointed yet recognisable streets, not in gated mansions”. His ambition during his years at United, his wife Norma once said, was simply to save up enough money so that he could start a small business when he retired. One can only imagine what this “unassuming” man would have made of the tributes that have poured in this week.

“At the height of his playing career, a respected writer described Charlton as England’s greatest-ever footballer. Far from revelling in the praise, Charlton had the good grace to appear embarrassed. ‘Well,’ he shrugged, finally, ‘he’s entitled to his opinion.’”

Bobby Charlton was born in the mining village of Ashington, in Northumberland. His father Robert was a miner with little interest in football, but his mother Cissie’s four brothers were all professional players, and their cousin was the Newcastle legend Jackie Milburn. Passionate about football, she encouraged both Bobby and his older brother Jack to play. Jack was the less gifted of the two (and a very different character, on the pitch and off) but they would both end up on the 1966 World Cup winning side.

Aged nine, Bobby was small and thin, said Ivan Ponting in The Independent, yet “he could dominate a game in which the other boys were five years his senior. Indeed, the sublime body swerve was already in joyful evidence as he weaved past opponents in epic contests” in Ashington’s terraced streets. A reserved, studious child (in contrast to the outspoken, rebellious Jack), he passed the 11-plus, but declined to go to his local grammar school because their game was rugby.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

'You're in paradise now'

By his mid-teens, the clubs were vying to get hold of him; he opted for Manchester United, where Matt Busby was establishing a reputation for nurturing young talent, said The Times. Arriving aged 16, he was assigned to a junior side playing local factory teams. It was a gruelling apprenticeship, he said, but a valuable one. He also valued the advice he received from his mentor, Jimmy Murphy: “You see all those people going past the ground on their way to work? Well, you have to make sure that when they come to watch a football match, you don’t bore them.”

Charlton joined United full time in 1956, and made his debut a few days before his 19th birthday. As he took to the pitch at Old Trafford, he remembered saying to himself: “Bobby lad, there are no two ways about it. You’re in paradise now.” Although he was doing National Service at the time, he played 17 games that season, in which United – made up of the young players who became known as the “Busby Babes” – won the league title. The next year, they became the first English team to compete in the European Cup.

En route home from a quarter-final victory in Belgrade, their plane crashed during take- off from an icy Munich Airport, where it had stopped to refuel. Twenty-three people were killed, including eight of his team members, several of whom were his close friends. Two other players were never able to play again. Busby was so badly injured, he was given the last rites. Charlton was hurled from the plane and escaped with a graze. He described it as a miracle, but he was plagued by survivor’s guilt, and became more taciturn, more withdrawn. His brother said that he was never the same again. Jack expressed pride in “our kid” in public, but the brothers were often estranged. Seemingly, their feud stemmed from their mother’s refusal to welcome Norma into the family. They were both strong women, Bobby said, but his loyalty was always to his wife, who survives him, with their daughters.

Remarkably, he was back on the pitch within weeks of the crash, and that year he helped his traumatised and depleted team to reach the FA Cup final, which they lost to Bolton Wanderers. But it wasn’t until the mid-1960s, when he was switched from the wing to a deep-lying centre-forward position, that he came into his own, aided by the arrival of Denis Law and George Best.

'The glorious trinity'

They formed a “glorious trinity”, said Ivan Ponting, which took United to the peaks. It won the FA Cup in 1963, the League in 1965 and 1967, and in 1968, fulfilled Busby’s dream by beating Benfica to become the first English team to win the European Cup. Overcome by the significance of this victory, and memories of his lost teammates, Charlton wept uncontrollably – and was left so exhausted by his efforts on the pitch, he could scarcely lift the trophy, and later fainted in his room.

By then he had of course also helped England win the World Cup, by scoring crucial goals against Mexico and Portugal, and by relentlessly marking West Germany’s star player Franz Beckenbauer, who’d been ordered to do the same to him, in the final. He made his 106th and final appearance for England in the 1970 World Cup in Mexico, where they were eliminated by West Germany in the quarter-finals.

By around that time, his game was starting to decline. Frustrated by events at Manchester United, where Denis Law was rarely fully fit and George Best was squandering his talents, he decided to retire. He played his last game in 1973, aged 35. In his 20-year career, he had picked up two bookings, and never been sent off. After an unsuccessful stint as manager of Preston North End, he set up a network of football schools, and became an ambassador for English football and for United, where he played a key role in recruiting Alex Ferguson. He retired from public life in 2020. His death leaves Geoff Hurst as the sole surviving member of England’s 1966 World Cup-winning team.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Indiana beats Miami for college football title

Indiana beats Miami for college football titleSpeed Read The victory completed Indiana’s unbeaten season

-

Who is to blame for Maccabi Tel Aviv fan-ban blunder?

Who is to blame for Maccabi Tel Aviv fan-ban blunder?Today’s Big Question MPs call for resignation of West Midlands Police chief constable over ‘dodgy’ justification of ban from Aston Villa match, but role of Birmingham Safety Advisory Group also under scrutiny

-

Amorim follows Maresca out of Premier League after ‘awful’ season

Amorim follows Maresca out of Premier League after ‘awful’ seasonIn the Spotlight Manchester United head coach sacked after dismal results and outburst against leadership, echoing comments by Chelsea boss when he quit last week

-

Coaches’ salary buyouts are generating questions for colleges

Coaches’ salary buyouts are generating questions for collegesUnder the Radar ‘The math doesn’t seem to math,’ one expert said

-

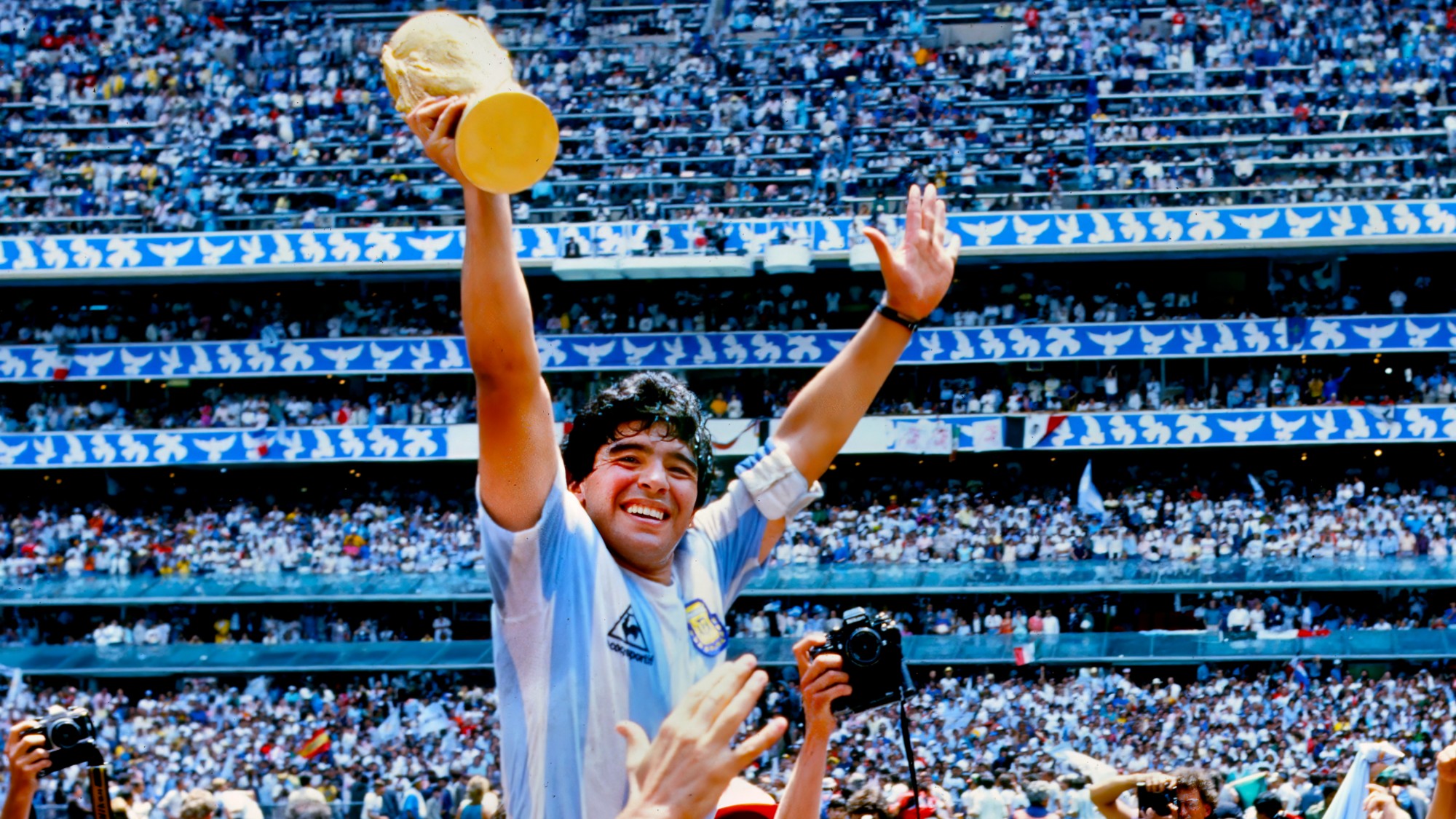

Five years after his death, Diego Maradona’s family demand justice

Five years after his death, Diego Maradona’s family demand justiceIn the Spotlight Argentine football legend’s medical team accused of negligent homicide and will stand trial – again – next year

-

Libya's 'curious' football cup, played in Italy to empty stadiums

Libya's 'curious' football cup, played in Italy to empty stadiumsUnder The Radar 'Curious collaboration' saw Al-Ahli Tripoli crowned league champions in Milan before a handful of spectators

-

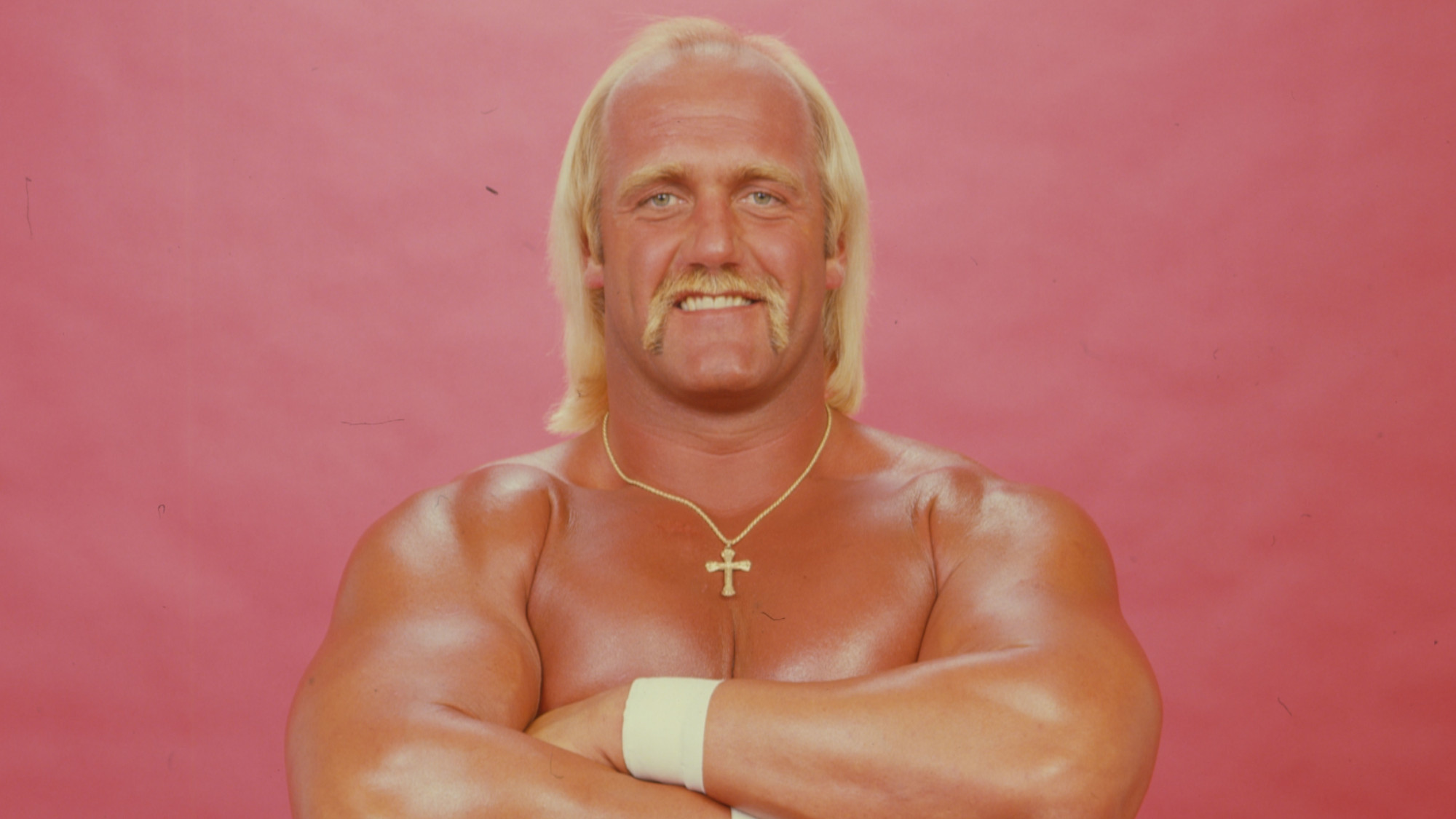

Hulk Hogan

Hulk HoganFeature The pro wrestler who turned heel in art and life