Bank of England's Mark Carney in a proud Canuck tradition

'Rock star banker' isn't the first Canadian recruit to come to Britain's aid in difficult times

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

THE idea of Canada's 'rock star banker', Mark Carney, coming to the aid of the Bank of England in its hour of difficulty would seem uncontroversial, natural even, to the war generation on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Canadians were with us right from the start and in our darkest hour, declaring war against Germany just a week after we did. In September 1939, after the King had signed the official document at Windsor, the Canadian official historian wrote: "King George VI of England did not ask us to declare war for him – we asked King George VI of Canada to declare war for us."

The first Canadian troops arrived here a couple of months later. By the autumn of 1940 they had two infantry divisions in southern England, in a much better state of readiness than the bedraggled survivors of the British Expeditionary Force who had been forced to abandon most of their equipment at Dunkirk.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The familiar opening titles of Dad's Army unfolding to 'Who do you think you're kidding, Mister Hitler?' are slightly misleading. They show a defiant and aggressive arrow-shaped Union Jack somewhere on the Kent coast ready to take on the swastikas that have just unceremoniously ejected it from Europe. To reflect the true balance of forces available to counter a German invasion in the summer and autumn of 1940 the arrow should be half Union Jack and half Canadian Red Ensign (their flag until adopting the Maple Leaf in 1965).

If the Germans had managed to get ashore in any numbers they would have encountered British regular troops at their landing beaches, backed up by the likes of Captain Mainwaring and his men. But the formations which would have been sent into the battle once the main German landings had been identified would have been at least 50 per cent Canadian.

This was just the start of the Canadian contribution to the war. Realising in late 1941 that Hong Kong would be poorly defended against a Japanese invasion, and with British troops hard-pressed across the globe, Churchill asked the Canadians for reinforcements. The government in Ottawa immediately dispatched a brigade that fought bravely to the end, gaining 'the lasting honour' that Churchill had promised them and then enduring a barbaric captivity at the hands of the Japanese. The only Victoria Cross won in the Battle of Hong Kong was awarded (posthumously) to a sergeant-major in the Winnipeg Grenadiers.

In 1942, as British military planners began to think about an invasion of Europe, they decided, controversially, to mount an armed raid on a German-held port in France. They chose Dieppe. And they chose Canadian troops for the job.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Meanwhile, the Royal Canadian Navy was making a crucial contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic, sinking 31 U-boats and escorting countless vital convoys to the nearly-starving British Isles. By the end of the war the RCN was the third largest navy in the world.

Look at any major British military operation and the chances are it will have a strong Canadian flavour. On the night of 16 May, 1943, 19 Lancaster bombers took off from RAF Scampton for the Dambusters raid. Of 133 aircrew, 30 were Canadian, including Guy Gibson's navigator and front-gunner.

On D-Day a quarter of the troops that went ashore in the "British" sector were Canadian. They even had their own landing beach – Juno.

Mark Carney arrives in the UK as an individual reinforcement and will be attached to a British institution, just like the CANLOAN scheme under which 673 Canadian Army officers, almost all infantrymen, volunteered to serve with the British Army for the invasion of Europe in 1944. Usually, they were posted to the British regiment to which theirs was affiliated. Other than their 'Canada' shoulder-flash, they were completely integrated into the British Army. They were an extraordinary group of young men determined to be in the thick of the fighting as their casualty statistics testify: 128 were killed in action and 310 wounded in the 11 months between D-Day and the German surrender.

We have every reason to hope the GOVERNORLOAN scheme proves as impressive.

-

Touring the vineyards of southern Bolivia

Touring the vineyards of southern BoliviaThe Week Recommends Strongly reminiscent of Andalusia, these vineyards cut deep into the country’s southwest

-

American empire: a history of US imperial expansion

American empire: a history of US imperial expansionDonald Trump’s 21st century take on the Monroe Doctrine harks back to an earlier era of US interference in Latin America

-

Elon Musk’s starry mega-merger

Elon Musk’s starry mega-mergerTalking Point SpaceX founder is promising investors a rocket trip to the future – and a sprawling conglomerate to boot

-

The end for central bank independence?

The end for central bank independence?The Explainer Trump’s war on the US Federal Reserve comes at a moment of global weakening in central bank authority

-

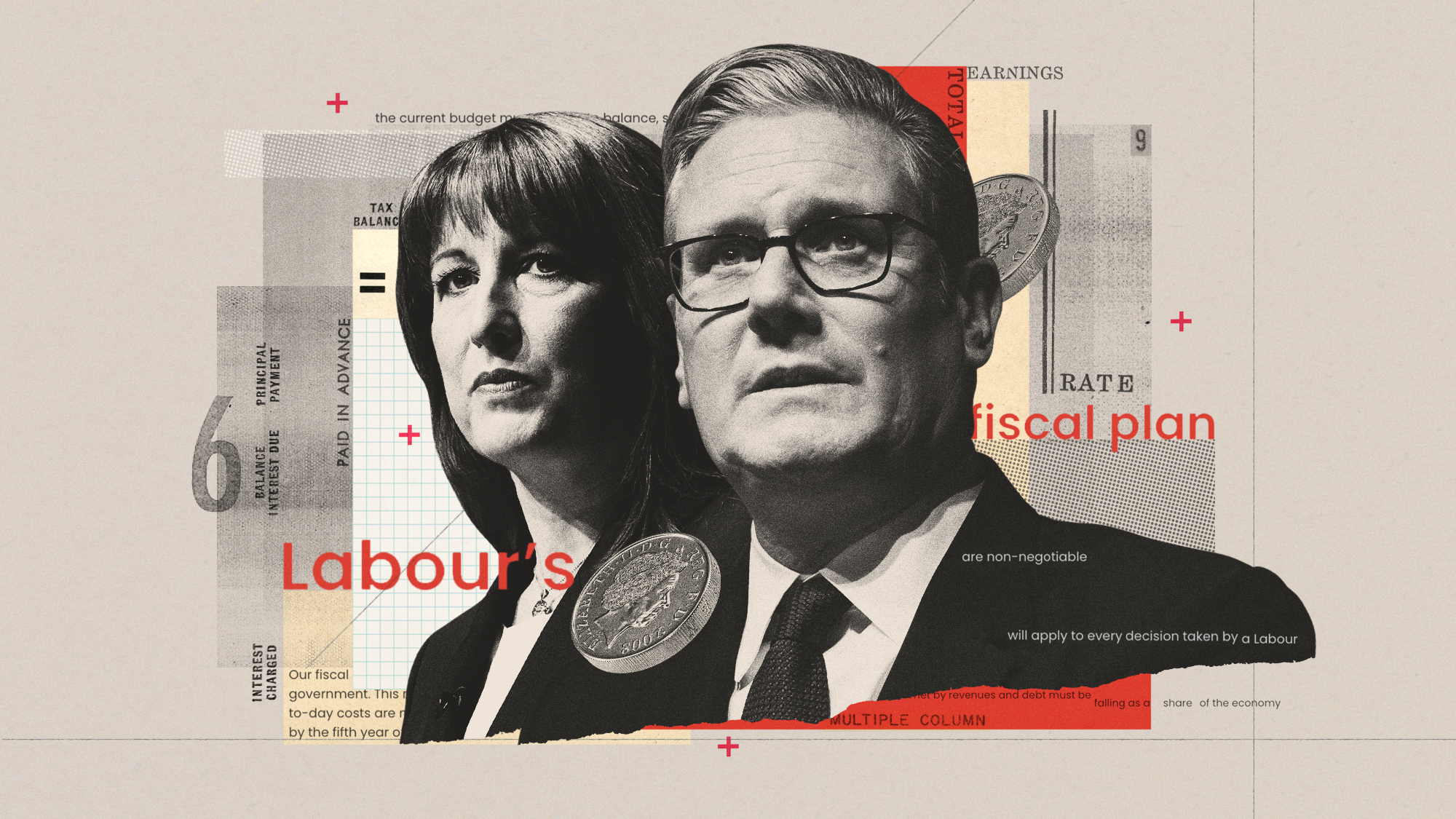

Should Labour break manifesto pledge and raise taxes?

Should Labour break manifesto pledge and raise taxes?Today's Big Question There are ‘powerful’ fiscal arguments for an income tax rise but it could mean ‘game over’ for the government

-

What are stablecoins, and why is the government so interested in them?

What are stablecoins, and why is the government so interested in them?The Explainer With the government backing calls for the regulation of certain cryptocurrencies, are stablecoins the future?

-

A newly created gasoline giant in the Americas could change the industry landscape

A newly created gasoline giant in the Americas could change the industry landscapeThe Explainer Sunoco and Parkland are two of the biggest fuel suppliers in the US and Canada, respectively

-

Trump's China tariffs start after Canada, Mexico pauses

Trump's China tariffs start after Canada, Mexico pausesSpeed Read The president paused his tariffs on America's closest neighbors after speaking to their leaders, but his import tax on Chinese goods has taken effect

-

Will the UK economy bounce back in 2024?

Will the UK economy bounce back in 2024?Today's Big Question Fears of recession follow warning that the West is 'sleepwalking into economic catastrophe'

-

Interest rates rise to 5.25% for first time in 15 years

Interest rates rise to 5.25% for first time in 15 yearsSpeed Read Inflation is slowing but at 7.9% it remains well above the Bank of England’s 2% target

-

Five options to get the UK back to 2% inflation

Five options to get the UK back to 2% inflationfeature Some economists believe alternatives to raising interest rates are in the country’s best interests