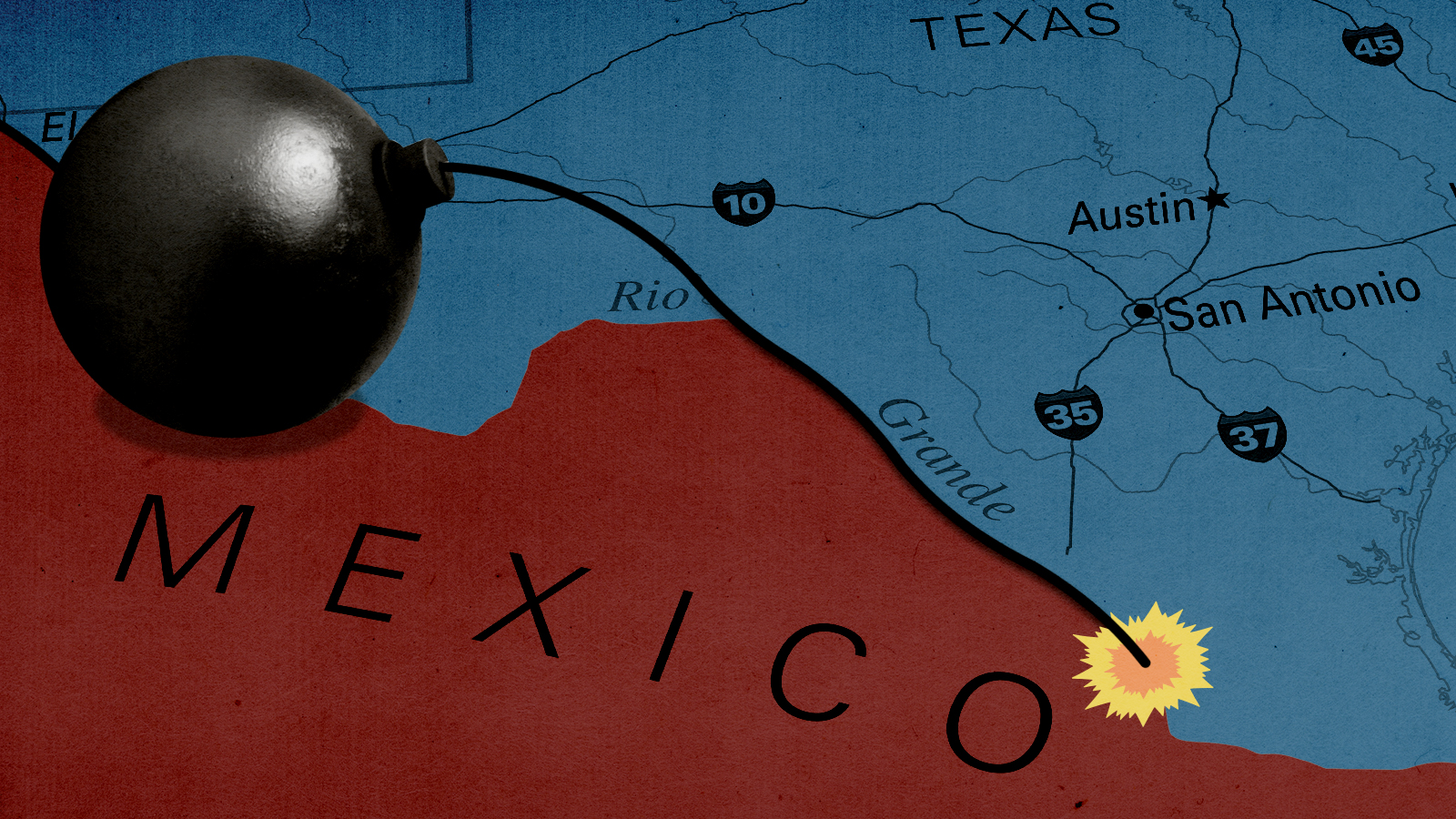

We can't keep playing hot potato with the southern border

A flood of immigrants will follow when Title 42 expires. Will Congress act?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Joe Biden is holding yet another hot potato. On May 23, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention directive that permitted the Department of Homeland Security to immediately expel asylum seekers at the southern border will expire. As administration officials admit, the revocation of "Title 42" authority granted while Donald Trump was president is likely to encourage a surge of migrants large enough to overwhelm processing capacities. If that happens, tens or hundreds of thousands of people from over the world will be released into the United States, under the theoretically binding but loosely enforced requirement to attend a hearing at some point months or years in the future.

That's more bad news for an administration reeling from the combination of rising inflation and crime, which are undercutting its popularity even among loyal Democrats. Voters dislike chaos and object to the appearance that the laws are not being applied fairly. Aware of the political risks, the administration defended the policy in court last year despite the objections of pro-immigration activists.

Strictly speaking, it's not the White House that decided to end the expulsion policy. Instead, the nominally independent CDC is revising an expert determination that triggered enforcement by the executive branch. That's why a lawsuit by Republican-led states that seeks to block the change focuses on administrative procedure. The filing submitted on Monday emphasized the social dangers of admitting more migrants, but the legal argument is based on a provision of the Administrative Procedure Act that requires a public comment period for certain kinds of rule-changes.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The appropriate level and kind of immigration are controversial questions that draw on deeply-held opinions about national identity, the moral implications of poverty and oppression around the world, and economic trade-offs. For just that reason, though, it's crazy to outsource major decisions to administrative agencies. Critics, including some moderate Democrats as well as Republicans, are right to argue that Biden is implementing a substantive policy change with only tangential connection to public health. Instructions to ICE officials to dismiss ostensibly low-priority deportation cases strengthen the case that Biden's preparing a de facto amnesty without taking responsibility for the consequences.

On the other hand, the pandemic was little more than a pretext in the first place. Trump officials started looking for powers to reduce immigration almost as soon they entered the White House. In the early days of the administration, flu and mumps were suggested as possible justifications for a crackdown at the border. Not until COVID, though, was any outbreak serious enough to convince relevant agencies of a genuine public health risk (a good dose of political pressure was likely part of the mix, too).

Pendular shifts between lax and rigorous control is bad for Americans because it exacerbates the sense that public policy is beyond democratic accountability and encourages polarization. It's also bad for would-be immigrants, who are tempted to risk their lives only to find that even the best case scenario involves years or decades in legal limbo. Administration officials including the hapless Vice President Kamala Harris blame "root causes," including climate change and political corruption for encouraging migrants to try their luck at the border. The reality is simpler: the United States is a rich country in a hemisphere and world with many poor countries. As long as that's the case, large numbers of people are likely to try any means at their disposal to gain entry.

But ultimate responsibility for the mess doesn't lie with civil servants, political appointees, or even with presidents, though. It lies with Congress, which has been recognized as the basic authority since the late 19th century, when the federal government took over the patchwork of powers previously exercised by the states to impose a series of laws that restricted Chinese immigration.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The modern era of immigration was inaugurated more than half a century ago by the 1965 Hart-Celler act, which eliminated the system of national quotas established after World War I. Despite a series of extensions and updates through the mid-90s, the main statutes haven't been updated in more than 25 years. The contradictions and shortcomings of that antiquated system are legion (this "roadmap" illustrates the mindboggling complexity of acquiring a green card). Particularly relevant to the Title 42 debate, is increasingly broad eligibility to claim asylum. Contrary to the usual rhetoric, people who present themselves at the border and request protection are not in the country illegally — at least until a court hears and rejects their case for asylum. But they are trying to squeeze through a Cold War loophole that was never intended as an permanent avenue of mass migration.

The explanation for Congress' inaction aren't hard to understand. As on so many other issues, it's easier to defer to the executive branch and the courts than to risk taking an unpopular stand. The combination of intentional gerrymandering and voluntary residential sorting also helps. With Congressional districts increasingly homogeneous, members of Congress have to worry more about primary challenges from party and ideological extremes than they do about satisfying the median voter. Legislators with long memories also recall the failure of the Comprehensive Immigration Reform bills of 2006. Despite strong support among the bipartisan elite, the measures foundered on opposition from conservatives, who believed the proposal made legal status too easy and doubted that the enforcement provisions would ever be realized.

No deal is sometimes better than a bad one. On immigration, though, legislative failure has led to the worst of both worlds. Looking for elusive center ground, Barack Obama stepped up deportation of illegal immigrants who committed crimes and extended legal protection to so-called "Dreamers" brought the US as minors and migrants from Haiti and other countries where he deemed return too dangerous. Use of those discretionary powers helped provoke the backlash that was central to Trump's 2016 campaign. Yet, existing law didn't grant Trump unequivocal authority to keep his promises to ban Muslims or seal the border. So he too relied on administrative workarounds, like the original Title 42 directive, that are vulnerable to litigation on procedural grounds as well as to reversal by successors in office.

The result is a permanent crisis that already helped end one administration (remember the "family separation policy"?). With Biden's signature combination of ineptitude and bad luck, it may help end another. That's a feature, not a bug, for the activists, ideologues, and strategists who know that oscillating panics about draconian enforcement and open borders drive clicks, donations, and votes. But Americans and immigrants alike deserve clear rules set by elected representatives in open votes--the way important choices are supposed to be made. Only Congress can make that happen.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.