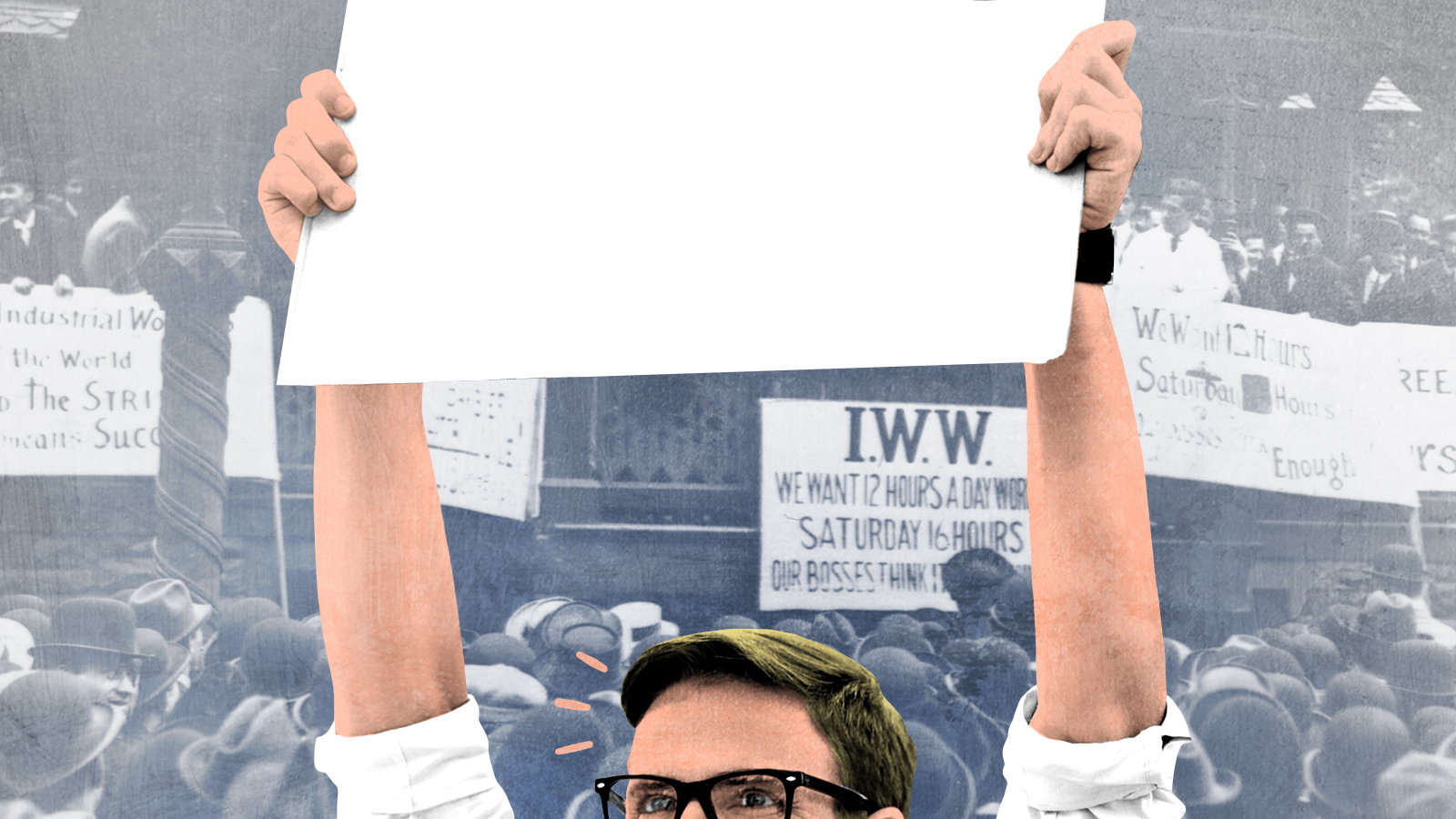

The pretend proletariat

Are the elites confusing themselves with labor?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What are the sources of political instability? Conventional wisdom holds that unrest starts at the bottom. It makes sense, that those who derive the fewest benefits from a particular order would want the biggest changes. Freedom, as the song goes, is just another word for nothing left to lose.

But some scholars of social movements give a counterintuitive answer. Radicalism appeals less to the absolutely downtrodden, in this view, than among those whose status and expectations outstrip their access to power. In an argument that's recently entered public discussion, the historian Peter Turchin dubbed this phenomenon "elite overproduction".

I've often thought of Turchin when reading about the revival of organized labor. After decades of declining membership and influence, labor unions are enjoying unfamiliar attention from the media and heightened interest from workers. Successful organizing drives at Amazon, Starbucks, and other prominent companies aren't the only signs of new strength. Despite a slowdown related to the pandemic, the number of major strikes is heading up as well.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But this isn't the labor movement that senior citizens might remember from its midcentury peak — and the rest of us imagine based on films like The Irishman. Unlike those sensationalized but not entirely misleading depictions of tough guys with shadowy criminal associations, the new unionism has a distinctly upper middle class quality.

In some cases, that change is evident in the type of workers who sign up. Defying stereotypes of gritty picket lines, the strikers of 2021 included editorial staff at The New Yorker and graduate students at Columbia University. Unions in media and the academy aren't unprecedented — the first national union of journalists was founded in the 1930s. Still, there's a certain irony in the fact that about a quarter of the 400,000 current members of the Union of Autoworkers–the archetypal industrial union — work at universities.

Downward mobility seems to be changing labor activism in more intuitively receptive sectors, too. The New York Times reported on Wednesday that college-educated workers played key roles in successful organization drives at Amazon, Starbucks, and the sporting-goods retailer REI. You can find support for Turchin's overproduction thesis in the quotes from college and even master's graduates who expected to work as salaried professionals in prestigious fields, but found themselves earning hourly wages and wearing company uniforms.

On the surface, these developments are promising for Democrats. In the most immediate sense, they offer a rare source of enthusiasm at the local level, where energy that had been directed against Donald Trump has mostly dissipated. Renewed connections with organized labor offer an opportunity to pivot away from increasingly unpopular associations with criminal justice reform (even when they don't rise to the level of "defund the police"), ideological experiments in education, and lax border enforcement. Moderates in the party are said to be pleading with the White House to emphasize economic concerns over cultural ones — although the return of stagflation makes that seem like merely swapping one electoral poison for another.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the changing character of the labor movement also gives reasons to doubt that unions can restore the left's fortunes. For one thing, the numbers don't add up. Despite highly publicized victories, the unionized portion of the private-sector labor force continues to drop. While the share is higher in the public sector and some industries, overall union density for non-government workers is just 6.1%. Even if a comeback is in progress, that's a very low starting point.

More important, though, the prominence of college graduates in the new school of labor activism could make it difficult to find the sort of broad coalition that Democrats enjoyed during the heyday of organized labor. The somewhat incongruous enthusiasm of highly credentialed editorial assistants, graduate students, and non-profit employees might signal a restoration of class consciousness — or just alienate potential allies. Like the presidential campaigns of Bernie Sanders, the version of organized labor that's become fashionable recently risks becoming a kind of role-playing rather than a genuine working class movement.

You can see the electoral consequences of that dynamic in former bastions of the labor movement. Longtime Democratic incumbents in states like Ohio are sinking under the weight of a national agenda that seems hostile to fossil fuels, heavy industry, and the cultural preferences of the white working class. That's not necessarily a problem in service fields or in cities like New York, where a unionization vote at a second Amazon warehouse is in progress. But it's likely to be an obstacle in "brown" enterprises and the old industrial heartland.

Which brings me back to Turchin. Not simply organic resistance from the lower strata of American life, the new unionism is also a protest of surplus elites against an increasingly ossified power structure. That doesn't mean it's doomed — if Turchin is right, the revolt of the elites can be even more disruptive than the demands of the genuinely poor or exploited. If they want to be successful, though, the new faces of organized labor need to prove they're more than dilettantes in proletarian drag.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.