The troubling rise of American pessimism

Donald Trump's success at winning the Republican nomination is a powerful sign that the pessimism of the late 1970s has returned, albeit in darker, angrier form

America is supposed to be a nation of optimists.

Founded and then continually joined by people who made great efforts and took enormous risks to come here from other places, the country's economic and geopolitical rise has been fueled from the start by great individual and collective hopes and ambitions. We are a nation of strivers and believers.

There are, of course, exceptions. During the mid- to late-1970s, for example, the country briefly fell into a funk. Reeling from the collapse of liberal idealism, rising rates of crime, defeat in the Vietnam War, and the resignation of a president brought down by scandal, Americans began to succumb to self-doubt about the nation's goodness and future prospects for greatness. But the foul mood didn't last. Ronald Reagan's 1980 campaign and style of governance injected a dose of sunny optimism back into the country. It shone even brighter when the economic boom that began in the third year of Reagan's presidency seemed to vindicate his faith in the country, as did the shocking end of the Cold War and sudden collapse of the Soviet Union soon afterwards.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Things are very different today.

Donald Trump's success at winning the Republican nomination is a powerful sign that the pessimism of the late 1970s has returned, albeit in darker, angrier form. Trump will almost certainly lose the election, but it's crucially important that his party devise a productive response to the black mood that birthed his campaign. Without such a response, the pessimism that pervades large portions of the Republican electorate will only deepen, moving in increasingly volatile, illiberal directions.

The drift toward pessimism has been apparent for several years — as the country endured the terrorist attacks of September 11, the inconclusive outcomes of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (and less clearly defined military interventions in Libya, Syria, and elsewhere), the incompetent response to Hurricane Katrina, the financial crisis and resulting bailouts, and significant expansion of government regulation at a time when faith in public institutions has been spiraling downward. The result is the slew of opinion polls showing an overwhelming majority convinced that the country is on the wrong track.

But unlike the pessimism of 40 years ago, today's darkness isn't equally dispersed throughout the country and between the major parties. This is primarily a pessimism of white Republicans, and especially white Republican men who have not graduated from college and who are either economically working class or middle class.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Because Trump's campaign has inspired an indeterminate number of loud-mouthed bigots to spew racist, anti-Semitic, and sexist venom on Twitter and at campaign rallies — and because of Trump's signature emphasis on sealing the borders and deporting undocumented immigrants — many have concluded that Trump's white-male admirers are motivated primarily by racism. But underlying the racism of some is a far more pervasive gloom about the future.

A recent Pew Research Center poll provides an important glimpse into this mindset. Perhaps the most shocking finding is that 52 percent of white respondents believe that life in the U.S. is worse for people like them than it was 50 years ago. (Only 33 percent of whites think life has gotten better for people like them over the same period.)

That's a surprisingly high number of dissatisfied voters, but it's nothing compared with the rate of dissatisfaction among Trump supporters, 81 percent of whom think that life in the U.S. is worse for people like them than it was in the mid-1960s. (Only 11 percent think that life has improved for people like them over the past half century.) Perhaps equally troubling is how starkly Hillary Clinton supporters diverge from this sullen outlook, with 59 percent of her backers holding that life has gotten better for them over the past 50 years.

Not surprisingly, the sharply divided views of the country extends into the future as well, with 68 percent of Trump supporters believing that life will get worse for them over the next generation. That compares with a nearly identical percentage (66 percent) of Clinton supporters who say that life in the future will either be better than or the same as today.

The GOP is becoming America's party of pessimism.

That's disconcerting for several reasons. For one thing, it means that large numbers of Americans believe they and their children can no longer thrive in the United States. That signals the rise of widespread hopelessness, which can easily become a self-fulfilling prophesy, as individuals and families stop striving (and making sacrifices) for a better future they're convinced is unattainable. That's a recipe for (further) economic stagnation, psychological depression, and the social pathologies that tend to accompany both.

But the political consequences could be even more ominous.

People who believe their lives are likely to get worse over time tend not to accept that fate complacently. On the contrary, pessimists often end up searching for and tempted by would-be saviors — individuals or movements who promise to break the pattern of decline. But because the status quo is implicated in the decline, the individuals or movements that inspire the greatest hope for improvement are the often ones who threaten to do the most damage to the established order of things in preparation for a miraculous leap into a new and dramatically better world. Pessimism is a potent incubator of political radicalism.

We've gotten a taste of such radicalism in Trump's vaguely defined promise to "Make America Great Again," which has been attached to proposals for radical shifts in immigration, trade, and foreign policy. Whether Trump loses in November or wins and then fails (as he almost certainly would) to make noticeable improvements in the lives of his pessimistic voters, those voters are bound to grow more pessimistic, and hence more radical, in future elections.

Our best hope of avoiding that radicalizing fate is for Republican candidates to finally start listening to the most pessimistic members of their party's base and begin formulating policies that might give them greater hope. (Hint: upper income tax cuts, open borders, and endless wars in the Middle East aren't going to cut it. But neither is the panglossian optimism to which many otherwise thoughtful liberals, and a fair number of neoconservatives, are prone.)

If the effort fails, or it's never attempted, Trump may well come to be viewed as merely the first, and most benign, figure to emerge from a rising pessimistic right. And then the rest of us may end up wondering whether pessimism about the nation's future just might be a sensible position after all.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The best dark romance books to gingerly embrace right now

The best dark romance books to gingerly embrace right nowThe Week Recommends Steamy romances with a dark twist are gaining popularity with readers

-

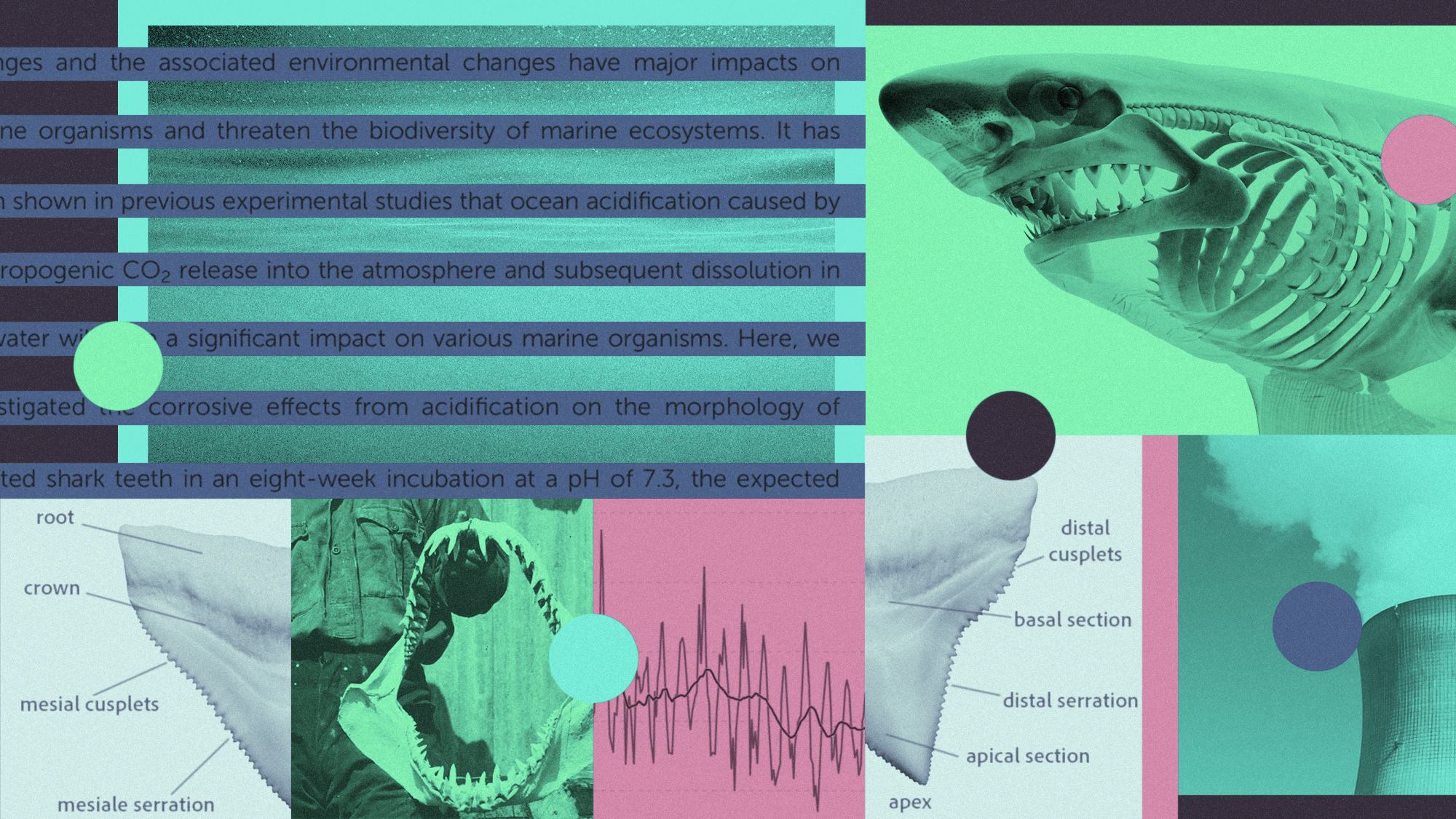

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ a study’s author said

-

6 exquisite homes for skiers

6 exquisite homes for skiersFeature Featuring a Scandinavian-style retreat in Southern California and a Utah abode with a designated ski room

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred