Is Putin toast?

Could the Wagner mutiny be the beginning of the end for Putin?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Russian President Vladimir Putin called for unity this week after a 24-hour mutiny by Wagner Group mercenaries, led by Yevgeny Prigozhin, who had marched toward Moscow. Putin called the organizers of the rebellion "traitors" and said they "would have been suppressed anyway," but argued he gave them time to come to their senses and turn around without bloodshed. Putin met with Russia's top security chiefs — including Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, whom Prigozhin wanted Putin to fire — as he tried to project stability.

Russians linked to the Kremlin expressed relief the uprising didn't spiral into civil war, but agreed the armed mutiny by fighters who had been a key part of Russia's war effort in Ukraine posed the most serious threat yet to Putin's 23-year hold on power. "It's a huge humiliation for Putin, of course. That's obvious," a Russian oligarch who knows Putin told the Financial Times. "Thousands of people without any resistance are going from Rostov almost to Moscow, and nobody can do anything. Then [Putin] announced they would be punished, and they were not. That's definitely a sign of weakness."

Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said the uprising showed that Russia is "an unpredictable state." U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the spectacle of Putin's government having to defend Moscow "against mercenaries of Putin's own making" — Wagner forces have been a key part of Russia's Ukraine invasion — exposed "cracks" in Putin's armor. Could this be the beginning of the end for Putin?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This shook Putin's "aura of power"

The Wagner mutiny "revealed the hidden instability of Putin's regime," said Max Boot in The Washington Post, and shook "his aura of power." And if the "infighting" in Russia distracts Putin and the Kremlin from the war in Ukraine, it could help Kyiv "score more battlefield successes," further undermining Putin's grip on power. "There is a lesson here for all future tyrants who might think of launching wars of aggression. Are you paying attention, Xi Jinping?"

This "fiasco" cost Putin his image as the person who "provides stability and guarantees security" to Russia's elite, Konstantin Remchukov, a Moscow newspaper editor with Kremlin connections, told Anton Troianovski of The New York Times. This could lead people close to Putin to try to persuade him not to run for re-election next spring, something they otherwise wouldn't have dared. "If I was sure a month ago that Putin would run unconditionally because it was his right," Remchukov said, "now I see that the elites can no longer feel unconditionally secure."

This might embolden Putin

This event is far from Putin's downfall, Nikolai Sokov, a senior fellow at the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Nonproliferation, said in Politico. "In fact, his support among the military might increase — both from Shoigu and top brass, but perhaps more importantly from generals and officers at the frontline." It might even have "helped somewhat defuse tensions that had been growing within the Russian body politic." Putin might "escalate hostilities" in Ukraine to "demonstrate, to Ukrainians and to the West, that he has not been weakened," said Serge Schmemann in The New York Times. A "few uniformed heads" might roll, but getting rid of some lousy generals won't hurt Russia's war effort. Putin also might use this as an excuse to launch an "even more vicious crackdown" on any Russian who questions him or his war.

It was telling that "nobody seemed to mind, particularly, that a brutal new warlord" was threatening Putin's regime, said Anne Applebaum in The Atlantic. Normally, "a certain kind of autocrat, of whom Putin is the outstanding example, seeks to convince people" not to pay attention to politics. Under Putin, the Kremlin has opened up "the famous 'firehose of falsehoods'" to make it impossible for people to know what's true. The idea is to make them see no point in protesting or engaging in politics at all. That has given Putin free reign. But "the side effect of apathy was on display" as citizens and the army stepped aside to let Wagner march toward the capital unchallenged. "For if no one cares about anything, that means they don't care about their supreme leader, his ideology, or his war."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Harold Maass is a contributing editor at The Week. He has been writing for The Week since the 2001 debut of the U.S. print edition and served as editor of TheWeek.com when it launched in 2008. Harold started his career as a newspaper reporter in South Florida and Haiti. He has previously worked for a variety of news outlets, including The Miami Herald, ABC News and Fox News, and for several years wrote a daily roundup of financial news for The Week and Yahoo Finance.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ comes into confounding focus

Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ comes into confounding focusIn the Spotlight What began as a plan to redevelop the Gaza Strip is quickly emerging as a new lever of global power for a president intent on upending the standing world order

-

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guarantee

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guaranteeTalking Points Zelenskyy says it is a requirement for peace. Will Putin go along?

-

Vance’s ‘next move will reveal whether the conservative movement can move past Trump’

Vance’s ‘next move will reveal whether the conservative movement can move past Trump’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What have Trump’s Mar-a-Lago summits achieved?

What have Trump’s Mar-a-Lago summits achieved?Today’s big question Zelenskyy and Netanyahu meet the president in his Palm Beach ‘Winter White House’

-

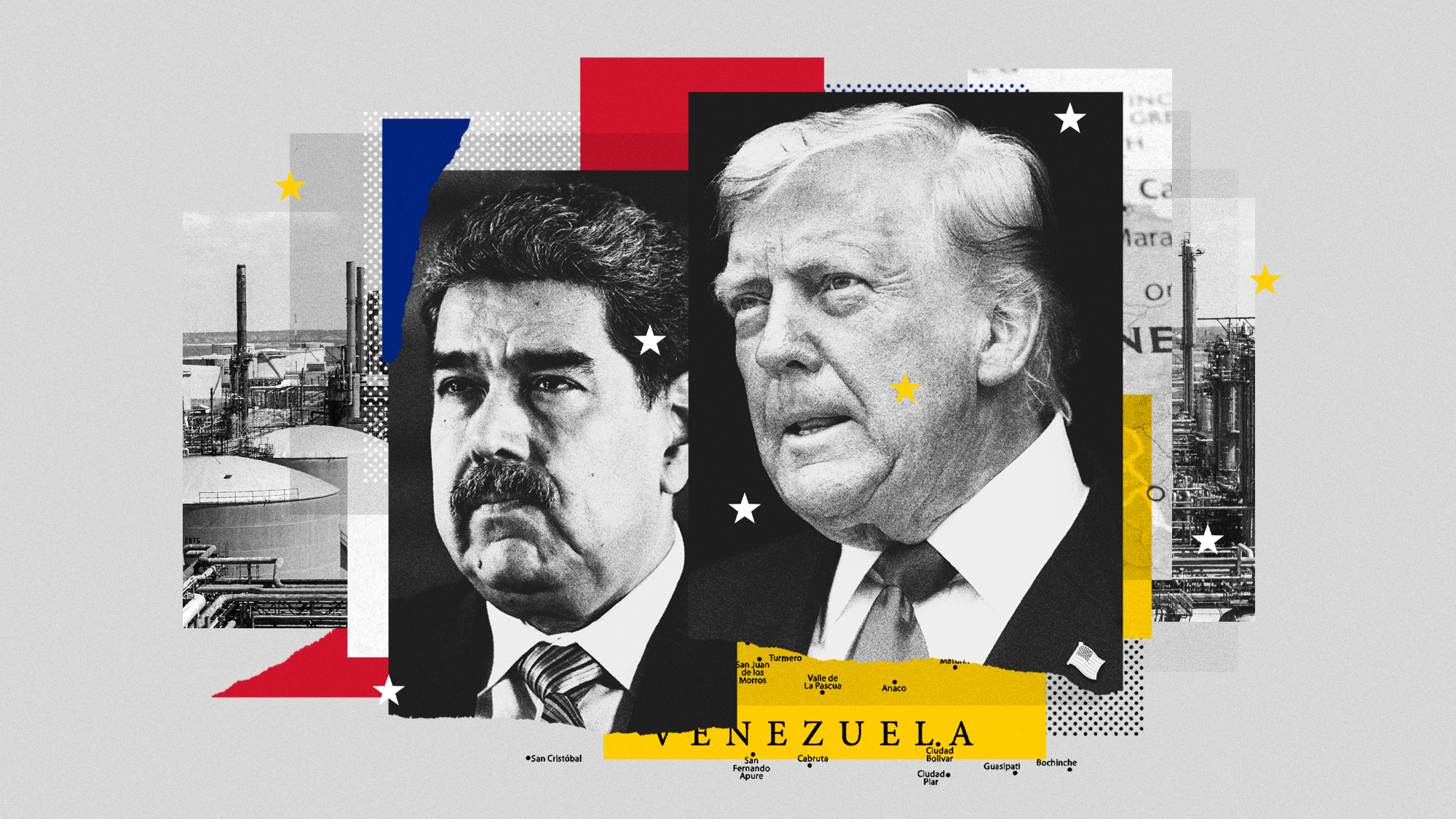

Why, really, is Trump going after Venezuela?

Why, really, is Trump going after Venezuela?Talking Points It might be oil, rare minerals or Putin

-

Who is paying for Europe’s €90bn Ukraine loan?

Who is paying for Europe’s €90bn Ukraine loan?Today’s Big Question Kyiv secures crucial funding but the EU ‘blinked’ at the chance to strike a bold blow against Russia

-

Will there be peace before Christmas in Ukraine?

Will there be peace before Christmas in Ukraine?Today's Big Question Discussions over the weekend could see a unified set of proposals from EU, UK and US to present to Moscow