The Fed has a premature extractulation problem

It happens to a lot of central banks. But there are work-arounds.

The Federal Reserve just can't seem to get the job done. Since the financial crisis of 2008, America's central bank has repeatedly tried to stop its unconventional stimulus program — and each time has proven premature.

That looks to be happening again today. Just last month, the Fed finally finished tapering off its last round of quantitative easing, and the economy immediately started to slide toward deflation. If this continues, then the Fed may be forced to step back in with more stimulus. And if that happens, they really ought to consider a serious change in strategy.

Before I go further, what are we talking about? Quantitative easing (QE) is a deeply terrible name for a kind of monetary stimulus. The Fed buys long-term government bonds and other financial assets with new money. That will push down long-term interest rates and increase bank reserves, which then will hopefully be lent out. The details (see here for more) aren't as important as the overall point: to push money out into the economy with the goal of sparking growth and creating jobs.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

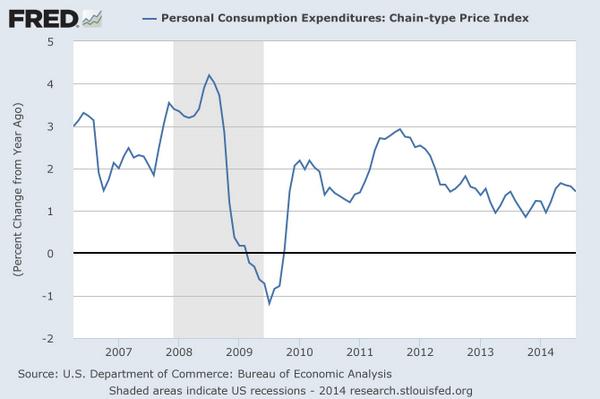

So let's wind the tape back to 2008, when the first round of quantitative easing happened as part of the Fed's desperate moves to stop deflation. Deflation is perhaps the major concern of central banks, since it leads to a self-reinforcing cycle of economic collapse, as during the Great Depression. Disinflation, or falling but still positive inflation, poses similar though less severe problems. The first round of QE (consisting of basically ad-hoc purchases of bonds and assets up through mid-2010), in conjunction with the Recovery Act, bounced inflation back up into positive territory (though they fell far, far short of fully repairing the economy).

By that time in 2010, everyone was talking about the economy's "green shoots" and hordes of mindless austerian drones had seized power in Washington. But only a couple months after the Fed stopped its program, inflation was falling dangerously low, so they did another round of stimulus (this one called QE2), with $600 billion worth of purchases through mid-2011.

You can guess what happened next. Inflation kicked back up for a bit, but softened again all through 2012 after the program ended. That, plus the fact that job creation and growth both remained weak, led the Fed in September 2012 to try a timid paradigm shift. Instead of buying a particular quantity of assets, they would instead buy $40 billion per month on an open-ended basis, kinda-sorta committing to supporting the economy until recovery was achieved (dubbed QE3, or QE-infinity).

As with all these efforts, the Fed evinced a palpable reluctance to continue the program. Hard money paranoiacs, discredited by five years of failed predictions of skyrocketing inflation, switched gears and began complaining that stimulus would create financial instability. Thus, the Fed began "tapering" their asset purchases in December of last year, putting them on track to finish this month.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That brings us to today. The final round of QE barely seemed to affect inflation, which has been below the Fed's 2 percent target since early 2012. Here's the PCE deflator (the Fed's target measure of inflation):

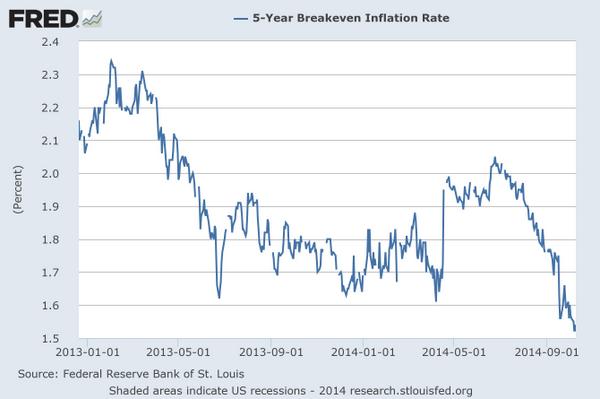

Worse, over the past few months, as the taper has progressed and inflationistas have begun eagerly discussing when the first actual rate hikes would happen, market expectations of future inflation have actually been crashing. Here are five-year inflation breakevens:

The weird thing about this most recent fall in expectations is that job growth has actually been pretty strong of late. Not nearly what most people would want, of course, but I would have thought it enough to keep inflation stable. Maybe it's that the crappy jobs being created in the recession just aren't putting enough purchasing power into the hands of the masses. Maybe it's disinflationary forces from Europe and Asia. Maybe it's something else.

Regardless, it seems fairly clear after three rounds of what I'll call "premature extractulation" that the economy is going to be chronically vulnerable to deflationary forces unless something fundamental changes. In theory, a gigantic new stimulus program from Congress might do the trick (ha-ha, as if). Realistically, for the foreseeable future the Fed is the only game in town.

That, in turn, ought to militate in favor of a real change in strategy at the Fed. There are very good reasons to believe that all-out stimulus just might jolt the economy out of its weak, disinflationary sandpit (or we could consider more fundamental reform to the Fed, allowing it to do more-effective stimulus). On the other hand, there are increasingly good reasons to believe that if they don't, we could be having this same dang conversation in 2024 over QE11.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Political cartoons for January 3

Political cartoons for January 3Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include citizen journalists, self-reflective AI, and Donald Trump's transparency

-

Into the Woods: a ‘hypnotic’ production

Into the Woods: a ‘hypnotic’ productionThe Week Recommends Jordan Fein’s revival of the much-loved Stephen Sondheim musical is ‘sharp, propulsive and often very funny’

-

‘Let 2026 be a year of reckoning’

‘Let 2026 be a year of reckoning’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook