This evangelical leader gave the most important speech about the religious right in the age of Trump

In the most searing line, he concludes: "The religious right turns out to be the people the religious right warned us about"

Donald Trump is a master of humiliation. Mostly he humiliates himself, but he has also humiliated countless people and entities over the course of his life and presidential campaign. If you had to draw up a list, near the top would have to be the religious right.

To say that some of the religious right's top leaders have beclowned themselves by embracing Donald Trump is an understatement. It's hard to know even where to begin. Donald Trump practices almost every kind of immorality forbidden by the Bible — and brags about it. He claims to be a Christian, but seems to know nothing about Christianity or show any interest in it. He has said several times that he has never asked God for forgiveness for anything, even though asking God for forgiveness is just about the most basic qualifier of a Christian. Oh, and Donald Trump is temperamentally unfit to be president of the United States.

And yet this is the man many on the religious right embrace — even though it has previously denounced political figures as beyond the pale for lesser slights. To say that this is intellectual and moral bankruptcy is an understatement.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Enter Russell Moore. He may not (yet?) be a household name like a Jerry Falwell Jr., but he is an important man in the religious right. He's the president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, the public policy arm of the Southern Baptist Convention. In other word, he's the "Mr. Politics" of the largest Protestant denomination in the U.S., one that is evangelical, conservative, and largely based in the Bible Belt. If anything qualifies as a leader of the religious right, this is it.

This week, Moore was invited to give the Erasmus Lecture, a prominent lecture given by the intellectual Christian magazine First Things (a previous honoree was a clergyman named Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, better known today as Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI). And boy, is it a doozy. Moore basically called out the religious right — and particularly his own section of the religious right, conservative, white evangelical Protestantism — for all the flaws that are so glaring to those outside it.

Moore's speech begins by recounting a spiritual crisis he underwent as a teenager. He had been brought up as an evangelical in the heart of the Bible Belt. But as he grew older he became disenchanted by the hypocrisy and vacuousness that was already apparent then (as it is apparent, in various forms and guises, in every religious community, as Jesus himself pointed out relentlessly), whether it took the form of "voter guides" that seemed eerily to parrot Republican National Committee talking points, except with Bible proof texts attached, or pastors denouncing adultery from the pulpit while honoring benefactors who were notorious adulterers, or literalistic interpretations of Biblical prophecies, always applied to the political controversies of the day. Providentially, Moore found his way to a deeper, more grounded form of Christianity, instead of drifting away from the faith as so many in a similar situation have. But that experience certainly forms the backdrop of his speech.

Moore then goes on to zing the religious right for its hypocrisy and moral bankruptcy. While disagreeing with them, he respects those Christians who are disgusted by Trump, but will hold their nose and pull the lever for him as the lesser of two evils. But, he goes on to note, many religious right leaders have not made that argument, but instead embraced Donald Trump and found excuses for his pandering to white nationalism or bragging about assaulting women. He points out that the same crowd — indeed, in some cases, the very same people or institutions — was calling for figures like Bill Clinton and Rudy Giuliani to resign over their own infidelities, because a basic moral standard has to be upheld for public figures. They're the ones who made the argument that political office requires not just having the right positions on issues of public policy, but also meeting a certain threshold of moral character. Yet here we are.

In the most searing line of the speech, Moore concludes: "The religious right turns out to be the people the religious right warned us about."

He also points out that this sort of behavior is killing the religious right. He didn't put it that starkly, but it's pretty clear that everyone outside the echo chamber can see what phonies they are.

But there's a bigger problem for the religious right, as Moore notes, which is that on most issues, mainstream American society has moved away from conservative Christianity. The old-line religious right could talk of a "Moral Majority" because it was true that on a set of basic moral issues, most Americans, while not Bible-thumping evangelicals or Aquinas-quoting traditional Catholics, were closer to traditional Christian views than to the progressive left. Which, if your basic duty as a religion is to evangelize people, makes it all the more important to (again, saying essentially the same thing as Moore in less guarded language) not look like money-grubbing, power-hungry, hypocritical sycophants and nincompoops.

The religious right now stands bankrupt. The question is, to pursue the bankruptcy metaphor further, is it a chapter 7 bankruptcy or a chapter 11? Do we shut the whole thing down, or is it possible to come out of the other side healthier, after some painful — no doubt very painful — restructuring?

"What's at stake here is not just credibility, it's also the question of whether religious conservatives even want a future," Moore says.

Moore sees rays of hope for the religious right nonetheless. He points out that, contrary to many predictions, the young have not deserted conservative Christianity. Young people are "packing into orthodox and confessional universities and seminaries" and planting churches left and right, Moore notes. And while those young people may care more than their elders about traditionally progressive issues like racial or environmental justice, it is by no means because they have become liberal. In most cases, they are just as conservative, both theologically and morally, as their forebears.

What's more, while American millennials have drifted very far from Christianity in many respects, they are "conservative" in others. The millennial generation is no less pro-life than the previous generation. Importantly, tantalizingly, it is also much more anti-divorce than the previous generation, as being the one that lived through the divorce waves of previous generations.

"The evangelicals who are the center of evangelical vitality are also the least likely to be concerned with politics. Not because they're liberal, but because they want to keep a priority on the Gospel and the mission that they do not wish to lose," Moore says. This is a sign of weariness with the excesses of the religious right, but also a sign of hope, if it is not pushed too far in the opposite direction.

There's another thing that the young generation understands, Moore says. Today, many in the religious right and the Bible Belt understand "evangelical Christianity" to mean white evangelical Christianity. But the future of the church is global. In evangelicalism, as well as Catholicism for that matter, the energy in the church is global. By becoming enmeshed with, if not white identity politics per se, then certainly the white culture of the Bible Belt, the religious right has cut itself off from a key source of vitality within Christianity, and has overlooked — if not been downright hostile to — causes that should matter to Christians like racial justice and reconciliation.

So, there are seeds of hope, perhaps. What's the way out?

In perhaps the most important phrase of the speech, Moore says: "One of the assumptions of some in the old religious right is that the church is formed well enough theologically and simply needs to be mobilized politically."

Most Christians simply don't know what they believe and why, and that is killing Christianity. Jacob Lupfer, a scholar of American Christianity, has noticed that within evangelical Christianity, the pro- versus anti-Trump split has come down along lines that are not so much political, or even theological per se, but confessional. "Generic evangelicals or cultural/nominal Protestants go for Trump. Confessional evangelicals are theologically primed to resist him." By confessional, he means those believers, churches, and institutions that stress preaching and adhering to specific historic Christian creeds. (This also probably explains why Mormons and Catholics, including conservative Catholics, have also tended to be outliers in their rejection of Trump.)

In other words, Christians have made such a mess of the religious right largely because they've lost sight of what it means to be Christian.

Moore is not calling for a retreat of Christians from politics. The Christian faith calls on believers to regard themselves as strangers in a strange land, and citizens of Heaven first and Earth second, but that "second" matters. They need to serve their fellow men, including through public service and advocacy. Political organizing is good, Moore exclaims at one point. What's more, it's not just that Christians need politics, it's that America needs conservative Christians. As Trump shows, without conservative Christianity, the right will not simply go away, as some progressives might hope, it will become more like the ethno-nationalistic populist right of Europe, and more Nietzchean, Moore warns, rightly in my view.

But for Christians to stop shaming themselves in the public square, let alone start playing a constructive role, they must first become more grounded in their own faith. Christians are supposed to believe in divine providence, so I can only say: from Moore's mouth to God's ears.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

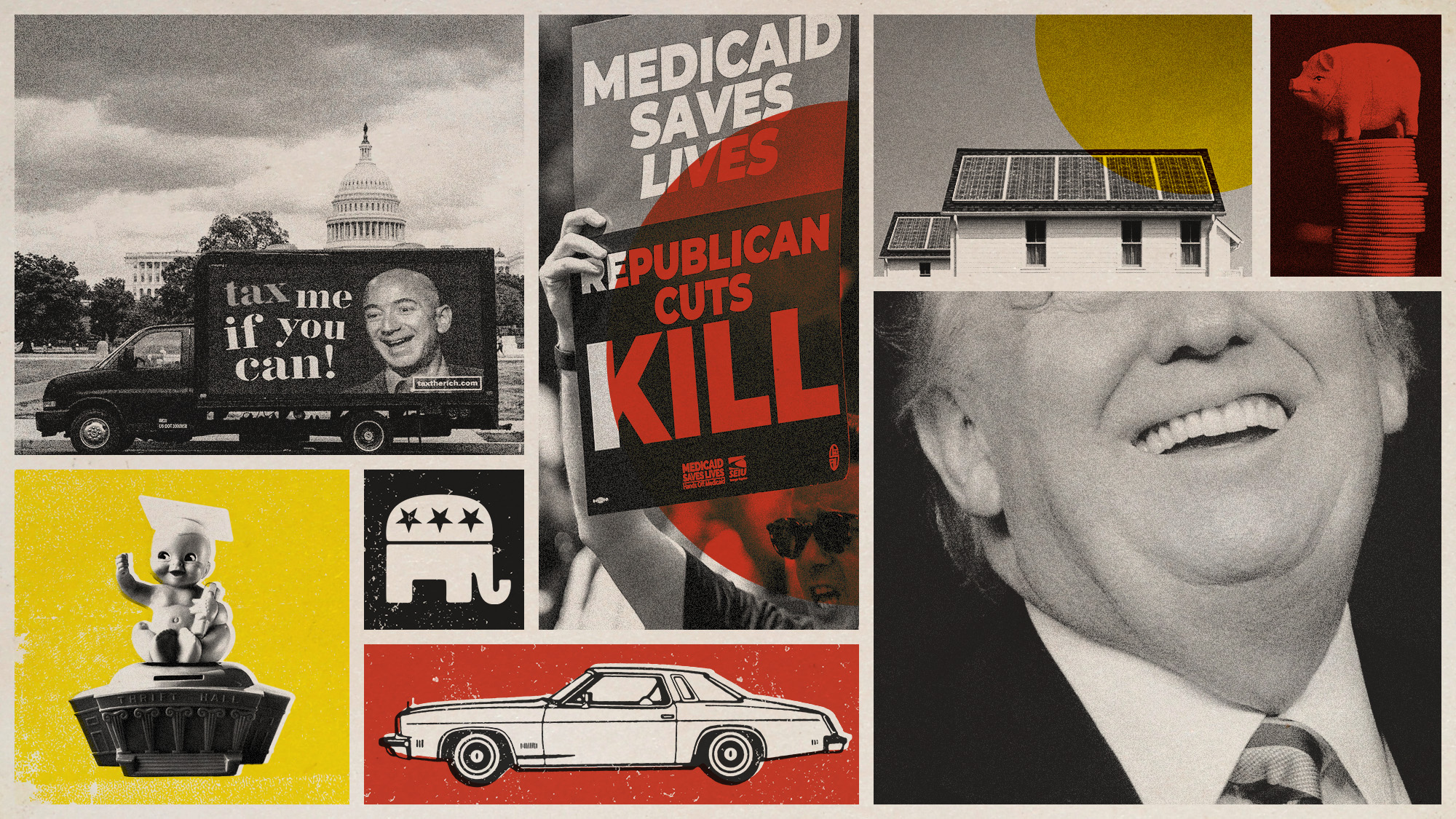

How will Trump's megabill affect you?

How will Trump's megabill affect you?Today's Big Question Republicans have passed the 'big, beautiful bill' through Congress

-

Scientists are the latest 'refugees'

Scientists are the latest 'refugees'In the spotlight Brain drain to brain gain

-

5 dreamy books to dive into this July

5 dreamy books to dive into this JulyThe Week Recommends A 'politically charged' collection of essays, historical fiction goes sci-fi and more

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

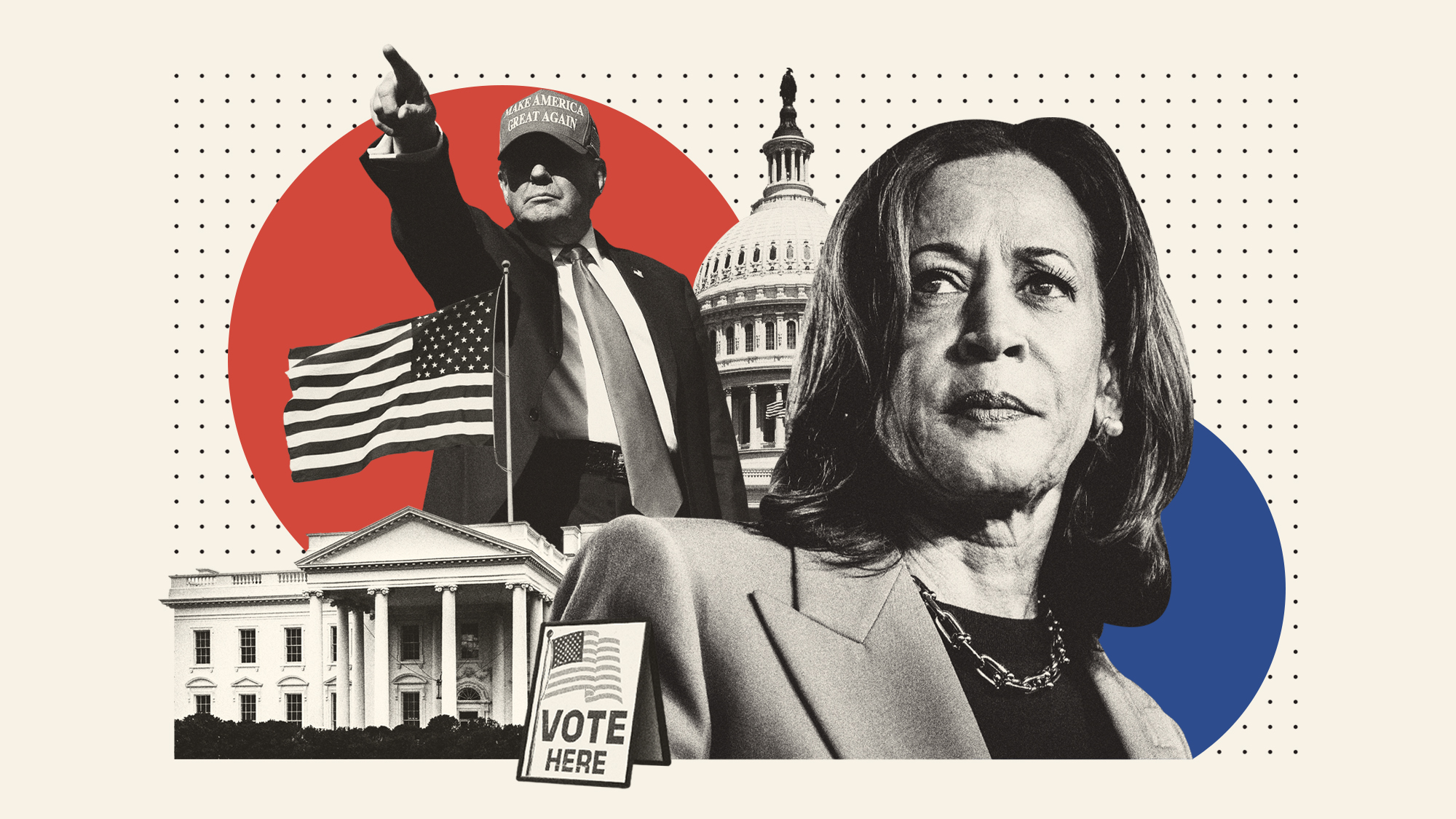

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?