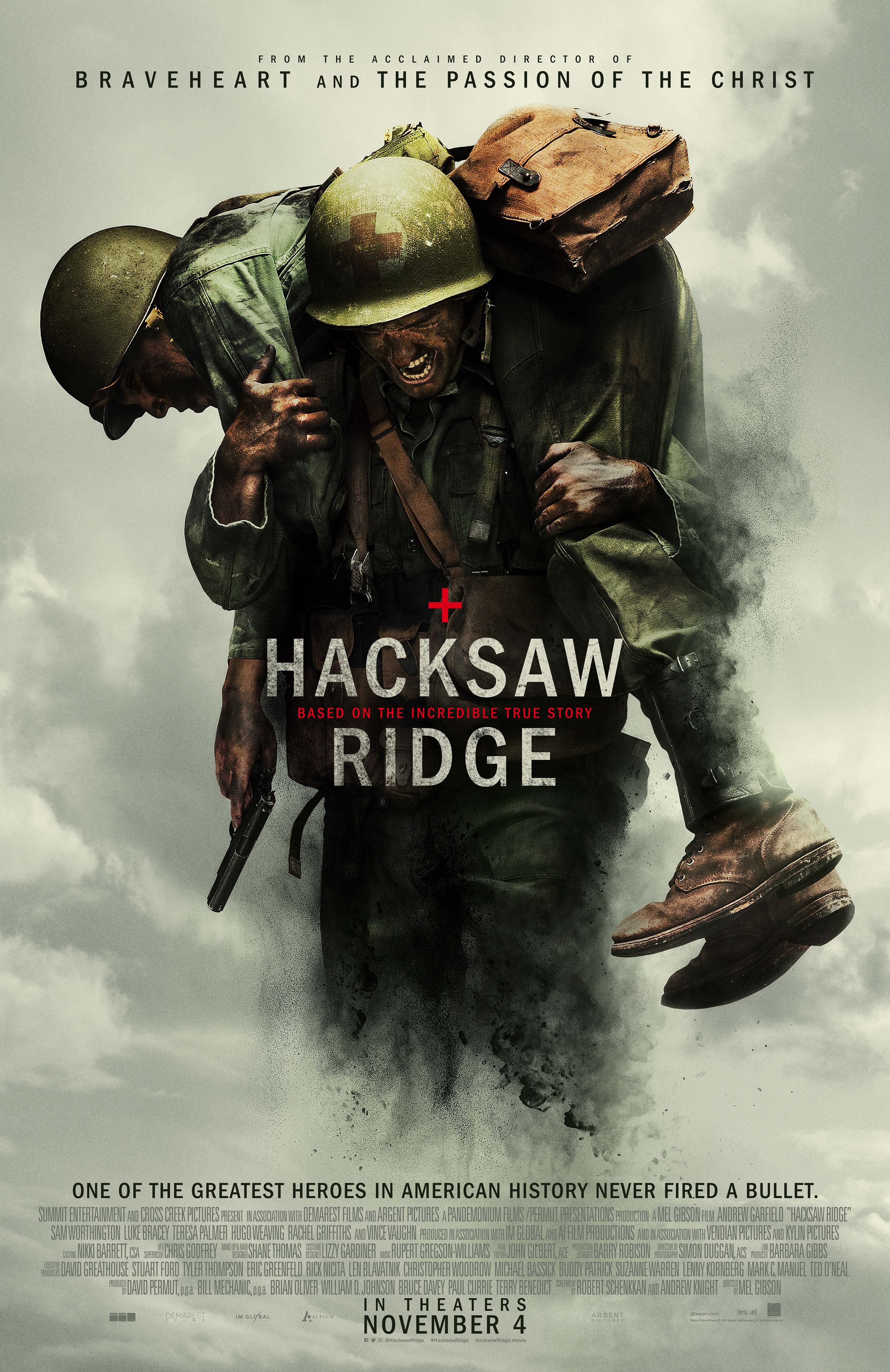

Mel Gibson just made the most violent American film of the year. And it's sublime.

In Hacksaw Ridge, Gibson once again reveals his heart of darkness

"Separate the art from the artist." That old axiom, intended to exonerate people who want to discuss art created by morally dubious artists (heaven forbid!), doesn't really apply to Mel Gibson the way it does Woody Allen or Roman Polanski. Gibson has been cast off into Hollywood Purgatory for a decade, following his notorious drunken anti-Semitic diatribe in 2006 and a series of increasingly worrisome psycho-zealot revelations in subsequent years. Allen and Polanski, however, remain as prolific as ever, even winning Oscars despite their well-known transgressions, making Gibson a curious exception to Hollywood's ethical leniency.

Why is Gibson different? One key reason is that his demons haunt his films. Art and artist are not easily divisible. To separate the art from the artist here is to exorcize the art's troubled soul.

Hacksaw Ridge, Gibson's first film in 10 years, might revive his career. It extrapolates the filmmaker's dogged beliefs as sacred truth while acting as commentary on the passions, the agonies and ecstasies, that compel him. Desmond Doss (genial Andrew Garfield, spittling a southern drawl out of pursed lips), the son of a belligerent, abusive drunkard WWI veteran (Hugo Weaving), is a devout Christian and conscientious objector who enlists in the army during World War II — despite his refusal to touch a weapon. His pacifism, derided as cowardice, pisses off his petulant/patriotic comrades, many of whom have thick New Yawk accents to further emphasize Doss' isolation. But the gangly, God-loving Doss ends up saving the lives of 75 soldiers at Okinawa, and is heralded as a hero by the men who previously called him craven.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The film can generously be interpreted as a self-vivisection for Gibson, with its pacifist Christian hero standing steadfast against persecution and the inexorable impetus of violence enveloping him, or more skeptically be dismissed as more moribund indulgence from the man who finds amusement in the destruction of the human body (if not spirit). Hacksaw is split into two sections of fiercely different styles. The first hour is a Hollywood melodrama, real fluffy stuff rife with 1940s-derived piety and platitudes that feel like a Frank Capraesque take on God's Not Dead — you can almost picture pre-War Jimmy Stewart playing Doss, so unreservedly divine is his determination and utter lack of flaws. The second half is a relentless barrage of graphic violence crafted with a distressing level of proficiency, as if Gibson is vying to be the Terrence Malick of massacres — human bodies torn asunder by bullets and bombs, set aflame and tumbling like broken gymnasts towards the camera in revolting high-def digital photography, innards strewn across the dirt in expressionist splatters and sonorous death wails echoing. It is, unequivocally, the most violent American film of the year, morally confusing with its us-vs-them dichotomy ("us" being Americans, "them" being the Japanese), yet somehow sort of sublime.

Hacksaw Ridge is so loud and brutal, you may start to beg, to pray, that each brief respite from the carnage will be the end. Gibson shows no mercy. It was shot by Simon Duggan, who also shot 300: Rise of an Empire and The Great Gatsby, and the marriage of Gibson's pitilessness with Duggan's decadence renders the grotesqueries of war in graceful detail. Every death is blocked with exquisite, balletic precision, which will invariably draw comparisons to Saving Private Ryan.

Gibson's religious convictions are as deeply entrenched as the soldiers burrowed into dirt troughs, and his depiction of the non-Christian Japanese as hellspawn savages is, to say the least, upsetting. You can read it as Gibson taking the perspective of the American soldiers, who spew ignorant hatred casually, but that might be a generosity too far. The sole moment of empathy allowed to the Japanese is during a juxtaposition of two faiths: Doss mews for his bible, as he's being carried Christ-like through the battle-ravaged ruins of Okinawa, while a forlorn Japanese officer commits seppuku in dramatic slow-motion in the darkened catacombs below. It might be the movie's act of contrition, a moment of penance and epiphany; Gibson might be trying to depict the similarities between faiths, the ties that bind all believers, as each soldier (the victor and the defeated) clings to unwavering credence in what could be their final fleeting moments of life.

Or Gibson might just be saying, "See! Christianity is the one true religion, you heathens!" It's debatable.

Hacksaw Ridge claims to be "A true story," but it's more like a story of truthiness, keeping with the spirit of Gibson's other historical epics. (One character reminds Doss that the Bible is metaphorical, not literal, and you can't help but wonder if Gibson views history with the same insouciance.) Braveheart's digressions from reality are too many to list, and in The Passion of the Christ, Jesus (Jim Cavaziel, looking like a supermodel) spills more blood than any human body could ever possibly contain. The sublime Mesoamerican nightmare Apocalypto, Gibson's best film, conjures up a long-dead civilization — or, rather, invents one from that torture chamber imagination of his. Gibson stages a world of entangled vines and looming seraphic structures erected in the mire of a green inferno, replete with decapitated heads bouncing down steps and brains battered with bludgeons and stones. Again, he juxtaposes people with kindred beliefs, and how faith can be interpreted variously and used for nefarious means, or can help one survive in times of trial; again, he treats the human body as disposable, a husk when expunged of spirit.

This ethical and philosophical quandary, of violence begetting enlightenment, is the soul of Gibson's artistry. His is a nihilistic, cruel worldview, yet hope pervades his films. Gibson genuinely believes in the omnipotent sovereignty of Christ Almighty, and is what you could call an Old Testament filmmaker, conflating Hollywood classicism with brazen brutality. With Hacksaw, he crafts an epic of bodies blown to bits, then gives us an earnest, unironic image of a pacifist hero ascending towards the azure heavens. Gibson turns the other cheek, and then he takes an eye.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Greg Cwik is a writer and editor. His work appears at Vulture, Playboy, Entertainment Weekly, The Believer, The AV Club, and other good places.

-

'Cordial Conversation' cocktail recipe

'Cordial Conversation' cocktail recipeThe Week Recommends This multi-layered cocktail features an appealing combination of flavours including jasmine tea and watermelon syrup

By Rebekah Evans, The Week UK Published

-

Europe's most beautiful campsites

Europe's most beautiful campsitesThe Week Recommends From wild camping to luxury glamping, these magnificent spots are the perfect setting for nature-filled break

By Irenie Forshaw, The Week UK Published

-

The UK's first baby born to woman with womb transplant

The UK's first baby born to woman with womb transplantThe Explainer 'Astonishing' medical breakthrough, the culmination of 25 years of research, could pave the way for more procedures to combat uterine infertility

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

By Theara Coleman Published

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

By Jeva Lange Published

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

By Jeva Lange Last updated

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

By Brendan Morrow Published

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

By Jeva Lange Last updated

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

By Jeva Lange Published

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

By Jeva Lange Published

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.

By Jeva Lange Published