Are teen pregnancies good for the economy?

Teen pregnancies are at historic lows. But that has economic repercussions.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

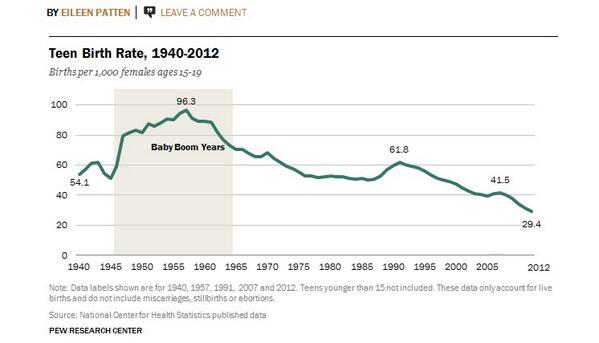

At Pew Research Center, Eileen Patten points out that "[t]he teen birth rate in the U.S. is at a record low, dropping below 30 births per 1,000 teen females for the first time since the government began collecting consistent data on births to teens ages 15-19":

[Pew]

What's changed? "The short answer is that it is a combination of less sex and more contraception. Teenagers have a greater number of methods of contraceptives to choose from," Bill Albert, the chief program officer of The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, told Time. He added, "The menu of contraceptive methods has never been longer."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Reducing teenage pregnancy has long been a matter of policy for the federal government, and the latest trends represent a policy victory for successive administrations who have tried to achieve that goal. While liberals and conservatives manage to find ways to disagree on issue after issue, teen pregnancy is one point on which they largely agree. Though they diverge on the means — many conservatives advocate abstinence while liberals tend to favor contraception — both sides happily shake hands on the common goal of reducing teen pregnancy.

The Department for Health and Human Services' (HHS) case against teenage pregnancy is as follows:

Compared with their peers who delay childbearing, teen girls who have babies are:

HHS also argues that the cost of teenage pregnancy falls disproportionately upon the taxpayer:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Teen childbearing costs U.S. taxpayers billions of dollars due to lost tax revenue, increased public assistance payments, and greater expenditures for public health care, foster care, and criminal justice services. [Department for Health and Human Services]

But there are some good reasons to question the orthodoxy on teenage pregnancy.

Over a longer time frame, teenage pregnancy may not correlate with poverty and welfare dependency at all. Duke University economist V. Joseph Hotz found in a 2004 study that by age 35, former teen moms had earned more in income, paid more in taxes, were substantially less likely to live in poverty, and collected less in public assistance than similarly situated women who waited until their 20s to have babies.

The bigger economic picture is that more people means more economic activity, from the first ultrasound, to the birth, to the costs of raising the child, to the child entering the labor force, at which point she will buy a home, pay taxes, save for retirement, etc. A larger population requires more infrastructure — homes, shops, roads, ports, schools, hospitals — the building of which creates jobs and stimulates the economy over a lifetime.

Economic growth is strongly correlated with population growth. And simply put, the earlier each generation goes forth and multiplies, the earlier the wider economy receives these benefits. Keeping up the birth rate has fallen to older mothers, but U.S. birth rates generally are falling, and are now lower than Russia's, a country once famed for its low birth rate.

It's no coincidence that the Baby Boom in the postwar era — which included a high rate of teen births — was one of great prosperity for America, with strong real GDP growth and robust wage growth. Kids cost money, and spending drives the economy. On the other hand, countries with declining populations, like Japan, have suffered from weak economic growth, which is exacerbated by smaller working age populations straining to support ever-larger numbers of retirees.

Of course, society has changed a lot since the 1950s and 1960s. In the West, teenage marriage is frowned upon in most communities. The median age for a first marriage for women was 20 in 1950 — it's now 26.

The underlying circumstances behind teen pregnancies have changed, too. Most teenage births nowadays come from unwed parents. In 1960, only about 15 percent of mothers between the ages of 15 to 19 were unmarried. Today, 89 percent of teenage births are to unmarried mothers.

So, it's obviously unrealistic to hope that the U.S. can return to the teenage birth rate of the Baby Boom. Our cultural norms and expectations have drastically changed. Dropping out of high school to have a child is a huge risk in today's world, where literacy and numeracy are highly prized in most fields of work. Weak wage growth, high youth unemployment, and a relatively weak economic recovery have made it more difficult for the young to support children, too.

Furthermore, the widespread availability of contraception, as well as the mainstreaming of college-level education, have given teenagers — of both genders — a far wider choice of lifestyle beyond having, raising, and providing for children. That wider freedom of choice gives individuals a greater opportunity to find the niche in the economy where they are happiest and most productive.

Perhaps there can be a balance between the robust economic growth of the Baby Boom, and the freedom of choice of modernity. One way could be to offer large additional economic incentives like tax breaks for married recent high school and college graduates to have children, while continuing to strongly discourage it among singletons still in school.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.