Hungary's version of 'the Miracle on Ice' is called 'Blood in the Water'

This water polo match between Hungary and the Soviet Union had real stakes — and real blood

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The myth of the modern Olympiad is that the quadrennial games are a time of universal brotherhood where petty differences between nations are put aside in the spirit of fair play. But it is only that: a myth.

The 1936 Berlin Games were the Nazis' coming-out party as players on the international stage. The Summer Games in 1980 and 1984 were boycotted by the United States and the Soviet Union, respectively, in a Cold War skirmish. And there was, of course, the "Miracle on Ice," where a bunch of college kids from the United States upset the dominant Soviets in the winter of 1980. But that is all Disney movie material compared to the danger and intrigue of "Blood in the Water."

Taking place almost 60 years ago at the 1956 Melbourne Summer Games, this infamous water polo match between Hungary and the Soviet Union is the true apex of the Olympics-as-war metaphor.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Like nearly all of Central and Eastern Europe post-World War II, Hungary had fallen under the yoke of one of the 20th century's greatest monsters, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, who when he wasn't murdering millions of his own people and sending millions more to the gulag, was setting up puppet communist governments to form the Iron Curtain.

When Stalin died in 1953, his successor Nikita Khrushchev denounced the cult of personality Stalin created, and also partially exposed his crimes against humanity (and the Soviet people, in particular). Khrushchev essentially promised a kinder, gentler communist empire, but that didn't mean he intended to allow any autonomy from his satellite states.

Then-Hungarian Premier Imre Nagy took the change in Soviet leadership as an opportunity to push for reforms. Specifically, Nagy wanted what his people wanted: independence from the Soviet Union. Naturally, that didn't sit well with Khrushchev, who had Nagy removed from office in 1955.

But in October 1956, over 200,000 Hungarians peacefully took to the streets demanding freedom and independence. When the state police began to fire on the protesters, a revolution began. Nagy was re-instated as prime minister, while Soviet tanks guarded government buildings. Sporadic violence continued for more than a week, but for a moment, it appeared the Soviets would back down, and Hungary would realize its intention to leave the Warsaw Pact and pursue its future on its own terms.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It was during this uneasy period of calm that part of the Hungarian Olympic team left the country on a three-week nautical journey to Melbourne aboard a Soviet ship (the rest of the national team would later fly out of Prague).

When the team arrived in Australia, they learned what had become of their revolution: It had been brutally crushed by the Soviets. Over 3,000 of their countrymen were dead. A few days later, Nagy would be arrested, and later tried in secret, then executed for treason.

The Hungarian water polo program has been a powerhouse of international competition for nearly a hundred years, and in 1956 was preparing to defend a gold medal won in the 1952 Helsinki Games. During the brief and ill-fated revolution, ordinary Hungarians had taken to flying the pre-communist tricolor national flag, or simply cutting a hole in the center of the current flag and removing the crest bearing the communist star which had been added post-1949. Hungary's newly-installed Soviet puppet regime ordered its athletes to not carry the national flag at the game, but the Hungarian Olympians — nearly 10,000 miles from their broken homeland — waved the tricolor in defiance of their own government.

It was in this atmosphere that the Hungarian water polo team saw the "CCCP" insignias on the uniforms of their Soviet opponents — the same seal which adorned the Soviet tanks that had crushed their aspirations of self-determination — and they didn't lack for any more inspiration.

After beating the U.S., Germany, and Italy in round-robin play, the Hungarians got in the pool with the Soviets in the semifinals. It just so happens that Melbourne was home to a large Hungarian community, which packed the stands and ravenously rooted against the Soviets every bit as much as they rooted for their ancestral countrymen.

One of Team Hungary's standout players, Ervin Zador, told the BBC many years later that despite the rage born of profound anguish he and his teammates felt over the lost revolution, they weren't going to get themselves disqualified by engaging in wanton violence against the Soviet athletes. However, the Hungarians fully intended to bait the Soviets into losing their tempers, which they did, resulting in numerous penalties and a generally undisciplined performance that the Hungarians in turn capitalized upon.

The Hungarians called the Soviets "dirty bastards," and the Soviets countered that they were traitors. Flailing submarine sucker-punches were thrown, kicks were deployed, but Hungary's strategy worked. The flustered Soviets faced a 4-0 deficit late in the match.

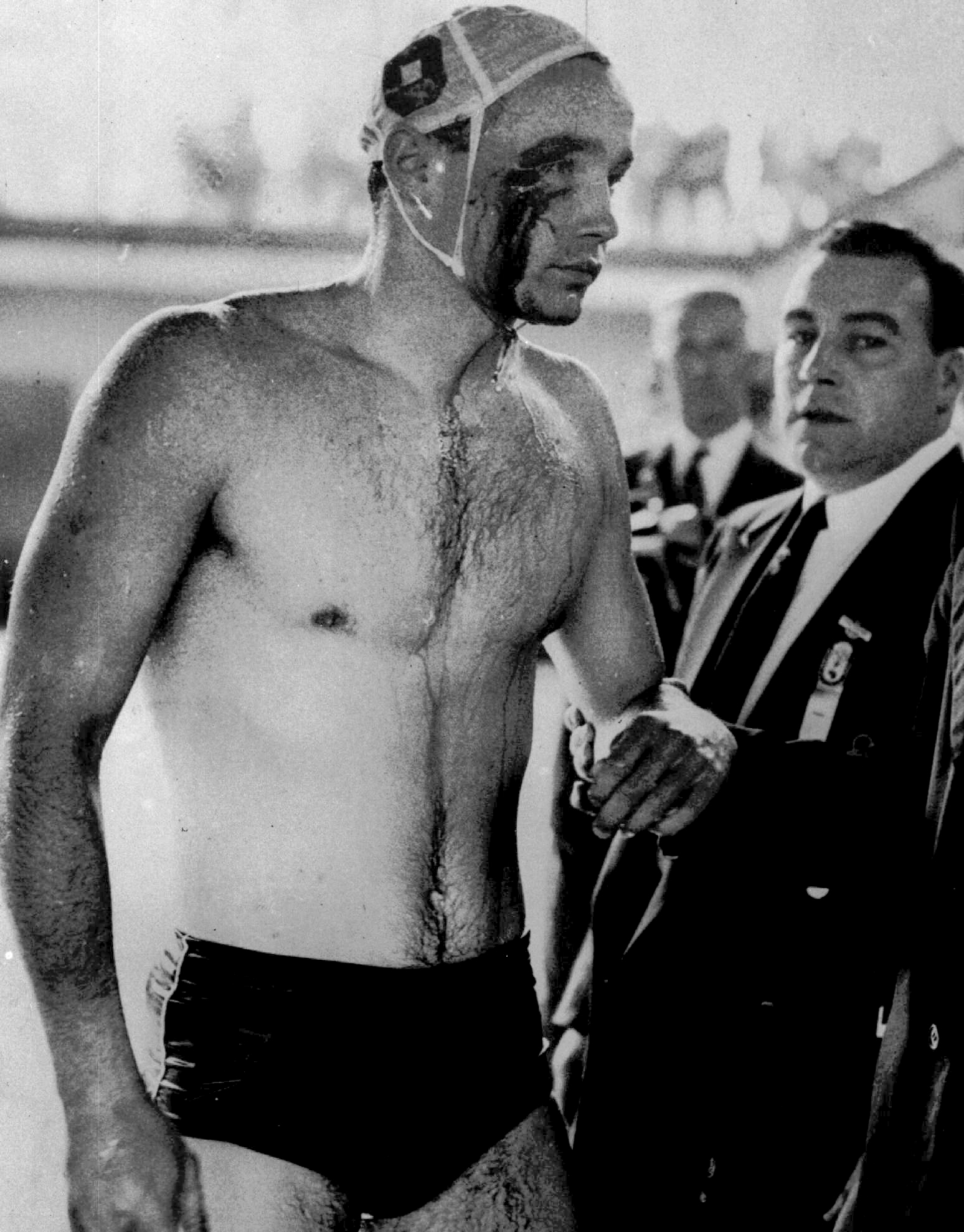

With just two minutes to go, star Soviet player Valentin Prokopov was goaded by one too many Slavic "your mama" jokes from Zador and rose from the water, viciously punching his Hungarian rival in the face.

Blood gushed from the side of Zador's right eye, making the Hungarian look "like he just stepped out of a slaughterhouse," according to one of his teammates. Many in the incensed crowd of spectators breached the barriers, hurling various projectiles at the Russian team, but the well-prepared-for-trouble Melbourne police held them off. Zador was taken for medical attention, and the match was halted, resulting in a victory for Hungary.

When photos of a bloody Zador were circulated around the world, the "Blood in the Water" match became instant legend. But to this day, the Hungarian Olympians insist the Russian team were not the "barbarians" they were made out to be in the press, but merely hard-nosed competitors who lost their cool in a spirited contest.

In the Quentin Tarantino-executive produced 2006 documentary Freedom's Fury, one Hungarian player maintains that while the Soviet government and military were absolutely exhibiting barbaric behavior, the Soviet players had not. Zador would go so far as to say the Soviet players "were as much victims of those circumstances as we were."

Hungary would go on to win the gold medal match, 2-1 over Yugoslavia, though Zador's injuries would keep him from participating. At the Games' conclusion, half of the water polo team refused to return to Hungary — where they would have received a hero's welcome — and instead became political refugees. Zador ended up in California, where he lived the rest of his life, raising a family and becoming a swimming coach of distinction — even training future Olympic gold medalist Marc Spitz.

The Soviets would lead the 1956 Games with 37 gold medals (and 98 medals overall), but Time magazine would name the "Hungarian Freedom Fighter " as its 1956 Man of the Year.

In the quarter-century since the decisive end of Soviet communism, the "Miracle on Ice" and Rocky Balboa's absurd (even by 1980s Reagan-era jingoistic Hollywood standards) pugilistic duel with steroid-enhanced Soviet boxer Ivan Drago in Rocky IV are probably the most enduring images of Cold War geopolitics playing itself out in sport. But the 1956 "Blood in the Water" match was true high-stakes drama, where the field of play briefly masqueraded as a battlefield.

Anthony L. Fisher is a journalist and filmmaker in New York with work also appearing at Vox, The Daily Beast, Reason, New York Daily News, Huffington Post, Newsweek, CNN, Fox News Channel, Sundance Channel, and Comedy Central. He also wrote and directed the feature film Sidewalk Traffic, available on major VOD platforms.