The agony of Ukraine: how to keep Putin's Russia at bay

Pussy Riot shows the way: social media coverage is the best answer to Kiev's 'wicked problem'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

WHEN it comes to the crisis in Kiev and the agony of Ukraine, the word 'complex' is bandied freely by pundits far and wide.

Sure, Ukraine is a deeply divided, ethnic mix - but, frankly, not that mixed. More than three-quarters of those who live there are Ukrainian, under 18 per cent are ethnic Russian, and under five per cent are of other stock, including Greek, Turkish and Jewish.

Ukraine was one of the richest, and at times most reluctant, components of the USSR. Now, Vladimir Putin wants it to be a partner of his post-Soviet imperium through a customs union, sweetened by the offer of cut-price Russian gas.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Accordingly President Viktor Yanukovych chose the Russian union against the EU offer of association and a generous trade deal.

What Yanukovych didn't bargain for was the accumulation of protest that would greet his decision. This week it has led to running battles between the state police, who have resorted to sniper rifles and light machine guns, and the protesters who are becoming increasingly armed. And a death toll of 75.

From Thursday night's events, it is clear that the Interior Ministry forces and the police can no longer hold the capital. Overnight they set up sandbagged sniper positions in the upper floors of the president's office to make a last stand.

On the streets, activists have been forming 'hundreds' - sotni - a traditional term for a unit of Cossack cavalry. Other groups of nationalists have emerged in the protests such as Patriots of Ukraine, Trident and White Hammer under the umbrella of the Right Sector coalition.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Some trace their lineage back to the wartime nationalist Stepan Bandera, who declared an independent state of Western Ukraine as the Soviet forces retreated in 1941 - only to be captured and imprisoned by the invading Germans.

Romano Prodi, the former president of the EU commission and ex-prime minister of Italy, roundly condemned the protesters' use of firepower and violence in Thursday's New York Times, but cogently argued that this was no excuse for Yanukovych to call on his friend Putin to help out by sending in Russian military muscle.

Probably just as disastrous for Yanukovych would be to order in Ukraine's own army, traditionally neutral, as opposed to the police and security forces.

He has been shuffling appointments in the army's high command over the past three months, in order to get his men in place should he decide to declare martial law. But Ukraine's army, a byword for corruption and graft when it was deployed alongside Nato forces in peacekeeping in the Balkans, is deeply divided. It is thought it would split if ordered onto the streets, with up to a half going over to the protesters.

In the new geopolitical jargon, there are 'wicked problems' - that is, problems with no solution - and 'complex puzzles', ones that may have some way out, however tortuous and difficult it proves to be. Ukraine this weekend is teetering between the two.

Yanukovych appears to have offered some respite by offering elections. But a simple rerun of what happened in 2010 - elections Yanukovych won - will not suffice. A wholesale constitutional overhaul is required with representation and rights of minorities and parties guaranteed.

There must also be a declaration of non-interference from Moscow, Washington and Brussels. In the meantime, the foreign ministers of Europe, led by Laurent Fabius of France and Radislaw Sikorksy of Poland, must hang on in there in Kiev as they have much of this week, quite literally.

For all the bluster, the position of Vladimir Putin is not as strong as it might appear. This is not like Prague in 1968 or Georgia in 2008 when Moscow could deploy its tank columns almost without prejudice. Given the chronic state of separatist and Islamist insurgency in the Caucasus, not to mention Putin's internal security problems, Russian military interference is surely unrealistic.

Ukraine is now in the grip of spontaneous communal combustion - modern versions of jacqueries (medieval French peasants' revolts) - in more than half a dozen major centres which the Russian military wouldn't be capable of controlling, shy of putting in a force of more than 100,000.

But the biggest warning to Putin as to why this isn't Prague '68 or Georgia '08 is given eloquently by Maria Alyokhina, founder member of Pussy Riot, about her arrest in Sochi, printed today in the New York Times.

"This week in Sochi, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, another Pussy Riot member, and I were detained three times and then, on Wednesday, assaulted by Cossack (pro-Russian this time) militiamen with whips and pepper spray. Mr Putin will teach you how to love the motherland."

The images of the punk rockers assaulted by whip-wielding Cossacks has gone viral on YouTube and social media, as has footage of Kiev's bloodied protesters and machine-gunning snipers. Putin and Yanukovych should know that this is what they're up against.

is a writer on Western defence issues and Italian current affairs. He has worked for the Corriere della Sera in Milan, covered the Falklands invasion for BBC Radio, and worked as defence correspondent for The Daily Telegraph. His books include The Inner Sea: the Mediterranean and its People.

-

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’the week recommends The pasta you know and love. But ever so much better.

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

Buddhist monks’ US walk for peace

Buddhist monks’ US walk for peaceUnder the Radar Crowds have turned out on the roads from California to Washington and ‘millions are finding hope in their journey’

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

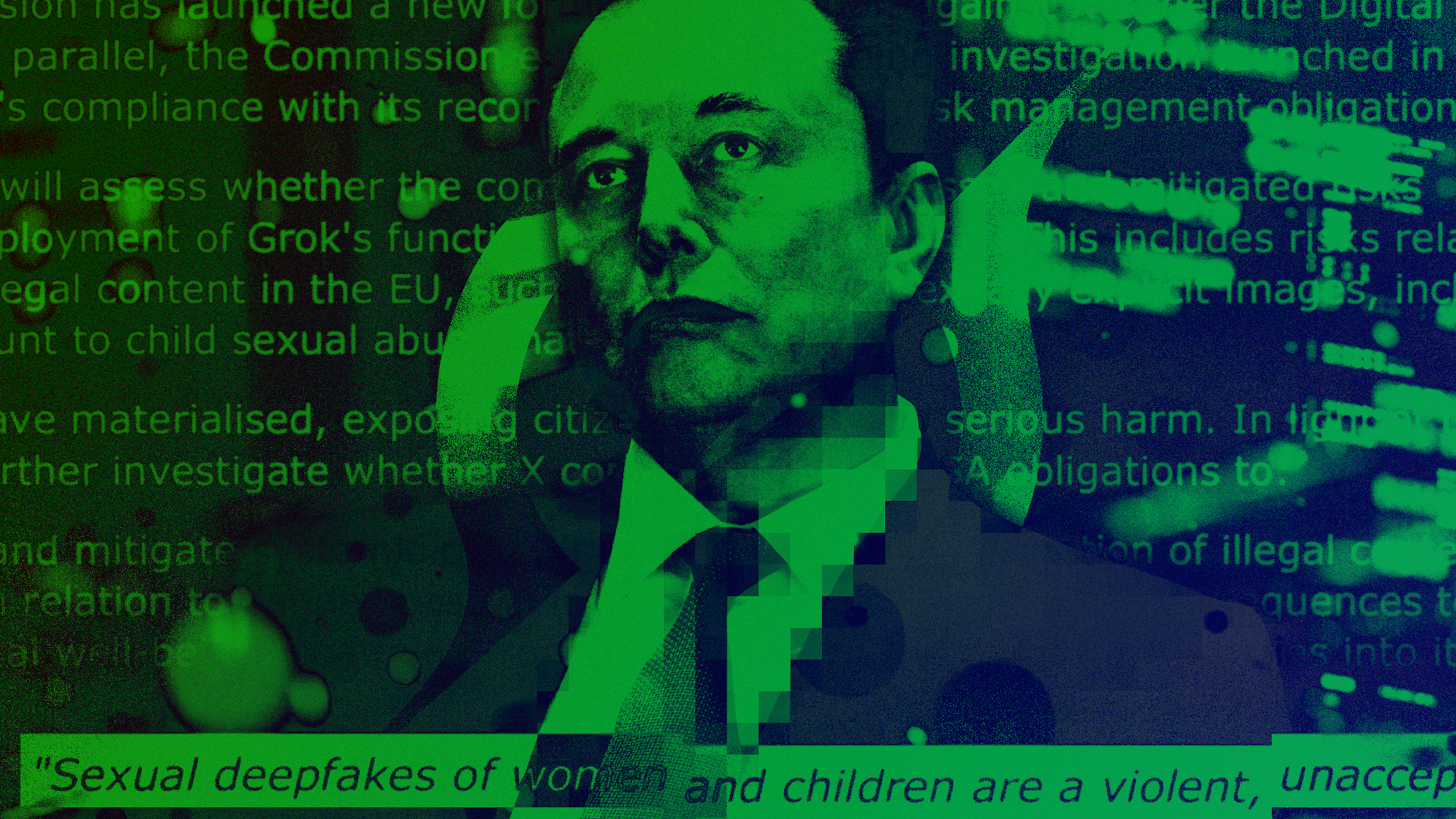

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probe

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probeIN THE SPOTLIGHT The European Union has officially begun investigating Elon Musk’s proprietary AI, as regulators zero in on Grok’s porn problem and its impact continent-wide

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

The rise of the spymaster: a ‘tectonic shift’ in Ukraine’s politics

The rise of the spymaster: a ‘tectonic shift’ in Ukraine’s politicsIn the Spotlight President Zelenskyy’s new chief of staff, former head of military intelligence Kyrylo Budanov, is widely viewed as a potential successor

-

Europe moves troops to Greenland as Trump fixates

Europe moves troops to Greenland as Trump fixatesSpeed Read Foreign ministers of Greenland and Denmark met at the White House yesterday