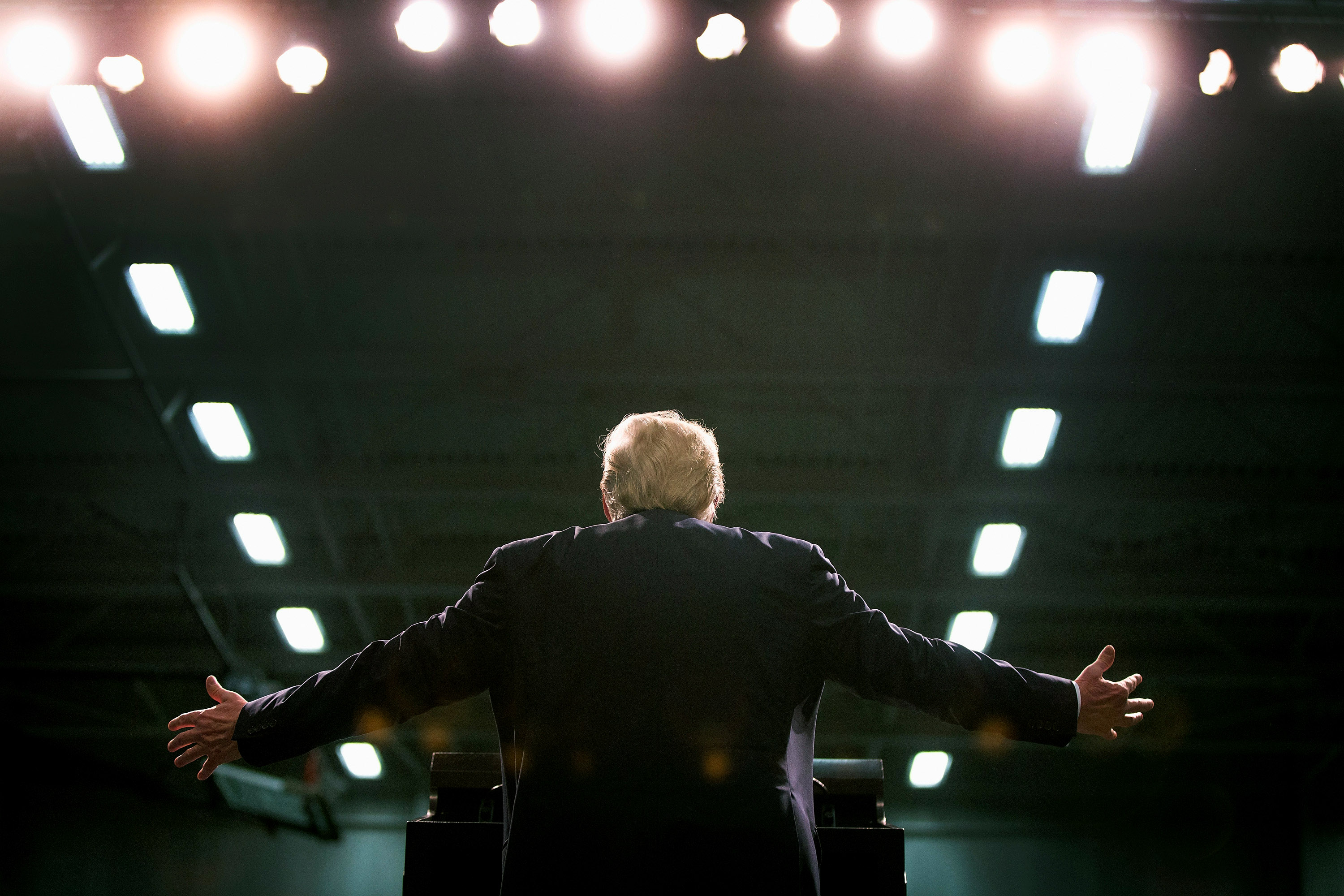

How the Merrick Garland nomination explains the rise of Donald Trump

When you treat governing like a joke, you wind up picking a joke of a presidential candidate

When Antonin Scalia died and Republicans quickly announced that they would not just oppose whoever Barack Obama nominated to replace him on the Supreme Court but refuse to grant that nominee so much as a hearing, let alone a vote, no one who has watched American politics closely in recent years could have been surprised. Appalled, disgusted, outraged? Sure. But surprised? No.

The wise constitutional scholars in the GOP were quick to note that there's nothing in our government's foundational document that prevents them from doing what they're doing. The Constitution says the president "shall appoint" members of the Supreme Court, but it doesn't require that the Senate confirm his choices, nor does it lay down the particular procedures they need to follow. And if they decide that they won't even go through the motions in an election year, no one can stop them. So there.

And that is the breakdown of our political system in action. The problem is not the Republicans' growing ideological extremism, troubling though that may be. The problem is that they decided some time ago that there are rules and there are norms, and while rules need to be followed, norms can be torn down whenever they find that doing so advances their momentary political goals.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That may not sound like a big deal, or anything more than ordinary hardball politics. But the Republican willingness — indeed, eagerness — to abandon traditional norms of governing has crippled our political system.

While others might locate a different starting point, I'd argue that the seminal moment of this trend was the "Brooks Brothers riot" that occurred on November 19, 2000, during the counting of the disputed votes in Florida. Worried that election officials recounting votes in Miami-Dade county might produce a result favorable to Al Gore, Republicans sent congressional staffers posing as ordinary Floridians to the offices where the counting was taking place. They proceeded to shout, pound on doors, and generally intimidate the election officials, who eventually became so frightened for their safety that they stopped the counting.

That was just one particularly vivid incident in a remarkable story, in which the election came down to a state governed by the Republican candidate's brother, where the Republican candidate's state co-chair was also the state's chief election official, where the two of them had engineered a "purge" of voter rolls that had disenfranchised thousands of legitimate voters, and where the counting was eventually stopped by five Republican members of the Supreme Court, in what was one of the most absurd and shameful decisions in its history.

And what lesson did Republicans take from all that? We won.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As the ensuing years rolled along, they came again and again to points where their goals were hampered not by a rule, but by a norm. There's a Democratic president who for a time enjoyed the support of a Democratic Congress — so how about if we just filibuster everything? Sure, in the past filibusters had only been used in extraordinary circumstances. But there's no rule saying you can't filibuster everything, so they did it. You can hold up presidential nominations indefinitely, you can shut down the government, you can threaten to default on the debt — there's no law against any of it.

You may hear the word "norms" and think about things like courtesy or shopworn habits, but the truth is that there are many norms whose function is to permit government to operate in something like an efficient fashion. For instance, the norm by which the Federal Election Commission used to operate is that while the Commission's three Democratic and three Republican commissioners will have different views about election law, all will accept the basic premise that whatever they think the laws ought to be, the laws currently in place should be enforced. But the Republican commissioners have abandoned that norm, and as a result our election laws are simply not being enforced; at this point it's basically an honor system.

That's not to mention the fact that the people who have come to dominate the Republican caucuses in the House and Senate arrived in Washington not to make laws, but to tear the institutions of government down. So it's quite alright with them if nothing in Washington works — after all, that only validates their argument to voters that government can't do anything right, and what we should do is continue to undermine it and strip away its protections wherever we can.

The GOP is divided between those people — variously called the Tea Party or the base or the insurgents — and the rest of the party, who are terrified of them and feel the need to continually prove their anti-government bona fides and ideological purity. So the entire party embraces not just ideological radicalism, but a procedural radicalism as well.

Then you can combine that with the positively venomous loathing all Republicans seem to share for Barack Obama. It was only a norm that said you don't shout "You lie!" at the president during a speech to Congress, or that you don't demand to see his birth certificate, or that you don't accuse him of hating America just because you have political differences. Put it all together, and of course Republicans would refuse to allow him to name a new Supreme Court justice.

Where does this all lead? To Donald Trump.

When your party proves again and again that it treats governing like a joke, you wind up picking a joke of a candidate to be your nominee for president. You choose someone who doesn't know the first thing about how government works, and couldn't care less. You push your voters to the least serious person, the one who "tells it like it is" — in other words, the one with the most contempt not just for the norms of politics but for the norms of civilized human behavior. That's what Republicans have ended up with. And they pretend that they can't understand how such a thing could have happened.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

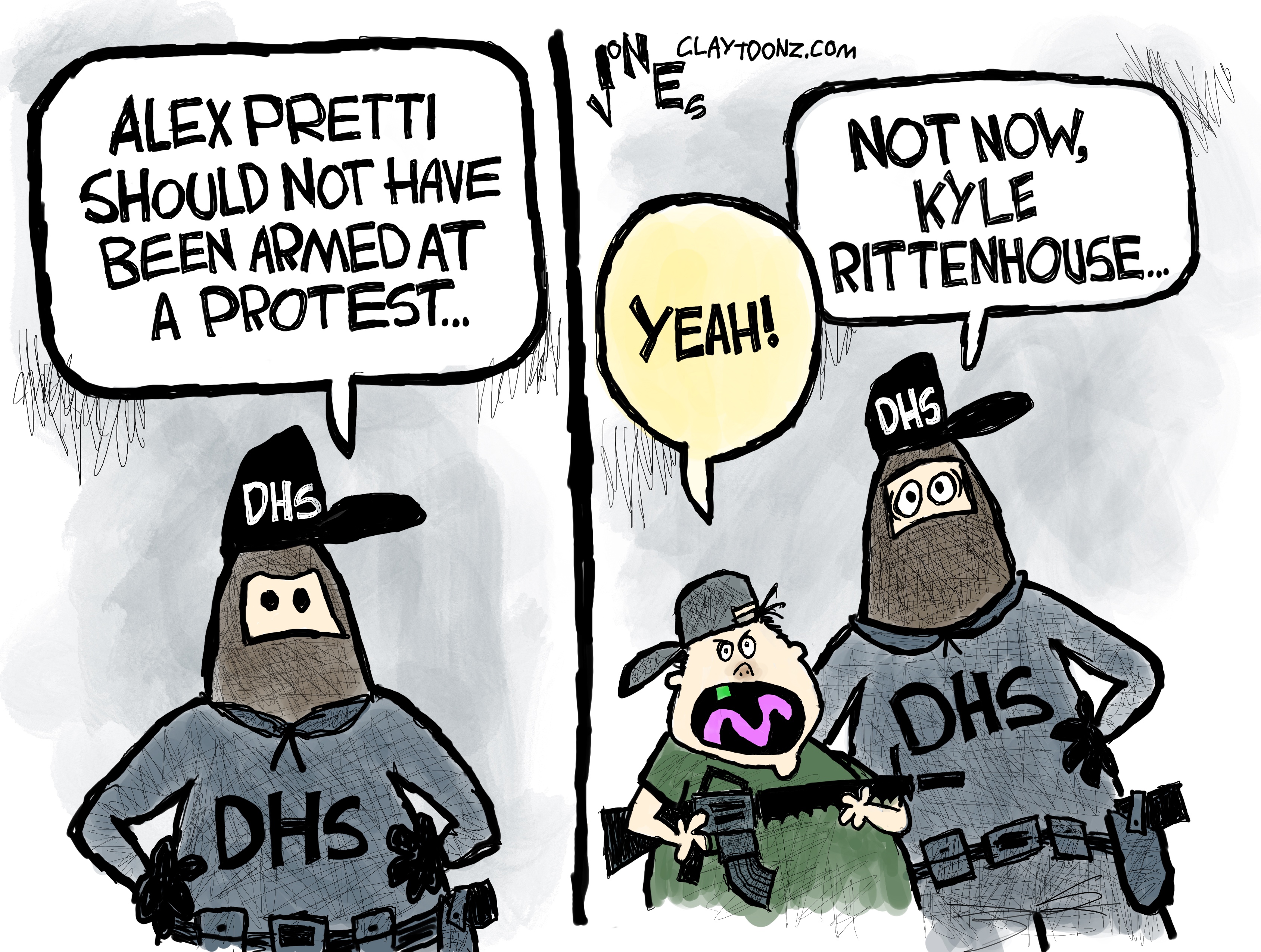

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred