For Republicans, might makes right is back in fashion

Eight years later, we're back where we started

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Six years into his presidency, President Obama’s foreign policy doctrine can best be summed up in an aphorism: haste makes waste.

"When we make rash decisions, reacting to the headlines instead of using our heads; when the first response to a challenge is to send in our military — then we risk getting drawn into unnecessary conflicts, and neglect the broader strategy we need for a safer, more prosperous world," Obama said in his State of the Union on Tuesday night. "That’s what our enemies want us to do." This is slightly better than "don't do stupid shit."

Though the president spent a quarter of his speech on foreign policy and national security, at the Republican National Committee winter meeting aboard a decommissioned aircraft carrier in San Diego this weekend,"Not only was foreign policy front and center of every address, but the contenders were all convening around a hawkish, almost neoconservative position similar to where Mitt Romney was when he ran in 2012," noted Bloomberg View's Josh Rogin. Obama's foreign policy "was based on the premise that if we were friendly enough to other people and if we smile broadly enough and press the reset button, then peace is going to break out around the world," Romney said.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

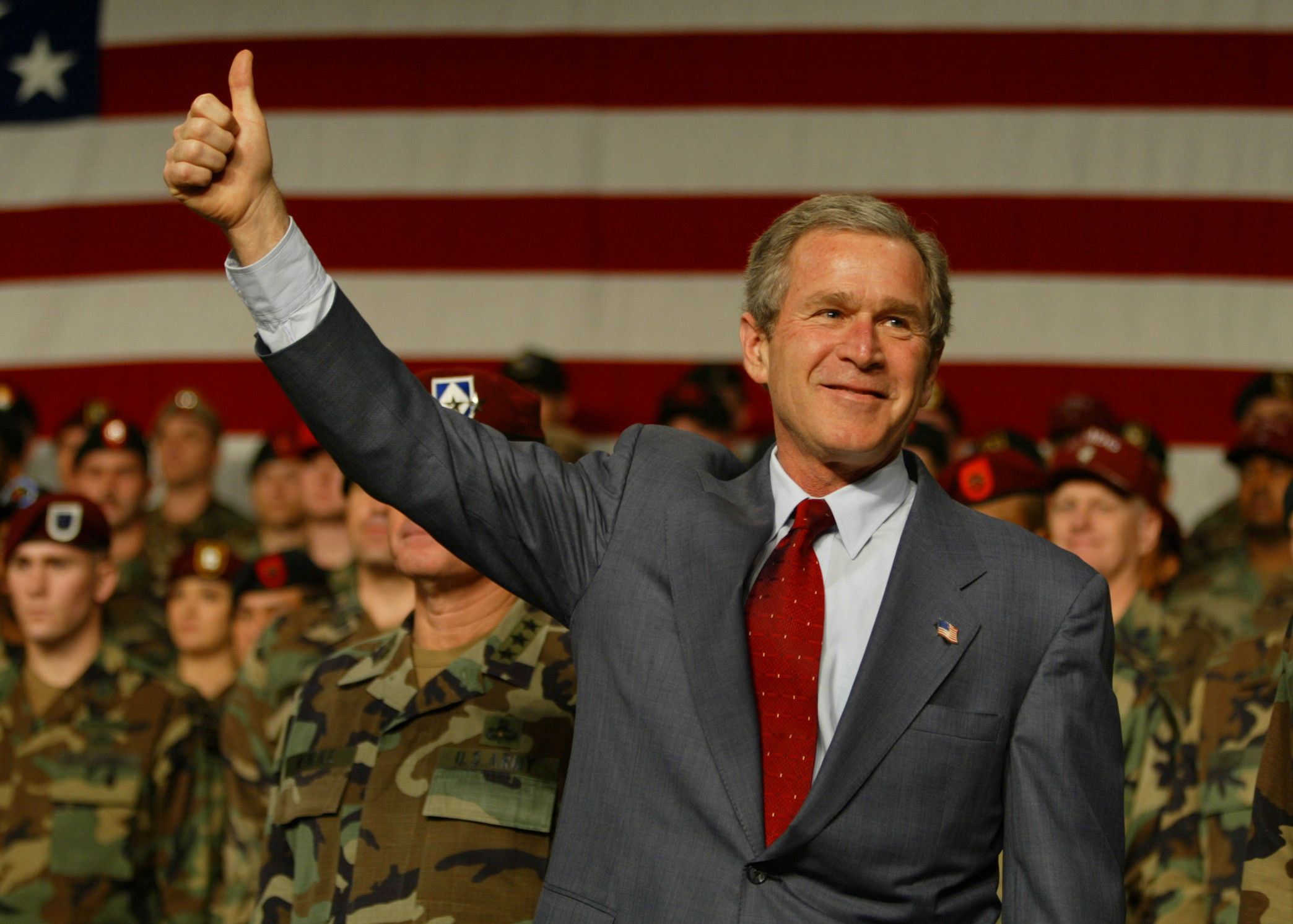

The Republican position is not just similar to what Mitt Romney found himself saying in 2012, but also similar to the argument George W. Bush found himself making in 2002, when he was trying to explain how 9/11 could have happened, and also where conservatives found themselves in the twilight of the 1970s, when detente seemed to shift the axis of the world eastward.

For a while, it seemed as though Democrats had finally found the fix for their decades-long flaccidity on national security. After 9/11, to dismantle al Qaeda, Americans supported an aggressive confrontational interventionism. But when President Bush drew upon this support to make war with Iraq, and the result was chaos, and not the discovery of WMDs, the Might Makes Right faction in Republican politics took a blow. Democrats didn't have any brilliant ideas, but by 2006 their support for a more modest internationalism seemed the better alternative.

Eight years later, though, and we're back where we started. External events, and surprises, surely push the pendulum of public opinion in one direction or another, but it inevitably swings back to the center of gravity. That we can best describe it as a pendulum to begin with shows how stable these views are.

Because the public perceives what Brookings' Bill Gallston calls "an arc of crises" from Europe to North Africa and throughout the Middle East, with the U.S. seeming unable to influence their disposition, Republicans sense opportunity. Since the early party of the Vietnam War, Americans have responded well to a particular set of throwdowns when they perceive danger.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The argument is basically a playground challenge to American manliness: do you want to be strong? Or do you want to be weak? Are you really (to paraphrase Fritz Kraemer) "so weak of will that you accept no risks and want to intervene with real force only when no sacrifices can be required?" Politicians who project strength at all cost tend to win these contests, even though Americans are operationally much more skeptical of actually intervening then they appear to be. Bill Clinton calls this the tendency to embrace "strong and wrong" over "smart and right." Surprises and shocks can move the needle a bit, but this preference is pretty stable.

Before 9/11, Democrats and Republicans might have disagreed about foreign policy and the conduct of the Cold War, but the sources of contention were not generally ideological as much as they were generational and practical. In 2002 and 2004, after the rally effect died down, the Republicans deliberately linked their political opponents to the ideological misjudgments of their enemies.

More perniciously, and ingeniously, they cast aspersions on motive. They refought the Vietnam War and openly questioned the patriotism of a veteran who served in it. That they could do this and get away with it might well give media critics something to write theses about for decades, but the simplest explanantion is that the Republicans did it because the party leadership figured out what their base believed and stuck to it like leeches stick to blood. The GOP remains fairly ideologically homogenous on national security. This is why libertarians who align with the GOP, atlhough able to get more attention (thanks, internet!), are not at all a real force.

The other party's base — stalwart Democrats who are reasonably well informed about issues — is hard to pin down. The party has never really adopted a genuine foreign policy consensus. A large number of liberals (anywhere from pluralities to majorites in polls) do not support President Obama's counter-terrorism strategy when it's described to them. It is confused by his decisions to leave troops in Afghanistan and to fight against ISIS in Iraq. It is skeptical of NSA surveillance. The Democratic base has a habit of finding plausibly anti-war candidates early on and then opening up a pathway for them to win the nomination. This worked with Obama initially; it failed with Howard Dean.

If the economy remains strong and the Affordable Care Act becomes more popular, the best argument for change is that Obama, with Hillary Clinton's essential help, squandered American power by trusting too much in feckless international institutions and too little in America's innate superiority. The presidential candidates who focused on foreign policy at the RNC Winter Meeting knew what their audience wanted to hear.

These political veterans have one goal: find the candidate who has the best chance of beating Hillary Clinton in a general election.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

‘Those rights don’t exist to protect criminals’

‘Those rights don’t exist to protect criminals’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Key Bangladesh election returns old guard to power

Key Bangladesh election returns old guard to powerSpeed Read The Bangladesh Nationalist Party claimed a decisive victory

-

Judge blocks Hegseth from punishing Kelly over video

Judge blocks Hegseth from punishing Kelly over videoSpeed Read Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth pushed for the senator to be demoted over a video in which he reminds military officials they should refuse illegal orders

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred