China’s single mothers are teaming up

To cope with money pressures and work commitments, single mums are sharing homes, bills and childcare

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

China’s marriage rate is at record lows and its divorce rate is on the rise – but at least some of the country’s singles are teaming up.

As the cost of living intensifies, single mothers are “searching for a new kind of partner: each other”, said The Guardian. Women are posting online in search of “like-minded parents” to share both a home and childcare responsibilities.

“I’m hoping to find another single mum to share an apartment with, so we can take care of each other,” said a popular post on social media platform Xiaohongshu, known in English as RedNote. “If our children are around the same age, that would be even better – they can be companions. Those raising kids alone know how tough it is; sometimes you’re so busy, you barely have time to eat.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Acute strain

There are about 30 million single mothers in China, according to its Ministry of Civil Affairs. When parents divorce, “only one in six fathers chooses to raise their children”, said China Daily. That leaves more than 80% of those families led, solo, by a woman.

“Society’s support for single mothers remains insufficient,” said psychologist Li Jiao. Often they must contend with “internalised self-doubt, due to societal bias”, as well as “deep guilt over their children’s well-being”. A 2018 report found that more than two-thirds of single mothers are “hesitant to disclose their single-parent status”, for fear of being “judged or criticised”.

“The strain is acute,” said Sixth Tone. Long working hours “clash with rigid school schedules” – many mothers are left “sprinting between office desks and classroom gates”. Despite legal obligations, some ex-husbands refuse to pay child support, and state welfare is minimal. Government data shows that a significant proportion of single-mother families in developed cities live below the poverty line.

But, in recent years, social media platforms “have become lifelines, where women trade advice, pool expenses and, in some cases, find one another”. Some “roommate mums” simply split the rent but “others share school pickups and grocery runs, piecing together a version of family that is less solitary, less precarious, and a little more possible”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

‘Similar values’

Single mothers Zhu Danyu and Fei Yuan have lived together with their daughters since 2022. They run a joint business from their home in Nanjing. “We both know very clearly why we’re together – it’s about sharing and managing the risks and pressures of life,” Zhu told The Guardian.

They met through their work but, “over time, we realised that we shared similar values and got along really well,” said Fei. “Our personalities also complement each other. I’m more detail-oriented and love keeping things tidy, but I can’t cook. Danyu, on the other hand, is a great cook and loves making meals for the kids.”

There are of course “snide online remarks and rumours” about relationships like theirs, said the paper. Women in informal flat-sharing arrangements also “lack legal protections”, and some have talked online about “arrangements collapsing after children didn’t get along, or financial imbalances taking their toll”.

“This current reliance on ad hoc, digitally organised support highlights a major failure in the state’s welfare provision for safeguarding children and supporting parents,” said Ye Liu, an international development expert at King’s College London.

But many say their children are the “biggest beneficiaries” of the arrangement, said The Guardian. “Through spending time together, all three have become more outgoing and confident,” said Fei. “That’s the first big change I’ve noticed. The second is that they’re now surrounded by double the love.”

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff war

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff warSpeed Read The agreement will slash tariffs on most goods over the next decade

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

The app that checks if you are dead

The app that checks if you are deadIn The Spotlight Viral app cashing in on number of people living alone in China

-

Hong Kong court convicts democracy advocate Lai

Hong Kong court convicts democracy advocate LaiSpeed Read Former Hong Kong media mogul Jimmy Lai was convicted in a landmark national security trial

-

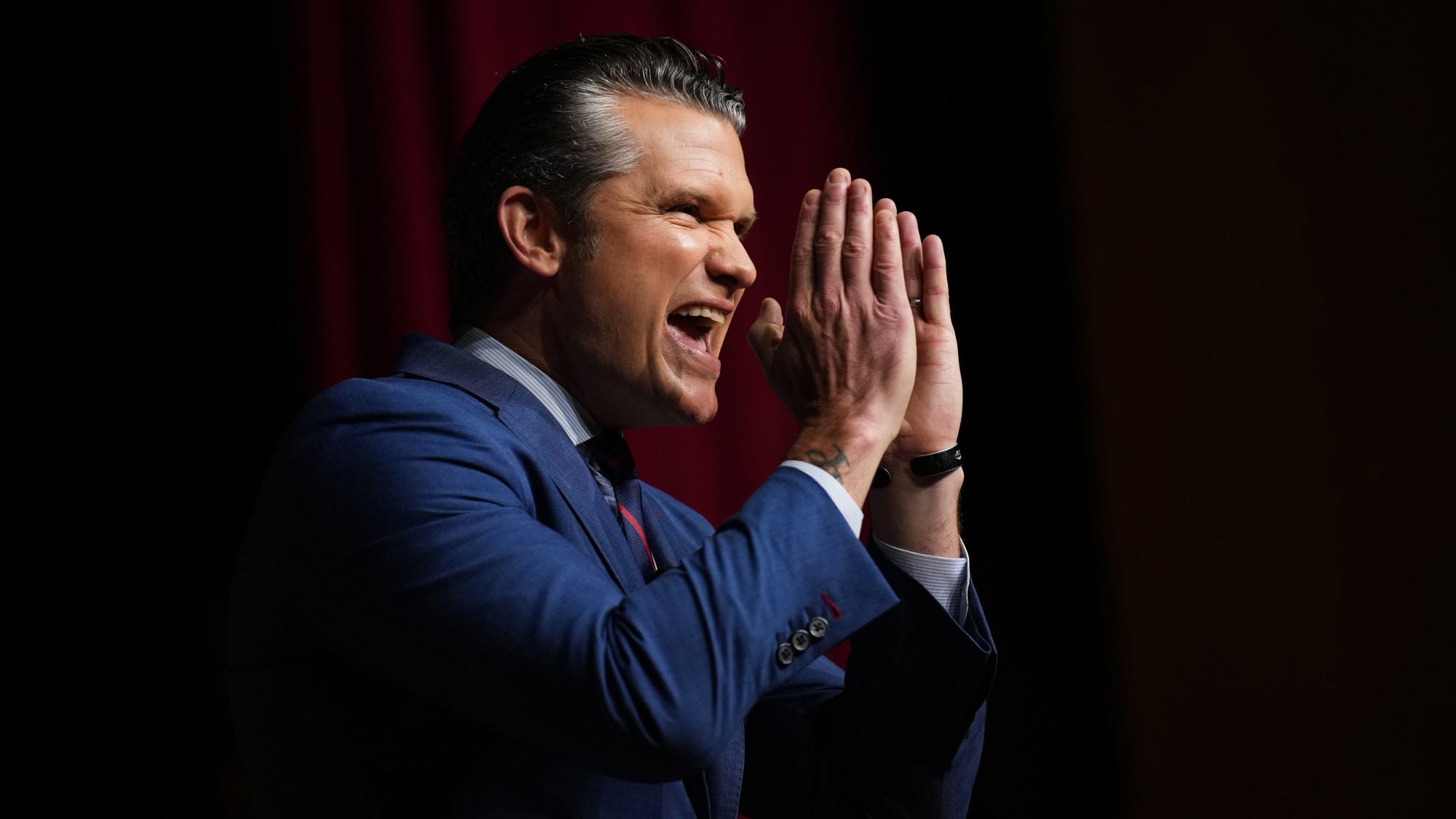

Remaking the military: Pete Hegseth’s war on diversity and ‘fat generals’

Remaking the military: Pete Hegseth’s war on diversity and ‘fat generals’Talking Point The US Secretary of War addressed military members on ‘warrior ethos’

-

Russia is ‘helping China’ prepare for an invasion of Taiwan

Russia is ‘helping China’ prepare for an invasion of TaiwanIn the Spotlight Russia is reportedly allowing China access to military training

-

'Axis of upheaval': will China summit cement new world order?

'Axis of upheaval': will China summit cement new world order?Today's Big Question Xi calls on anti-US alliance to cooperate in new China-led global system – but fault lines remain