Sorry, GOP, tax cuts don't pay for themselves

But it wouldn't hurt the Democrats to claim that their priorities do

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As they prepare to take control of Congress, Republicans are looking to change the rules of the game. To lend budget-busting tax cuts the illusion of fiscal responsibility, conservatives would codify the notion that these cuts pay for themselves into congressional accounting rules.

Democrats should not allow this to happen. But if conservatives insist on fudging the numbers, liberals shouldn't shy away from making creative budgetary arguments of their own.

The accounting device promoted by the right is known as "dynamic scoring," and it's politically significant because of the basic policy positions of the two parties. Conservatives tend to favor tax cuts, which come at the expense of social services. Liberals tend to support increasing social services, which come at the cost of higher taxation.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But conservatives have an end-run around this dynamic. They point to the Laffer curve, an economic theory proposing that we can cut tax rates without sacrificing tax revenue, thus avoiding cuts to social services. This is because tax policy has dynamic effects on the macro-economy — that is, cutting tax rates incentivizes people (and particularly high-earners, who gain the most from tax cuts) to work harder, invest more, and generate more economic growth. As the economic pie grows larger, tax revenue can remain constant even as tax rates fall.

Though logical in theory, this idea hasn't really been borne out in practice. The Bush administration repeatedly predicted that tax cuts would boost overall revenue, but they assuredly did not. And they still don't, as Kansans have learned during Gov. Sam Brownback's "real live experiment" in conservative economics, which has only blown a hole in the state budget.

This is because any potential dynamic effects of tax cuts take a long time to materialize, which makes these future benefits extremely difficult to quantify today. And as Congress' authoritative accountant, the CBO is in the business of attaching hard numbers to would-be laws.

Understandably, the CBO has resisted the uncertain and speculative math of dynamic scoring. But the underlying argument still infuses and skews our political debate. Republicans feel less constrained when proposing tax cuts, while Democrats struggle to shore up revenue sources for government service proposals.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

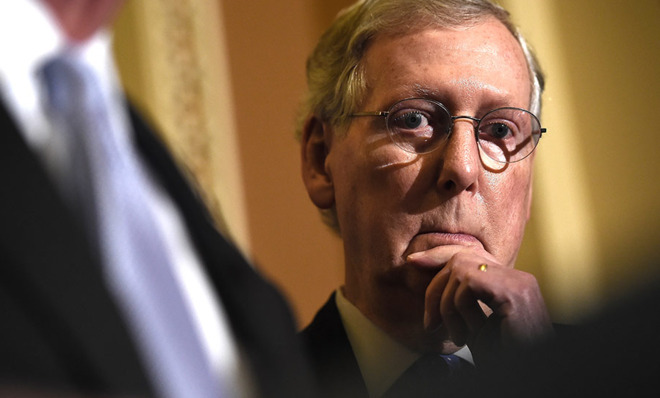

Ostensible fiscal conservatives like Sens. Mitch McConnell (Ky.) and John Kyl (Ariz.) argue that tax cuts need not be paid for at all because they are inherently good for the economy. "[T]here's no evidence whatsoever that the Bush tax cuts actually diminished revenue," McConnell contends, in spite of overwhelming evidence that these cuts diminished revenue at historic rates.

Yet these same Republican leaders still insist that spending on unemployment benefits be accounted for by cuts or tax increases elsewhere, even though there's little compelling economic reason to treat tax cuts and social insurance transfers like unemployment benefits differently. Both policies promote economic growth by increasing disposable income and thereby boosting consumption.

Liberals have largely failed to point this out and haven't effectively countered conservative attacks on these transfer programs. Contrary to what Speaker John Boehner (Ohio) says, there's no evidence that unemployment benefits reduce work ethic. And other transfer programs can be carefully structured to minimize any potential work disincentives.

Liberals can do more than play defense in these debates. They, too, can conjure creative arguments for how targeted spending programs can "pay for themselves."

Take liberal proposals for new or expanded transfer programs like refundable tax credits, child allowances, and other income subsidies. These relieve some of the strain on the budgets of low-income and middle-class Americans. More disposable income means more consumption, which generates higher economic growth and higher overall income, producing more tax revenue. By this logic, transfer programs could pay for themselves, too.

In fact, targeted transfers to the poor and middle class would likely give a stronger immediate jolt to the economy than would tax cuts for the wealthy. Compared with the wealthy, the poor spend a much higher share of each additional dollar of disposable income that they receive, providing greater stimulus to the economy. Policy measures that alleviate inequality are thus a boon for economic growth.

This isn't to say that liberals should sit back and let dynamic effects fund their policy priorities. Any responsible party must provide revenue sources for new tax or spending programs. But drawing on this rhetoric would level the playing field of our skewed politics. The parameters of our current debate — where liberal proposals must be paid for while conservative ones don't — are stacked against the interests of average Americans in favor of the wealthy.

Conservatives want to muddy the numbers for our lawmaking process. For the sake of a fair debate, liberals can and must show that two can play at that game.

Joel Dodge writes about politics, law, and domestic policy for The Week and at his blog. He is a member of the Boston University School of Law's class of 2014.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred