What Hungary can teach Democrats about democracy

Orbán mainly won because he's popular. Americans still confused about Trump should pay attention.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the aftermath of Donald Trump's surprise defeat of Hillary Clinton in 2016, many on the center-left insisted the problem was our institutions: the illegitimate Electoral College, the dangerously anti-democratic Senate, our fundamentally unfair district maps and voting procedures. Many of these objections are perfectly reasonable, but none are sufficient to explain how Trump won — just as the reform of any or all of them would be insufficient to ensure he or a populist-nationalist successor couldn't win power in the future.

That's because Trump's very narrow win in 2016 (like his relatively narrow loss in 2020) was primarily made possible by his small-d democratic appeal to tens of millions of voters. He won — with a little help from the system's extra-democratic institutions — because many people liked him. But if Trump's center-left critics can't see how that could happen here, in their own country, perhaps they can see it in Hungary.

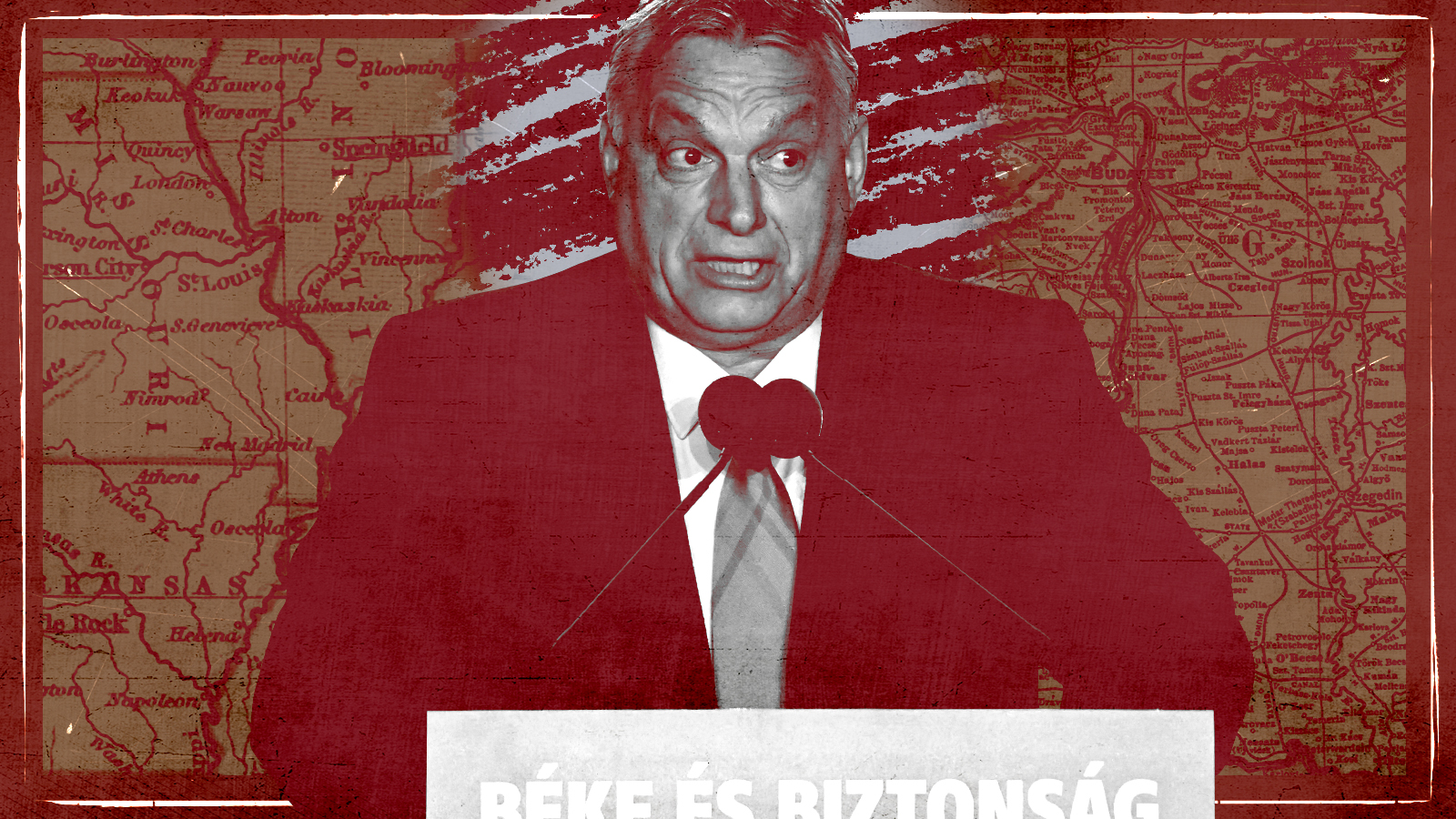

The solid victory of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán's Fidesz Party on Sunday has the populist-nationalist faction of the Republican Party feeling giddy about its prospects — but it's Democrats still confused about Trump who should be paying close attention to Orbán's democratic success.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Fidesz (in alliance with the Christian Democratic People's Party [KDNP]) won power in 2010 with about 53 percent of the vote. That earned the victors two-thirds of the seats in the Hungarian parliament, giving them sufficient power to write and approve a new constitution, which they promptly did. In the next election, in 2014, Fidesz-KDNP again prevailed by a large margin, this time a plurality of about 44 percent under a new electoral system that preserved the victors' two-thirds majority in a now-smaller parliament. Four years later, Fidesz-KDNP won around 48 percent of the vote and ended up, once again, with two-thirds of the legislature.

What made the most recent election this past Sunday unusual is that this time most of the opposition parties banded together to form United for Hungary, the kind of cross-ideological alliance that led to Benjamin Netanyahu's ouster in Israel last year. Though opponents of Orbán's rule hoped this approach might lead to electoral success — or at least a narrower victory for Fidesz-KNDP — that isn't how it worked out. With nearly all the votes counted, Fidesz-KDNP look to have won roughly 53 percent of the vote, most likely giving them two additional parliamentary seats, while the combined opposition finished 18 points behind at 35 percent.

But wait — Orbán won re-election in a landslide? How could that be? Haven't we heard for years that Hungary is no longer a democracy? That its elections might be free, but they certainly aren't fair? That the country is now governed by an "authoritarian regime" or possibly "soft fascism"?

The reality is more muddled than such breathless commentary would lead one to believe. Judged by the standards of American liberalism, many of Orbán's policies are odious, and his public rhetoric even worse. Orbán proudly describes himself as antiliberal and cultivates ties with like-minded conservatives throughout the Western world, especially in the United States, who reciprocate with fawning coverage. He is staunchly opposed to immigration. He has instituted ambitious pro-natalist policies. He has worked to ban gender studies from Hungary's universities and managed to expel a major university from the nation's capital. And he regularly emits unsubtle antisemitic dog-whistles — most recently in his victory speech on Sunday night.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All of that makes Orbán an enemy of liberalism. But what about democracy? There his record is more mixed, though the center-left might not want to admit the distinction. Various rules and regulations have made it more challenging than it once was for opposition parties to gain a fair hearing in the Hungarian media, most of which Fidesz and its allies control. Gerrymandering gives Fidesz an edge in elections. And by all accounts, the country is awash in corruption.

Add it all up and we're left with a picture of a country in which Fidesz and its allies enjoy certain electoral advantages. Orbán's party might be able to maintain majority control of the legislature while winning just 43 percent of the vote, for example, and thanks to media bias it will tend to have a somewhat easier time than any opposition party (or, as we saw on Sunday, even an alliance of multiple opposition parties) in reaching that level of support.

None of that is great for democracy. But is it bad enough to turn Hungarian elections into the kind of electoral farce we see in genuine dictatorships? Hardly.

For one thing, many political systems enhance the legislative margin of the winning party or coalition. (In the most recent election in the United Kingdom, for instance, Boris Johnson's Conservatives prevailed with 43.6 percent of the vote but won 56 percent of the seats in the House of Commons.) Then there were the polls, which in the run-up to Hungary's vote last weekend gave Fidesz a solid lead that broadly comports with election results. Turnout for the election, at nearly 69 percent, was healthy. And according to BBC, "More than 200 international observers monitored the election in Hungary, along with thousands of volunteers from across the political spectrum."

But perhaps the strongest bit of evidence in favor of considering Hungary's election free and at least partially fair is the regional results. The opposition United for Hungary lost almost everywhere in the country except for Budapest, the capital and largest city. The pattern of Fidesz winning nearly everywhere but the country's urban center began with its first victory 12 years ago, before Orbán and his party took over the government and began to take control of the media. And a similar pattern of populist forces rooted in small towns and rural areas doing political and cultural battle with urban progressives has also appeared in the United States, the U.K., France, and many other countries around the world. It is among the most distinctive characteristics of politics in our moment.

Viktor Orbán has done some bad things over the past 12 years to give himself and his party a marginal boost in elections. But his ability to mobilize the non-urban parts of his country in support of his government is far more significant and the true secret of his political success. He won — with a little help from the system's extra-democratic institutions — because many people liked him.

That's a lesson America's Democratic Party, increasingly reliant on the votes of the country's cities and quick to focus on institutional sources of its electoral struggles, desperately needs to take to heart.

The greatest threat to liberalism in America isn't the prospect of Republicans cheating their way back to power. It's the prospect of them winning fair and square.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ book

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ bookThe Week Recommends Gabriel Sherman examines Rupert Murdoch’s ‘war of succession’ over his media empire

-

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House role

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House roleIn the Spotlight Olsen reportedly has access to significant US intelligence

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump