Hillary Clinton loves to trumpet Bill's budget surplus. She shouldn't.

The case against balancing the budget

One thing Hillary Clinton has been able to bank on this election is the association between the Clinton name and economic boom times.

The late 1990s during former President Bill Clinton's administration were a remarkable period: The unemployment rate hit just 4 percent, wages grew at 4 percent, and — most famously — the federal budget actually ran a surplus from 1997 to 2001, peaking at $236 billion in 2000. "We had a balanced budget and a surplus when my husband left the White House," Clinton said in July, lamenting the Bush administration's turn back to deficits in the 2000s. "I would hope, with sensible economic policy, we could get back moving toward balance."

Not surprisingly, Clinton hinted last week that the man who oversaw that surplus will be given some major role revitalizing the economy, "because, you know, he knows how to do it."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The standard response to this is that presidents' impacts on the economy are limited and hard to isolate. Which is true. But there's also a deeper critique to be made: Namely, that Clinton's budget surplus wasn't everything it's cracked up to be. In fact, it might have hurt the economy pretty badly.

The key to understanding why rests with an underappreciated economic tool called "sectoral balances" analysis. As Eric Tymoigne — an economics professor as Lewis and Clark College in Portland — explained to The Week, it's incredibly useful for understanding macro-economic trends. Let's walk through how it works.

A sectoral balances analysis starts with the recognition that the U.S. economy, like any national economy, is roughly comprised of three sectors. There's the government sector: the federal government, the Federal Reserve, and the state and local governments. There's the private domestic sector: individuals, households, businesses, the banks, all the major industries, etc. And then there's the foreign sector: i.e. the rest of the world, or every entity outside the U.S. national border that we trade with.

Each of these three sectors are in a state of surplus or deficit at any given moment. The government is either taxing more than it spends (surplus) or spending more than it taxes (deficit). Households and businesses in the private domestic sector are either saving more than they're spending (surplus) or vice versa (deficit). And the rest of the world is either exporting more to America than it imports (surplus), or importing from the U.S. more than it exports (deficit). (Perhaps confusingly, the foreign sector balance is the inverse of the U.S. trade balance; i.e. a surplus in the foreign sector actually means a U.S. trade deficit.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And because of the way we calculate gross domestic product (GDP), the sum of the deficits or surpluses of these three sectors will always be zero. So if the domestic private sector is running a surplus of 4 percent of GDP, for instance, then the government and foreign sectors might each run a deficit of 2 percent.

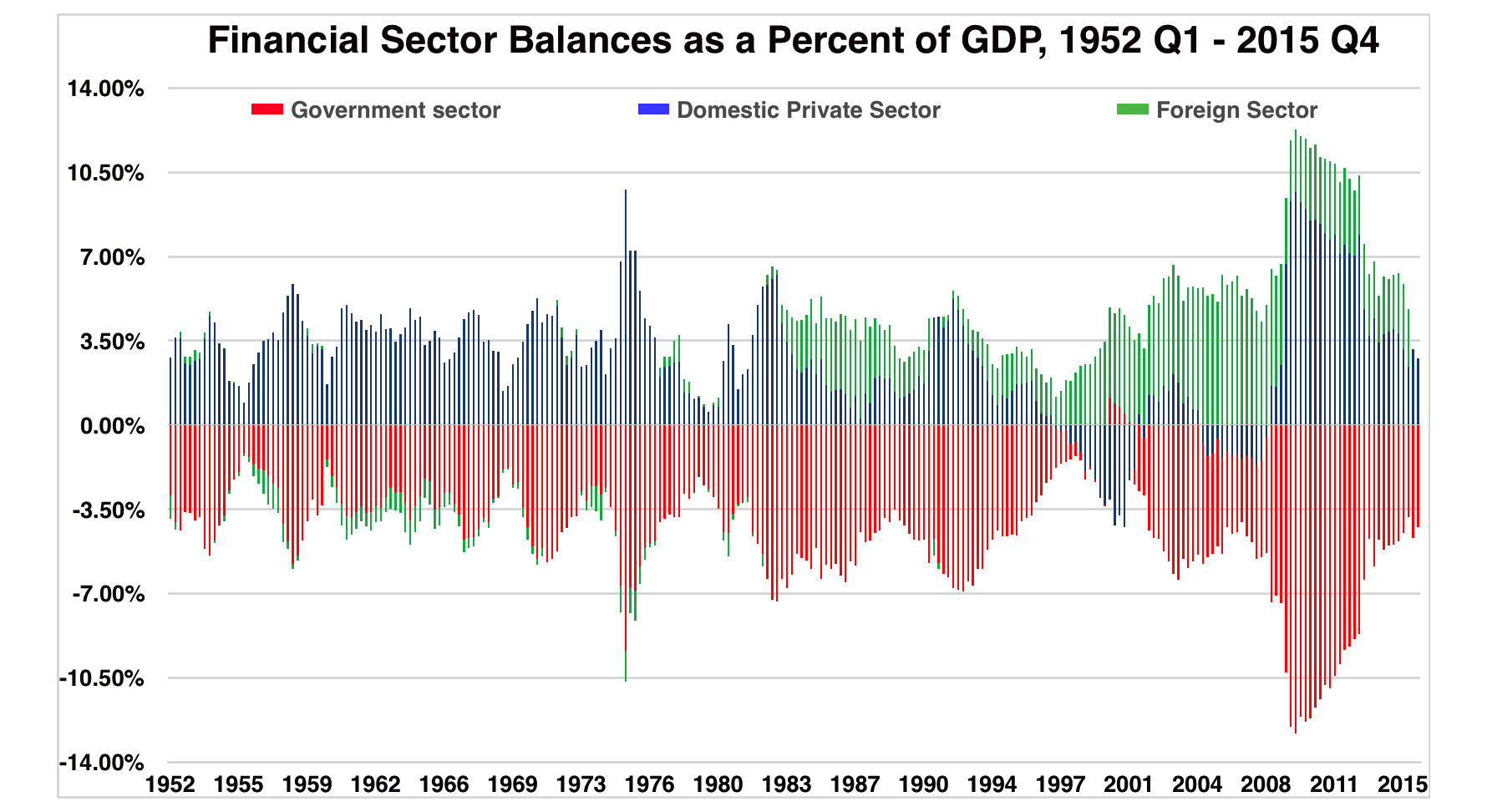

You can see how this works in the real world in the graph below, which was provided by Scott Fullwiler, an economics professor at Wartburg College. The government sector is in red, the private domestic sector is in blue, and the foreign sector is in green:

As you can see, the government sector has almost always been in deficit since the mid-20th century while the private sector has almost always been in surplus. But what do you notice about the late 1990s? Something weird happened: The private domestic sector (the blue bars) went into deficit for the first time since 1952. Then it did it again in the second half of the 2000s. There's no way for the spending of private households and businesses to collectively outpace saving unless its being driven by unsustainable debt. So what we're seeing here is the stock bubble of the late '90s, which burst in 2001, and the out-of-control mortgages and household debt of the mid-to-late '00s, which culminated in the 2008 financial crisis.

The graph also illustrates why the persistent foreign sector surplus (which, remember, means a U.S. trade deficit) that opened up in the 1990s is such a problem: It must be balanced by either a government sector deficit or a private domestic sector deficit. And though the federal government isn't the entirety of the government sector, it's still a major part. So while President Clinton and the GOP Congress were building a federal surplus in the 1990s, they were also pushing the private sector into debt.

"If the government is able to reach a surplus, that means it's draining funds out of the economy," Tymogine explained. "It's taxing away more money from the other sectors than it's injecting."

The lesson here is that it's much more sustainable for the government sector to be in deficit, because it contains the federal government. And unlike any entity in the other two sectors, the federal government isn't cash-constrained: it controls the supply of U.S. dollars, so in a pinch it can always print more to pay off whatever debt obligations it has stocked up. This carries inflationary risk, but it also means it's basically impossible for the federal government to suffer a debt crisis. And you can see that in the chart: The government sector has been in deficit basically forever, and we've yet to have a debt crisis.

Meanwhile, the private domestic sector is cash-constrained, and can suffer a debt crisis quite easily. It only went into deficit a little bit for short periods in the late 1990s and 2000s, and that was enough to blow up the entire economy.

So next time you hear someone praising the Clinton economy and federal surpluses, remember sectoral balances. And think twice.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Why don’t humans hibernate?

Why don’t humans hibernate?The Explainer The prospect of deep space travel is reigniting interest in the possibility of human hibernation

-

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?Today’s Big Question ‘Mildness’ of EU pushback against Trump provocation ‘illustrates the bind Europe finds itself in’

-

The rise of runcations

The rise of runcationsThe Week Recommends Lace up your running shoes and hit the trails on your next holiday

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook