A 150-year-late Gettysburg Address retraction and 5 other ridiculously belated apologies

It's apparently never too late to say you're sorry

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

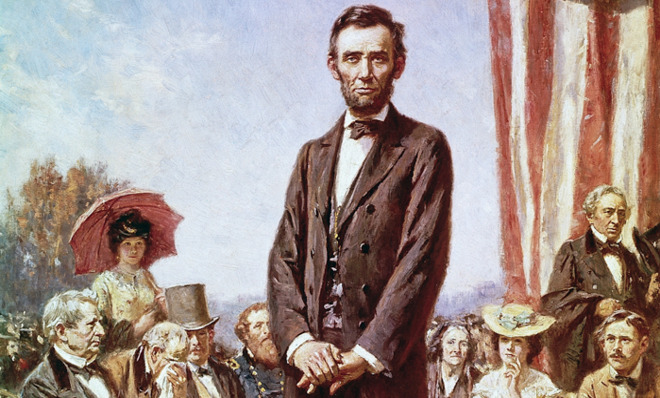

On Thursday, The Patriot-News of Harrisburg, Pa., issued a correction. Now, newspapers do this all the time. Usually, though, they don't wait 150 years. This retraction took the form of an editorial, formally recanting an infamous editorial by the paper's Civil War predecessor, The Patriot & Union, belittling Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address as forgettable flummery.

You can read the original editorial in The Patriot-News' retraction or the accompanying article explaining how the paper "earned itself an enduring place in history for having got Lincoln's Gettysburg Address utterly, jaw-droppingly wrong." (Short answer: Politics.) But here's the offending line:

"We pass over the silly remarks of the President. For the credit of the nation we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them and that they shall be no more repeated or thought of."

Today's editorial board decided to eat crow in style:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Seven score and 10 years ago, the forefathers of this media institution brought forth to its audience a judgment so flawed, so tainted by hubris, so lacking in the perspective history would bring, that it cannot remain unaddressed in our archives....

No mere utterance, then or now, could do justice to the soaring heights of language Mr. Lincoln reached that day. By today's words alone, we cannot exalt, we cannot hallow, we cannot venerate this sacred text, for a grateful nation long ago came to view those words with reverence, without guidance from this chagrined member of the mainstream media. The world will little note nor long remember our emendation of this institution's record — but we must do as conscience demands. [Patriot-News]

This isn't the most consequential apology, nor the most belated. Here are five other long-overdue corrections, issued for posterity or, as with The News-Patriot, because the offending institution is tired of getting grief for having gotten it so wrong:

1. The Catholic Churches: Nostra maxima culpa, Galileo

In 1632, the Vatican prosecuted Galileo Galilei for the heresy of asserting that the Earth revolved around the Sun, not vice versa. In 1633, faced with being burned at the stake, Galileo recanted (with the probably apocryphal aside "Eppure si muove" [And yet, it moves]). Even with his renunciation of his theory (and it being correct), one of history's most famous scientists spent the last eight years of his life under house arrest.

In 1992 — 359 years after his trial, and centuries after the scientific controversy had been settled conclusively (even Catholic schools started teaching that the Earth isn't the center of the universe in the mid-1700s) — Pope John Paul II admitted that the church had messed up. His mea culpa followed a 13-year investigation into the Galileo affair by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. The Catholic Church formally apologized to Galileo in 2000. Nobody has ever accused the Vatican of undue haste.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

2. America: Apologies for that slavery thing

By this point, everyone believes that the enslavement and forced labor of Africans and African Americans is a huge black mark on America's record. But it wasn't until six months after Obama's inauguration that America formally apologized for slavery.

On June 18, 2009, the Senate approved a resolution apologizing for America's 250 years of slavery and the subsequent period of racial segregation. "You wonder why we didn't do it 100 years ago," said Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), lead sponsor of the resolution. "It is important to have a collective response to a collective injustice." The House had passed a similar bill a year earlier, without a Senate clause stipulating that the apology doesn't authorize or support "any claim against the United States."

That thinly veiled dismissal of any discussion about reparations for the descendants of slaves — Japanese-Americans interred during World War II got $20,000 per surviving victim after Congress apologized to them in 1988 — scuttled the bill in the House. So Congress fervently apologized for slavery and Jim Crow laws — just not at the same time.

3. Australia: We regret trying to erase the Aborigines

On Feb. 13, 2008, Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, as one of his first acts in office, apologized to Australia's Aborigines and other indigenous people. He expressed contrition for the "the laws and policies of successive Parliaments and governments that have inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss on these our fellow Australians," especially the policies that led to "Stolen Generations" of Aboriginal children, with the goal of breeding the "color" out of the native Australians.

In June 2008, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper also apologized to indigenous Canadians, for policies dating from the 1870s to 1970s that removed children from their families and put them in Indian Residential Schools designed to convert them to Christianity and assimilate them into white Canadian culture. The U.S. Congress considered resolutions in 2008 to formally apologize to Native American tribes and tribal members, but the bills sputtered, possibly over concerns about reparations.

4. Fiji: Hey, sorry for eating that English missionary

In November 2003, the residents of Nubutautau, Fiji, held an elaborate ceremony to apologize on behalf of their ancestors for killing, roasting, and eating Rev. Thomas Baker in July 1867. Legend has it that Baker, a Methodist minister and missionary from England, broke a taboo by touching a Fijian chief's hair — though it may just have been that he was spreading Christianity and the Fijian elders didn't like that.

In any case, Baker and seven of his converts were ambushed one morning, beaten with clubs, cut up, roasted, and consumed by villagers. In their six-hour ceremony 136 years later, the descendants of the cannibals begged forgiveness from 10 Australian descendants of Baker. This wasn't just to salve guilty collective consciences: The Fijians believed that Baker's murder had cursed them.

Les Lester, Baker's 56-year-old great-great-grandson, called the ceremony a success. "The past is the past and we need to move ahead to the future," he said, as village chief Ratu Filimone Nawawabalavu wiped away tears. "I feel that the spirit of Thomas Baker is at rest."

Peter Tale, a Fijian government official, also tried to turn the page on Fiji's past, culinary and otherwise: "Many people were killed and eaten in the olden times. But we in this generation don't like it at all."

5. New York Times: Sorry, Lt. Schwenk

In May 2011, The New York Times corrected an obituary for a man named Milton Schwenk... who died in 1899. No, that's not a typo. The first problem with The Times' century-old obit? To start with, "Lt. M. K. Schwenk's first name was Milton, not Melton," says James Barron, who decided the record needed to be corrected. Also, he was born in Pennsylvania, not Georgia; his father didn't immigrate to the U.S.; and he went to the Naval Academy, which did not have fraternities, but was a member of Sigma Chi.

Why correct the record — and dig extensively into a long-dead man's life? Schwenk's great-nephew contacted The Times to point out their errors. Besides, says Barron, "if journalism is indeed the first rough draft of history, there is always time to revise, polish and perfect, even if pinning down the details about Lieutenant Schwenk after so many years turned out to be less than straightforward." RIP, Lt. Schwenk.

Correction: An earlier version of this article attributed the quote about the spirit of British missionary Thomas Baker being at rest to Fijian village chief Ratu Filimone Nawawabalavu.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day