This hacked Clinton campaign email shows why 'serious' people just don't get climate change

Centrists instinctively balk at the radicalism necessary to fight climate change

One of the biggest problems with climate change is the sheer scale of the changes necessary to tackle it. A climate policy that is equal to the challenge — that is, one which would ratchet down greenhouse gas emissions fast enough to prevent catastrophic warming — requires spectacular overhauls to practically every sector of society, done as fast as possible. While America and the world have been making strides to deal with climate change, so far the efforts are halting and pitifully inadequate.

Most people instinctively resist conclusions like this. It sounds extreme, which is generally an indicator of wrongness. But sometimes extreme problems require extreme solutions. A failure to appreciate the radical implications of climate change is a political error of the first order.

Unfortunately, it's an error that is far from unusual — particularly among serious politics people. In the WikiLeaks email hacks, one anodyne but telling conversation happened between Clinton campaign chair John Podesta and two Clinton aides, Josh Schwerin and Jake Sullivan.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Back in June of 2015, Schwerin was considering angles of attack against Martin O'Malley (recall that the great Sanders insurgency had not yet gained much steam at that point). O'Malley had just published an article calling for 100 percent renewable energy by 2050. Schwerin wrote that "zeroing out fossil fuels within 35 years seems unrealistic," and that he was considering trying to get something published on how "this may be well-intentioned but it's not a serious proposal."

Podesta, to his great credit, does have a firm grasp on climate policy. He correctly replied that O'Malley's timetable was roughly accurate. This prompted a response from Sullivan, who was incredulous: "But he is saying zero fossil fuels, period, isn't he? Transport, buildings, and energy? … John — you think that is realistic?" Podesta responded that while it will be tricky to get all the oil out, the Clinton campaign "wouldn't want to fight him on that."

This exchange is an excellent demonstration of how tremendously dangerous centrist instincts are when it comes to climate change.

One good way of inferring someone's political priorities is by examining what they assume cannot be changed — what they hold constant in a political calculation. The centrist mindset generally assumes that politics cannot be changed very fast, and that the best policy is towards the middle of the political spectrum. So if a centrist doesn't have a good grip on climate science and policy, then there will always be a temptation to bend the scientific implications rather than the politics. That's how you get a political staffer seeing something that sounds radical and simply assuming it can't be correct — and Sullivan and Schwerin are far from alone in this reaction.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Part of this, no doubt, can be chalked up to the unusual character of climate change. While the science is extremely solid, and the logic of necessary climate policy is straightforward, the chain of reasoning is arid and distant from everyday life.

Compare climate policy to a somewhat similar situation: a full-blown war. The threat of, say, Nazi armies invading the United States was once far more palpable and immediately terrifying than some technical-sounding climate problem whose worst effects won't be felt until long after everyone alive today is dead. Additionally, hyper-aggressive policy action to confront a foreign attacker is historically familiar. Nationalizing the steel industry to crank out war materiel at warp speed slots directly into a cultural tradition that is thousands of years old. A hyper-aggressive raft of policy to wring fossil fuels out of the economy sounds strange — and is largely untested.

But the threat of climate change is no less than that of a major war. It's so easy to look past, in fact, that sometimes high-level staffers working for a liberal Democratic presidential campaign have basically no understanding of it — the most important political problem in the world.

Fortunately, Podesta has done his homework, and with any luck he'll be able to convince Hillary Clinton, if she has not come around already. But until the political class writ large stops using "small-bore" as a marker of seriousness, advocating for climate policy will remain an uphill struggle.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

How AI chatbots are ending marriages

How AI chatbots are ending marriagesUnder The Radar When one partner forms an intimate bond with AI it can all end in tears

-

Political cartoons for November 27

Political cartoons for November 27Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include giving thanks, speaking American, and more

-

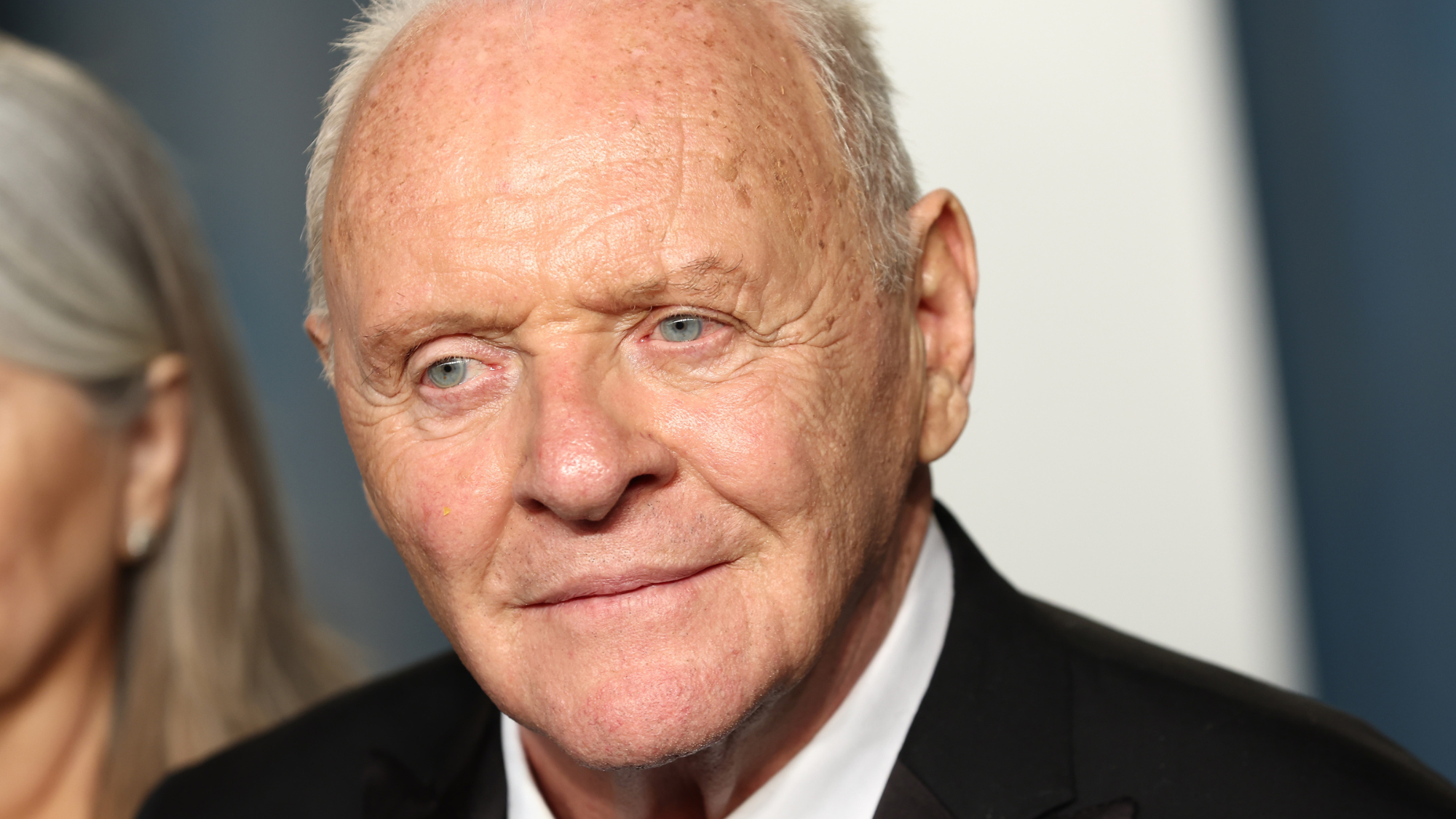

We Did OK, Kid: Anthony Hopkins’ candid memoir is a ‘page-turner’

We Did OK, Kid: Anthony Hopkins’ candid memoir is a ‘page-turner’The Week Recommends The 87-year-old recounts his journey from ‘hopeless’ student to Oscar-winning actor

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration