Down to the wire: A brief history of close presidential elections

This year's contest might well fit into a storied tradition of Election Day nail-biters

When was the first close one?

The U.S. has had close — and bitterly disputed — elections since the earliest days of the union. In 1800, Federalist incumbent John Adams was beaten by two Republican candidates, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. But those two tied for the number of Electoral College votes, so it fell to Congress to decide whether the president should be Jefferson or Burr. With each of the 16 state delegations getting a single vote, Jefferson could not win a majority of states in 35 ballots cast over the course of an entire week. Finally, in the 36th round, a lone Federalist from Delaware, James Bayard, changed his vote, assuring Jefferson's victory. Jefferson was so worried about the divisive nature of his election that he had armed soldiers escort him to his inauguration. To prevent such chaos in future elections, the states four years later ratified the 12th Amendment of the Constitution, which separated the votes for president and vice president and set out new procedures for the Electoral College.

Did the 12th Amendment prevent controversy?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It actually complicated the election of 1824, when Andrew Jackson won a plurality of popular and Electoral College votes, but was denied the presidency for failing to win a majority in the college. Under the 12th Amendment, the decision then fell to the House of Representatives, which elected runner-up John Quincy Adams at the direction of Henry Clay, the speaker of the House. Adams promptly appointed Clay secretary of state. Jackson furiously denounced a "corrupt bargain," and immediately began campaigning for the 1828 election — a race he would win in a landslide. Nearly a half century later, in 1876, the country was shaken by what remains the most divisive presidential election in our history.

What happened in 1876?

Samuel J. Tilden, a Democrat from New York, easily won the popular vote over Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes. But ballot-stuffing and bribery in three Southern states — Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina — made it impossible to arrive at a definitive Electoral College result. Republicans in Louisiana were said to have solicited $1 million to declare Tilden the winner. With both parties declaring victory, fears were rife that the split would lead to another civil war. Congress established an electoral commission in January 1877, which eventually ruled Hayes the winner of Florida, putting him over the top. Hayes's presidency was thereafter plagued by the scandal — Democrats branded him "Rutherfraud B. Hayes" — but Tilden took his loss graciously. "I shall receive from posterity the credit of having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people," he said, "without any of the cares and responsibilities of the office." It would not be long, however, before an election again hinged on a single state.

Which state was that?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

California, in 1916. Woodrow Wilson ran for re-election against Republican Charles Evans Hughes, a stoic New York lawyer nicknamed "the Bearded Iceberg" by Teddy Roosevelt. Early returns suggested that the Republicans had taken California, thereby guaranteeing Hughes's victory, and he went to bed on election night believing himself the winner. Legend has it that a reporter tried to contact him the following morning to get his reaction to Wilson's victory in California, only to be told by a butler that "the president is asleep." "Well," said the reporter, "when he wakes up, tell him he isn't the president." Wilson won California by a 0.3 percent margin to become the first Democratic president since Andrew Jackson to be re-elected.

Wasn't the 1960 election also disputed?

The Nixon-Kennedy clash is remembered as one of the tightest races of the 20th century. Many Republicans believe Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley effectively stole the election for Kennedy by ballot-stuffing, vote theft, and other dirty tricks; investigations later confirmed that his ward bosses had bought votes from bums with whisky shots. Kennedy won Illinois, which had 27 electoral votes, by fewer than 9,000 votes, but his overall margin of victory in the Electoral College — 303 to 219 — was larger than most people remember, so he would have won without Illinois. The closest election in recent history came in 2000, when Al Gore won the popular vote by more than 500,000 votes, but lost in the Electoral College when the U.S. Supreme Court stopped a recount in Florida.

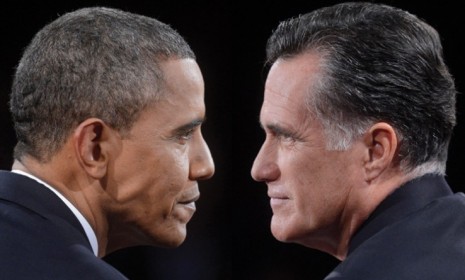

Could 2012 be a rerun of 2000?

Most analysts consider the 2000 election a once-in-a-lifetime confluence of unlikely events, but just as that race came down to Florida, this one could hinge on Ohio. Its 18 electoral votes are expected to be decisive, and if the race there is as close as some projections say, another waiting game could be ahead. More than 800,000 Ohio voters requested absentee ballots that still haven't been turned in. Any of those voters who opt to go to a polling station after all will be required to cast provisional ballots, and state law says those votes cannot be tallied until Nov. 17. "We could easily see a situation," said Ohio State law professor Ed Foley, "in which the nation has to wait for Ohio."

The New York Times' Republican era

Some conservatives see The New York Times as the worst of the "liberal media" weighting the scales for Democrats. But the Gray Lady once actively helped the Republicans swing a close election. In 1876, a Democratic Party official got in touch with the Times on election night. Though Rutherford Hayes had privately conceded and Sam Tilden's victory seemed guaranteed, the official nervously sought confirmation that Tilden really had enough electoral votes. The Times' managing editor, John Reid, who was a Republican, figured that if the Democrats weren't sure that Tilden had won, the GOP still had a chance. Reid quickly wired Republican party bosses in the undeclared states of Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina. "If you can hold your state, Hayes will win," he wrote. "Can you do it?" The GOP did. Hayes withdrew his concession and ended up in the White House.

-

Political cartoons for January 3

Political cartoons for January 3Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include citizen journalists, self-reflective AI, and Donald Trump's transparency

-

Into the Woods: a ‘hypnotic’ production

Into the Woods: a ‘hypnotic’ productionThe Week Recommends Jordan Fein’s revival of the much-loved Stephen Sondheim musical is ‘sharp, propulsive and often very funny’

-

‘Let 2026 be a year of reckoning’

‘Let 2026 be a year of reckoning’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook