Will the far-right prevail in France this weekend?

President Macron has taken to the world stage, but slipped in the polls at home

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In a recent column about the landslide victory for Viktor Orban's Fidesz Party in Hungary's election last Sunday, I warned Western liberals and progressives against attributing the outcome entirely to electoral mischief and media manipulation by the incumbent. The truth is that the populist-nationalist message of Orban and his party appeals to lots of voters outside the capital of Budapest. That's consistent with electoral results across the democratic world, where in recent election cycles people in rural areas and small towns have begun banding together in opposition to urban progressivism and in favor of a harder-edged, right-wing mode of politics.

In the first round of France's presidential election this Sunday, the pattern may well be repeated in a context where it would be impossible to attribute the results to an incumbent giving himself an unfair advantage in the contest.

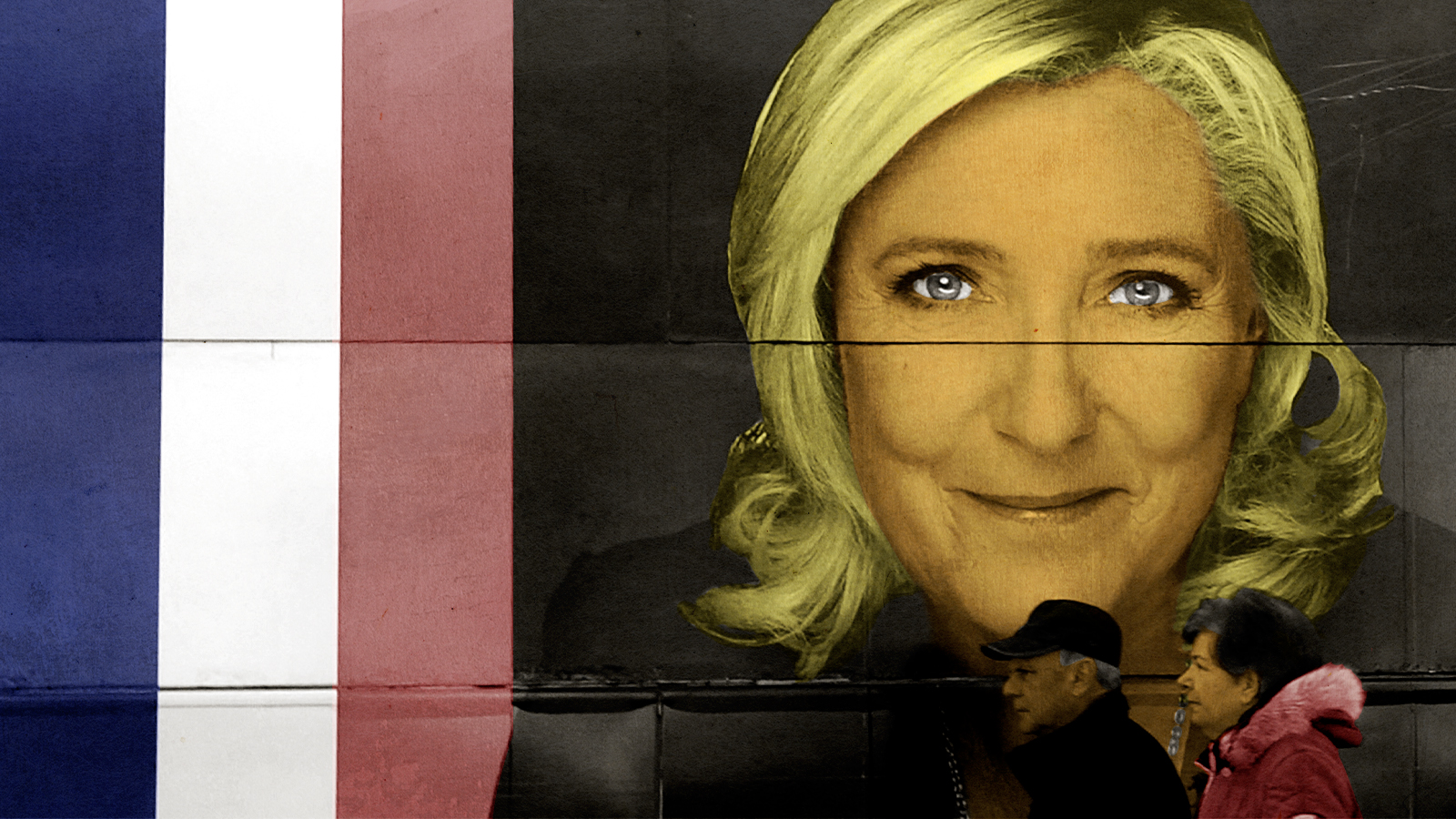

French President Emmanuel Macron of the centrist Forward party leads the polls, but he's been sinking for the past three weeks, while Marine Le Pen of the far-right National Rally party has been rising. Aggregate polls currently place Le Pen 4 to 5 points behind Macron with the gap closing, while some more recent polls show her just 2 points behind. This reproduces the dynamic that prevailed in the run-up to the dual political earthquakes of 2016: the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and Donald Trump's victory against Hillary Clinton in the U.S. presidential election.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Could France and the wider democratic world be close to another upset victory for the antiliberal right?

A narrow win for Le Pen on Sunday would be significant mainly for its symbolism. Assuming no candidate prevails with a majority of the vote (and no one is remotely close to accomplishing that), the second, decisive election will be held two weeks later, on April 24, between the first- and second-place finishers from April 10. That's when things could really become ominous.

In some ways, this would be a rerun of the presidential election five years ago, when Macron beat Le Pen in the first-round vote by 2.7 points, setting up a second-round showdown. In the intervening weeks, two important things happened. First, Macron mobilized an anyone-but-the-fascist coalition in support of himself and his newly formed centrist party. This anticipated the similar cross-ideological coalition that unseated Benjamin Netanyahu in Israel last year as well as the one that tried and failed to do the same against Orban in Hungary last Sunday.

Second, Le Pen did poorly in her single debate against Macron, coming off as arrogant and ill-informed throughout their exchange. The conviction that she was unready to assume the office of the presidency contributed to a last-minute collapse in the polls that delivered a landslide victory for Macron, who prevailed with two-thirds of the vote (66 to 33 percent).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

If Macron faces Le Pen in the second-round vote this time, he will no doubt attempt to reassemble his anti-fascist coalition from 2017. But we have reason to worry about its likely effectiveness. For one thing, Le Pen changed the name of her party (from National Front to National Rally) in the wake of her defeat five years ago and has been remarkably successful at reforming its image by distancing herself from the toxic legacy of her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, who led the NF from 1972 to 2011. Some of this change can no doubt be attributed to Le Pen's political skill, but the presence of far-right firebrand Éric Zemmour in the race may have helped as well, making Le Pen appear tame and responsible by comparison.

But a broader anti-establishment shift of the French electorate may also be playing a role. The other candidate surging in the polls just days from the first-round vote is the leftist Jean-Luc Mélenchon, currently polling at 16 percent, behind Macron at 26 percent and Le Pen at 22 percent. Center-right candidate Valérie Pércresse, meanwhile, sits at just 8 percent after a polling collapse that's been unfolding over the past several months.

If Macron and Le Pen face off in the second round, where will Mélenchon's first-round voters go? Will they rally to Macron's side as many of them did five years ago in order to prevent the National Front from prevailing? Or will at least some of them trade a left-wing anti-establishment candidate for a right-wing one with a new name? Or will they simply stay home, depriving Macron of voters he will desperately need on April 24? With current head-to-head polling showing the second-round vote between Macron and Le Pen a dead heat, the incumbent is going to need all the votes he can get.

But where will they come from? To prevail, Macron will be counting on support from Green Party and Socialist Party voters, currently polling at 5 and 2 percent respectively, along with as many of Mélenchon's first-round voters as he can muster, plus some right-leaning votes. How can he lure the latter away from Le Pen? He can try to portray her as an extremist. And he can attempt to fluster her in their televised debate, hoping to re-enact events from 2017.

But beyond that, it's far from clear what he can do. Five years ago, Macron was an untested proposition — a young, charismatic, and articulate neoliberal leading a new party. That made him a suitable screen onto which a restive nation could project its future hopes. But now he represents the status quo in a country increasingly dominated by polarizing political and cultural discontents and perhaps eager for a different kind of future.

That makes the upcoming election in France the latest high-stakes contest over the shape of politics in the liberal-democratic world. Viktor Orban's decisive victory in Hungary last weekend felt like a dispiriting punch to the gut for many liberals and progressives across the West. But that's nothing compared to how they will feel if French voters deliver the presidency to Marine Le Pen later this month.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military