The worrisome rise of neoskepticism

This ideology threatens the fight against climate change

An increasing number of Americans now acknowledge that climate change exists and is exacerbated by humans. But, even as the uproar from climate deniers diminishes into a whisper, a fresh and potentially detrimental ideology is taking hold: neoskepticism.

Neoskeptics aren't deniers. They recognize the prevalence and cause of climate change, but still, they advocate against large-scale efforts to stop it. Why? Some believe there's too much uncertainty surrounding the issue. Others think stopping climate change would simply be too costly. But whatever their reasons, this increasingly popular perspective has started to worry scientists. With this summer seeing the warmest global temperatures in NASA's records, neoskepticism could lead to "policy paralysis," says Paul Stern, co-author of a recent report about the ideology in the journal Science. By waiting for more certainty on the threat of climate change or more evidence of its catastrophic nature, the country is "postponing decisions that need to be made," he says.

Neoskeptics have been increasingly vocal in the public sphere over the last two years. In 2014, American climatologist Judith Curry wrote in The Wall Street Journal that the need to reduce carbon-dioxide emissions is less urgent than many assume. In the same publication, Steven Koonin, the director of the Center for Urban Science and Progress at New York University, argued that we should invest in "accelerating the development of low-emissions technologies and in cost-effective energy-efficiency measures," but not much else, since "we are very far from the knowledge needed to make good climate policy."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But uncertainty isn't an excuse for inaction. There is some degree of uncertainty in everything, says Stern, who also serves as a principal staff officer at the National Research Council. He compares the Earth's situation to a human medical condition that can only be fixed with a long, costly procedure. Doctors can't say with 100 percent certainty that the condition will kill the patient — or in this case, the planet — so the decision of whether or not to treat the problem must be based on the information available, Stern says.

So what's to be done? Stern and his co-authors argue that scientists need to help the public feel more comfortable with making large-scale policy decisions on climate change. Up to this point, the focus has been mainly on demonstrating that climate change is happening and that it's caused by human activity. It's important now to move the issue forward by providing the public with information on how bad the problem is as well as a comparison of the costs and benefits of fighting versus doing nothing.

Overall, the ideological shift about climate change in the U.S. is palpable, and can be seen in the recent large-scale global warming rallies and California's recent commitment to fight climate change. In 2016, the percentage of Republicans and Democrats who said they believe the effects of global warming have started is the highest it's been since 2009, according to an upcoming article to be published this month in the science magazine Environment.

So maybe neoskepticism is a natural next ideological step for those who are transitioning away from denying or questioning climate change's existence, Stern and his colleagues speculate. It's common for "defenders of business as usual" to start by questioning whether an issue exists at all, and then question "the magnitude of the risks and assert that reducing them has more costs than benefits." Indeed, some climate experts consider the popularity of neoskepticism an encouraging sign. "As the policy debate becomes a question of how to tackle climate change rather than if we should act, it's a good thing," says Angela Anderson, climate and energy program director of the scientific organization Union of Concerned Scientists.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The danger is that we'll wait too long to take large-scale action to combat climate change, and a fix will no longer be possible, says Jamie Henn, co-founder of the environmental organization 350.org. Over the past century, the planet's average temperature has increased by 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit, and is expected to rise as much as 8.6 degrees over the next 100 years, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. If the planet's temperature gets warm enough to thaw a large portion of the Arctic's permafrost, it could cause carbon to be released into the atmosphere, resulting in a drastic uptick in the planet's temperature.

"The broad trend is going in the right direction," Henn says. "The question is: Can it happen fast enough?"

Hallie Golden is a freelance journalist in Salt Lake City. Her articles have been published in such places as The New York Times, The Economist, and The Atlantic. She previously worked as a reporter for The Associated Press.

-

A luxury walking tour in Western Australia

A luxury walking tour in Western AustraliaThe Week Recommends Walk through an ‘ancient forest’ and listen to the ‘gentle hushing’ of the upper canopy

-

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers want

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers wantThe Explainer White supremacism has a new face in the US: a clean-cut 27-year-old with a vast social media following

-

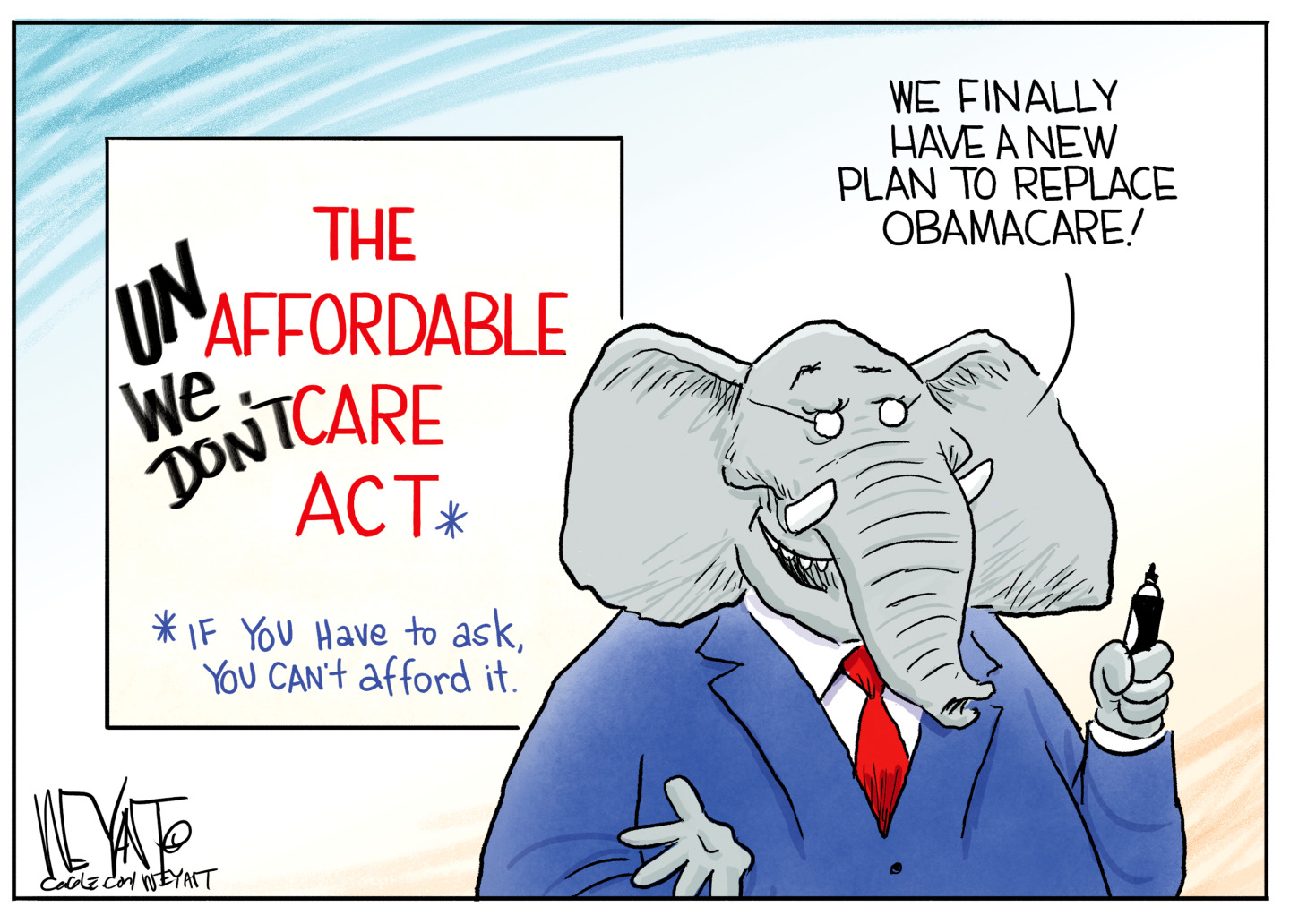

5 highly amusing cartoons about rising health insurance premiums

5 highly amusing cartoons about rising health insurance premiumsCartoon Artists take on the ACA, Christmas road hazards, and more

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration