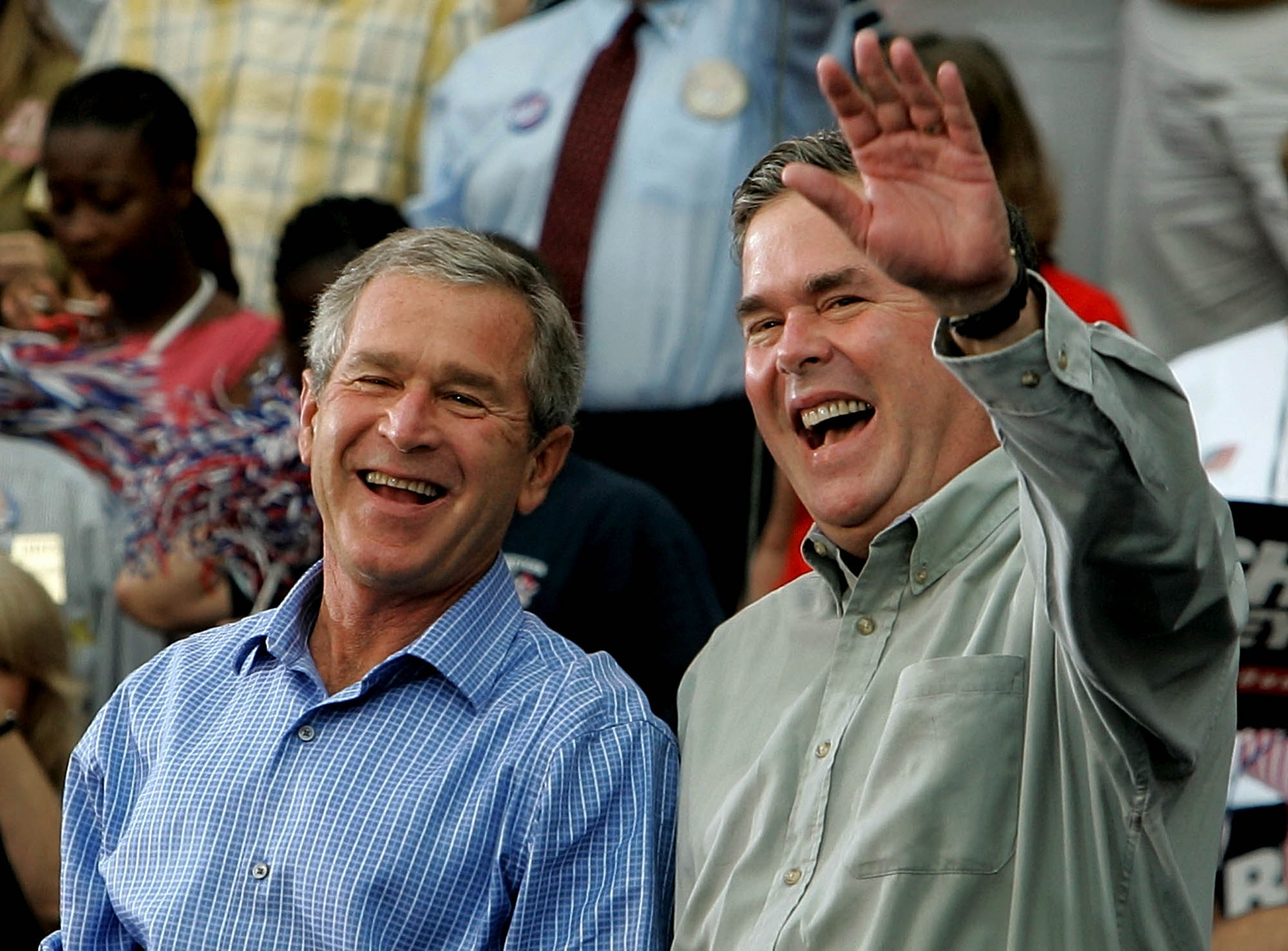

How Jeb Bush is tweaking his brother's brand of 'compassionate conservatism'

Jeb's 'inclusive conservatism' is a nod to how times have changed

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Remember when George W. Bush sold himself as a "compassionate conservative"? Of course you do. Now, his brother Jeb is using a similar formulation, describing himself as an "inclusive conservative." The difference may seem trivial at first, but the Bushes are no fools when it comes to winning elections. And this difference tells us something about the changing perception of the parties, as well as the changing priorities of left and right.

In both cases, the descriptors seek to soften or modify "conservative." Back in 1999 and 2000, some felt that "compassionate conservative" was kind of backhanded, implying that plain old conservatives aren't compassionate. But the slight to the right was necessary. Until a functioning electoral majority begins referring to itself in Mitt Romney's preferred formulation of "severely conservative," a national candidate for the center-right party will always need to at least claim that he is reaching out to the center and center-left.

But the similarities between Jeb and George's brands end there. "Compassionate" implied that George would be solicitous of the economic interests of the working class and the poor. He even said that as president he would be the leading lobbyist on behalf of the poor. It was a concession that the chief problem for the Republican Party was that it was seen as the party of big business and the wealthy, not the little guy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This perception still holds. A recent Pew survey found that 60 percent of respondents said the Democratic Party "cares about the middle class." Forty-three percent of respondents said the same of Republicans, a 17-point gap.

But the same Pew survey found that 59 percent of respondents said that Democrats are "tolerant and open to all groups of people," and only 35 percent said the same of Republicans, a 29-point gap.

"Inclusive" is a word that says much less about economics. It's a cultural word, the kind used in college campus orientation literature. It is also corporate-speak, usually swiftly preceded or followed by phrases like "commitment to diversity." Intentional or not, Jeb's tweak of a re-brand gets at this larger partisan gap.

This is the latest sign that culture war issues continue to move to the front of our politics, while economic issues take a back seat. Fifteen years ago, the Republican problem was that it seemed to have nothing tangible to offer the poor, blacks, or others on the margin of society. For Jeb, the problem with conservative conservatism is that it is exclusive. Conservatism is for the married, white, Christian, suburban, and exurban.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Instead of holding out "compassion" through faith-based initiatives, or the promise of an ownership society, Jeb's promise of "inclusion" is much more amorphous. It's not a promise to be more solicitous of the interests of LGBT voters, single women, or immigrants than the Democrats. It's more of a pledge not to antagonize them culturally — or at least not as much.

The branding may not matter if Jeb gets into office. George encouraged some aid to Africa, but his presidency was hardly defined by "compassionate conservatism." His faith-based initiatives eliminated some anti-religious discrimination in federal funding, but it did not come close to transforming the provision of social welfare. Nor did it evolve into a kind of federally funded theocracy, as critics feared. The ownership society blew up with the subprime crisis, hurting the most marginal homeowners.

But the branding is a good measure of where American political culture is today. Hillary Clinton is not exactly a candidate that screams, "For the little guy." Not with the almost daily news of her mid-six-figure buck-raking speeches, and seven-figure donations to the Clinton Foundation from foreign governments.

The truth is that in 2016, there is not going to be a candidate looking to turn the federal government into the best friend of the poor. Not Hillary Clinton, not Jeb Bush, certainly. So it probably makes sense for Jeb to try to head off the inevitable round of culture war–baiting that is coming his way.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.